[This blog post contains the podcast host and the interviewee’s personal opinions and perspectives. These views are not intended to represent the official policies or positions of The Steve Laube Agency, or any other affiliated group.]

Christianity has always been under attack. The current weapon of choice is “deconstruction.”

Recent generations that were raised on pornography now reject Christian morality and then deconstruct their faith altogether. As a Christian writer in the 21st century, you’re not fighting a theological battle over truth but an emotional battle over morality. Before you dismiss this conclusion, let me explain.

Jesus said, “You’ll be hated for my name’s sake. But the one who endures to the end will be saved” (Matthew 10:22).

The apostle Peter tells us,

Even if you should suffer for righteousness’ sake, you will be blessed. Have no fear of them, nor be troubled, but in your hearts, honor Christ the Lord as holy, always being prepared to make a defense to anyone who asks you for the reason for the hope that is in you. Yet do so with gentleness and respect, having a good conscience, so that when you are slandered, those who revile your good behavior in Christ may be put to shame” (1 Peter 3:14-16).

This verse is the foundation of a Christian practice called apologetics. It comes from the Greek word apologia, which means defense. Picture a Greek hoplite with a massive bronze shield.

The world will always attack Christianity, and we are called to defend it by giving a reason for our hope. But the nature of that defense changes with the nature of the attacks.

In ancient times, the Romans attacked Christianity for being atheistic. They said Christians denied the Roman gods and didn’t believe that gods existed.

A thousand years later, Muslims attacked Christianity for being polytheistic because they said Christians worshiped three gods.

Christian defenders in Alexandria, Egypt, had to defend against a very different attack from the Romans in 200 than they did from the Muslims in 1200.

To give a good defense for the faith, you must understand the question you’re being asked.

In the 20th century, apologetics answered critiques from scientists and atheists:

- Is Christianity true?

- Can the Bible be trusted?

- How do you explain miracles?

- Did Jesus really rise from the grave?

Many Christian authors are still answering these old questions.

People are asking different questions now.

Modern vs. Postmodern Thinking

In the last few decades, the world has radically shifted from a modern world ruled by science to a postmodern world ruled by emotion.

It turns out there’s a cure for atheism, and it’s called magic mushrooms (psilocybin). Magic mushrooms won’t make people Christians, but they do cause spiritual experiences that make people doubt their atheistic certainty.

There are no atheists in foxholes or on acid trips.

Science has been losing credibility for a long time. Things came to a head in recent years with the lies surrounding COVID, climate change, and the big replication crisis that has infected all of science.

Public perception has shifted. Scientists were once viewed as lab coat-wearing heroes; they’re now viewed as fedora-wearing cowardly liars.

Postmodern View

In the postmodern view, science isn’t the truth. Science is whatever the powerful want it to be. For example, now that powerful people need electricity to power AI, no one seems quite so concerned about carbon anymore.

Postmodernism is very cynical. It rejects objective truth. Postmoderns don’t care if Christianity is true in a scientific sense. They don’t care if it could win in a court of law. Nor do they care if Christianity could win a debate because they have their own truth. They believe that happiness comes from standing in your own truth.

All of the truth-claims of 20th-century style apologists giving Case for Christ or presenting Evidence That Demands a Verdict can be dismissed with a wave of the hand and a dismissive “That’s your truth.” It’s very disarming for Christians wanting to have a modern debate with a postmodern person who doesn’t care if something’s true or not.

Meanwhile, the postmoderns grumble that Christians are not listening to the questions that they’re actually asking.

Modern View

Moderns struggled with biblical claims about miracles and the supernatural elements of Christianity. C.S. Lewis was seen as incredibly courageous in his day for writing The Screwtape Letters and admitting that he believed demons were real. Moderns valued logic, and a single logical inconsistency made them doubt everything.

Postmoderns, on the other hand, live in a spiritual world full of inconsistencies and incongruities. They’re far more aware of the spiritual world than moderns, who often strictly reject the existence of angels and demons. Postmoderns don’t deny angels and demons; they just switch them up.

However, postmoderns do object to Christian morality.

In this new age, Christians must answer questions that are moral and political.

People who leave the faith often do so because they start rejecting Christian morality generally, then the Christian sexual ethic specifically. Only after they reject Christian morality do they later reject Christian theology. Postmoderns don’t understand why Christians believe that homosexuality is wrong. If two homosexuals are consenting adults, why is it wrong?

The generation raised on pornography rejects the Christian moral system, and then they deconstruct their faith altogether.

Current Christian apologists must answer different questions from those their predecessors had to answer. Today, people are asking:

- Is the God of the Old Testament good?

- Why should I adopt the Bible’s moral code?

- Why does Christianity say homosexual acts are a sin against God?

- Why does the Bible treat men and women differently?

- Why do I need to submit to a religion at all?

- Can’t I just be spiritual and not religious?

Two Incompatible Approaches

One apologetic approach that the church has tried in the last few decades is to join the postmodern rejection of the Christian sexual ethic. These postmodern Christians would say there’s nothing morally wrong with homosexuality, and there’s no difference between men and women.

But this approach does not defend the faith.

Churches that reject the Christian sexual ethic rapidly wither and fade. The PCUSA, Episcopal Church, and United Methodist churches are shells of their former selves, with far fewer people in attendance. If you visit a service today, you’ll see that its sanctuaries lack the young people it changed its theology to accommodate. In fact, the PCUSA is so anemic that they just ended 150 years of missionary activities and laid off most of their mission staff.

Interestingly, thriving churches are those with the clearest moral clarity. Traditional Catholics, conservative evangelicals, and conservative Orthodox churches are thriving.

I personally visited a conservative Catholic church with a friend, and there was not enough room for everyone to sit. The usher spent half the service trying to squeeze more folks into the packed pews and turning people away who were waiting in line for a place to sit.

This church held seven services that weekend, and two of them were in Latin. And the Latin services were popular! I was older than the average person there, and it was the first time I felt old at a church service.

Apparently, not allowing women to serve as priests didn’t have the impact on attendance that we were led to believe.

A Different Path to Faith

Now, I’m not pretending to know a lot about Catholicism, but I have noticed that young men are flocking to traditional conservative churches at record rates. Often, they adopt the moral ethic of Christianity after hearing from secular teachers like Jordan Peterson, Jewish teachers like Ben Shapiro, and, to a lesser degree, Joe Rogan. These men don’t claim to be Christians, but they all have moral clarity.

Once young men start listening to Jordan Peterson and adopting this “new” biblical moral system, they start putting their lives in order, which means attending church. As they attend church, they begin to understand the theological elements of Christianity.

This is the opposite path that moderns took a generation ago. Modern Christians embraced the theological and spiritual side of Christianity first, and later embraced the Christian moral ethic.

For example, when Keith Green converted, he continued living with his girlfriend for a while. While reading the Bible, he realized that he was living in sin, so he married his girlfriend, Melody.

Postmodern young men, on the other hand, start listening to people like Jordan Peterson and start putting their lives in order first. They adopt Christian morality before they convert or start attending church. In their eyes, the Christian sexual ethic is one of the most appealing parts of the religion. It’s a feature, not a bug, as we would say in the tech world.

So here’s my thesis for this episode: 21st-century apologetics is not an intellectual argument over logos, but a moral disagreement over pathos. Or, to put it in English, it’s not a debate about truth; it’s about emotional resonance.

In the 21st Century, Apologetics Is Political

Apologetics in this new age is inherently political. When we’re afraid to address politics, we start losing the next generation.

For many young people, the first step away from faith is watching porn, the second step is rejecting the Christian sexual ethic, and the third step is voting for the Democratic Party. This process is so common we have a word for it. We call it “deconstruction.”

The fact that we need a word for this is very telling. In the 1980s this would have been called “backsliding”; but that term doesn’t work because it is not just that people are slipping into sin, it is that they are rejecting the very moral system that says that sin is evil.

Conversely, for other young people, the first step towards Christianity is listening to Jordan Peterson, forsaking porn, and voting for Trump. This starts the process of reconstruction that leads them ultimately to church, then to the actual gospel.

The Law does not save (2 Corinthians 3:6). Putting your life in order does not save you. But, as Ray Comfort would say, the Law does show us our need for Christ. As Paul points out in Galatians 3:24, “The law is our schoolmaster who brings us to Christ” (KJV).

Authors, here’s where you come in.

We can’t rely on non-Christian voices like Jordan Peterson to direct young people back to church. The fact that it’s working at all is divine providence. Christian authors must take a clear moral stance on the political issues of the day.

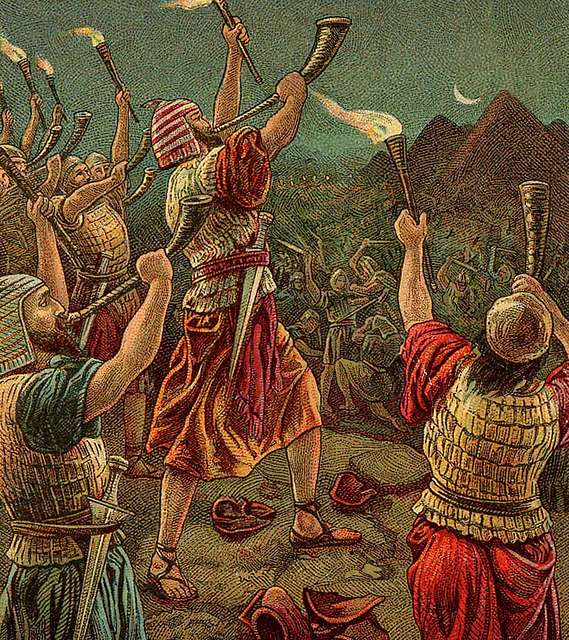

We need modern-day Elijahs who will challenge government authority.

We also need modern-day Elishas who are willing to integrate with government power.

Separation of church and state is not in the Bible, it’s not in the Constitution, and it’s not in the Declaration of Independence; but it is in the Baptist Faith and Message.

For years, Christian authors have avoided politics. That was a sensible approach when the political question of the day was whether the tax rate should be 30% or 35%.

But the political question today is very different. It’s moral. It’s spiritual.

One party advocates for killing babies and “transitioning” children. At the last political protest I attended, the Democrats were chanting, “Hail Satan,” and the Republicans were singing “Amazing Grace.” This is 21st-century politics.

Millions of young people follow Christian apologists like Charlie Kirk, who is willing to answer political questions and doesn’t shrink away from politics.

If you’re looking around your church wondering where the young people are, they’re out there looking for moral clarity.

Christians have been told for decades that church and state should be separate and that Christians should leave governing to pagans and atheists. We’ve been told that darkness is stronger than light and that if we try to bring light to politics, we will be made dirty, rather than the politics being made clean.

Now, this is a strong thesis that is probably making you uncomfortable, and it deserves a rebuttal.

So, I invited Chase Replogle, pastor, author, and host of the Pastor Writer podcast, to give a response.

Do Christian writers need a clear political stance in their writing and lives?

Chase: It’s a pleasure to join you again for an interesting conversation. Is there any more relevant conversation we could be having right now?

Thomas: This is the question of the day, and I’m curious to hear your thoughts.

Chase: I resonated with much of the history you recapped.

A few years ago, I picked up a book by Alan Noble called Disruptive Witness (affiliate link). He told a story about two friends who hadn’t seen each other in a while. One was explaining how they had come to faith and how they had come to believe in Jesus and the resurrection. This person was really trying to lead the other friend to what we would traditionally imagine as an evangelism moment.

At the end of the conversation, the second friend basically said, “That’s great. I should tell you about the CrossFit gym that I’ve joined. I’ve been finding many of those same things.”

Noble’s point was exactly the point you’re making. People are not so much looking for what we used to think of as truth as much as they are looking for their own experience of truth or the truth that works best for them.

This is a real danger for us as writers.

I have a friend who says the church is really good at answering the questions people asked 20 years ago. I feel that temptation as a writer too. It takes time for us to understand arguments and to form compelling arguments. Sometimes it can take so long that our answers lag behind the questions people are asking.

For a long time, we thought the big danger to the church was the New Atheism movement and that people were going to leave the church to become atheists. That is not what ended up happening.

People ended up leaving the church, as you articulated well, not because they were no longer spiritual, but because of their issues or perceived issues with Christians.

Francis Schaeffer wrote about the idea of how truth, capital-T Truth, a system of truth, had broken into what he called two stories of truth: a lower story of a house and a second story. On the bottom story were things like scientific facts. On the upper story were things like values, things that are meaningful.

We divided those two parts of the house. In other words, if I can scientifically prove something, it’s a fact. If not, then it’s a value that is open for personal expression, personal truth, and personal experience. That idea has led to a significant sacred-secular divide.

I feel this divide as a pastor. In sacred spaces, I’m allowed to talk, pray, and give input. In many secular spaces, that’s a job for scientists and politicians, not pastors.

We live in our perception of truth within those categories more than we may realize. Even scientific facts are becoming more related to value than actual facts. But we hold the higher truth to be those personal values, the things that work for us and seem right for us. Once something is put in that value category, it’s very hard to disagree with somebody.

A person pretty naturally says, “Well, I’m glad that truth works for you. This truth works for me.” We’re rarely able to have a conversation around what is actually true. It slips into emotions, as you put it.

Robert Bellah, a great sociologist, talks about emotivism, in which emotions and our experience of them now have become our arbiter of truth. So, if something makes me feel bad, it must therefore be morally bad. If something makes me feel good, it must therefore be morally good.

Increasingly, we’re using our sense of emotions and well-being as a guide for what is true and false. That makes it very hard to traditionally evangelize a person by talking about hell, the consequences of sin (both of which I believe in!). If those topics make a person feel uncomfortable or bad, they perceive it as something to avoid and as something that’s actually morally wrong. “You making me feel this way is morally wrong, even evil.” The shift has changed the dynamic of what it is to talk about truth and how we engage conversations around truth.

The Idol of Relevance

Thomas: Language is violence now. Saying something that makes somebody unhappy is seen as equal to striking them on the face. Moderns would say, “Sticks and stones may break my bones, but words will never hurt me.” The postmodern view is that words are more dangerous than sticks and stones.

Chase: This is a unique challenge for writers to navigate. I feel it myself, because most of the language and tools I have as a Christian come from that old world we grew up in and learned to think within. It’s not just that those tools are ineffective; they no longer lead to real engagement. As soon as I slip into those familiar ideas and words, most people respond with, “I’ve heard this all before, and it’s not interesting anymore.”

One way to approach the political side of this is to recognize that the church has long been obsessed with the idea of being relevant.

There was a major church growth movement, especially when I was in seminary, where everything centered around relevance:

- How do you speak the language people are speaking?

- How do you dress like them?

- How do you play music that fits their lifestyle?

The big mistake we made was that we became so focused on being relevant that many of us ended up sounding just like every other daytime talk-show host. And the world looked at what the church was offering and thought, This is just more of the same. What’s interesting about it?

Thomas: The world can do a better TED Talk than the church. MTV can do a better concert than the church. So if your church is just a TED Talk and a concert, you’re never going to out-TED Talk or out-concert the world.

Chase: There’s a trap here for writers too. If I’m just trying to write another self-help book that applies some Christian scriptures, that book has probably already been written, and probably written better by someone else. It’s likely not offering a unique enough perspective on the world to capture people’s interest.

More and more, if you look at the voices who are really growing, such as Jordan Peterson and Joe Rogan, they’re not what you’d traditionally call “relevant.” If anything, they’re often provocative. But what they have is a cohesive worldview that stands out from everything else being said.

Jordan Peterson has a coherent worldview. Rogan may not have a cohesive worldview, but he does have an approach to developing a worldview. He has a unique system by which he tries to ascertain the truth. Their audiences are drawn to them because they’re not going to hear those perspectives anywhere else. Whether you agree or disagree, you’re getting something different; and that uniqueness is becoming increasingly important.

Many traditional media institutions are collapsing because when people tune in, they already know exactly what they’re going to hear. That predictability isn’t compelling anymore. People are looking for someone who will say something unique.

Now, this trend has both positives and negatives. On the positive side, it opens the door to hearing truths we might not otherwise consider. On the negative side, it can lead people down dark paths, always chasing the next novel idea. Scripture warns us about this too. In 2 Timothy 3:4, we read that in the end times, people will gather teachers to say what their itching ears want to hear. The pursuit of novelty can pull us away from the truth.

Still, as Christians, we must learn to articulate what we believe in a way that sounds unique. We don’t want to be “relevant” in that we sound like everyone else, but “irrelevant” in the sense that we sound different from everyone else. Our message shouldn’t simply fit into the existing conversation. It should stand apart. In doing so, it becomes truly relevant for the world today.

Thomas: The Catholic church with the Latin masses had nothing “relevant” about it. The building, forms, and liturgy were ancient. The acoustics weren’t designed for modern speakers, and they hadn’t made any accommodations for a sound system. Yet, it was packed with young people. College-age kids were filling that service.

Chasing relevance and assuming it’s the answer is a mistake. Relevance isn’t the answer. That doesn’t mean we can speak German to an English-speaking audience; we still have to be present in the culture. But a big part of that presence is listening and understanding what’s actually holding people back.

If you talk to non-Christians, their objections aren’t usually to Christianity’s truth claims. It’s the moral claims they push back against. Christians have become so afraid of our own morality that we’ve failed to recognize its strength. The Christian moral system is actually superior to the one the world is offering.

Take the idea that people can do anything they want as long as it’s consensual. That sounds permissive and freeing, but it’s disordered and unhealthy. We’re seeing the consequences of that in the Diddy trial. Horrible things are being revealed, and the defense is essentially arguing, “This awful act was consensual, so it was fine.” But we’re starting to see that consent as the highest moral value is a bad foundation for a moral system.

Chase: We’re also seeing a trend where some of the more radical ideas of postmodernism are starting to burn themselves out. They’re reaching a point of absurdity, and people are beginning to recognize exactly what you’re describing.

At first, it sounds appealing to say that each person should be free to choose the truth that works for them, and that no one has the right to judge someone else’s truth. Philosophically, there may be an entry point into that idea that feels compelling. But as it plays out, and as people begin to explore the limits of that worldview, it leads to places most people recognize as unhealthy for individuals, relationships, cultures, or societies.

One of the big, disorienting moments over the past year has been how quickly some of these conversations have shifted. Even in the aftermath of the presidential election, it feels like we’re pivoting back toward a modernist worldview. I’m hearing more nonscientific people talk about scientific studies. They’re trying to dig in and research for themselves. There’s a growing interest in how truth is discovered, more than I’ve ever seen before.

The world is shifting around us. It’s partly because we’re beginning to see where the postmodern paradigm ultimately leads, and it ends up being a fairly meaningless worldview.

Finding the Current Zeitgeist in the Old Testament

Thomas: One of the wonderful things about the Old Testament is that it spans such a long period of time. You can usually find your current cultural moment reflected somewhere within it.

If you follow the story of the Jews (from a single family to slaves in Egypt to tribes to a unified nation to a divided kingdom, then conquered and returned), you’ll find a postmodern era in there too. In fact, there’s an entire book of the Bible where “everyone did what was right in their own eyes.”

What’s striking is that it starts off fairly well. The book of Judges opens with a righteous people who fall away but then return. But each time they return, they don’t come back quite as strong.

What really stands out to me is that refrain, “They did what was right in their own eyes.” The next part of that sentence is political: “because there was no king in Israel.” It shows that religion and politics aren’t separate; they’re deeply intertwined, in ways we often overlook.

Right now, we’re living in a time where people are doing what’s right in their own eyes. Just as in Judges, that path eventually leads to moral decay so horrific that it can’t be ignored. That’s when the consequences become extreme. The book of Judges ends with the near-total destruction of the tribe of Benjamin. Only about 150 men are left because the rest were wiped out in response to a terrible act of collective wickedness.

The book of Judges shows us that moral decay can end in genocide.

It’s a disturbing cycle; and when you look at it, you’re left wondering who was in the right. The whole situation is tragic. It’s a warning. If we don’t repent, we may find ourselves in the same place. And that’s not where we want to go.

Chase: I always think of the book of Judges as a spiral of stories. Each judge is based on the same narrative structure; but as they progress, that spiral begins to destabilize and swing wider and wider. By the end of the book, it unravels and flies apart into chaos. It’s what you’re describing.

Thomas: And the restoration all started with the prayers of one righteous woman (1 Samuel 1:10). She was praying so fervently she wept while she prayed, but the religious institution was so corrupt, the high priest saw this righteous woman praying fervently and didn’t even recognize it. He thought she was drunk (1 Samuel 1:13). That’s how corrupt the culture was.

But God heard the prayers of that one righteous woman, and it changed the course of everything. She had a baby named Samuel. The revival that followed was so intense that even Saul was among the prophets (1 Samuel 10:11; 19:24).

So don’t despair. Pray fervently and be aware of the time so that we’re ready to give an answer for the hope that lies within us.

Can apolitical Christianity exist?

Chase: The political question is really at the heart of this, and probably the one I’m still working out and still have questions about myself.

I have been a pastor in the era where the pastor’s job is, as much as possible, to be apolitical.

I have not talked from the pulpit about who I’m voting for. I’ve talked at various times about particular issues. I have people in my congregation who are of different political persuasions, although they would agree on many of the core issues. It’s getting harder for that to be true as the political parties become more radically different.

I want to pastor the people in front of me, and I don’t want to allow what I’m preaching or doing to slip into the political categories. Now, the hard part of that is that everything has become political, and this is what has changed.

Thomas: Physical fitness is now apparently a political statement. Going to the gym is considered a right-coded activity. I had no idea.

Chase: I’ve read those articles too. What’s becoming increasingly difficult is that it’s not just speaking that’s political now; silence is political too. That’s been one of the hardest things to navigate: choosing not to take a public stand on certain issues is often interpreted as making a political statement in itself. So even this conversation we’re having, to some degree, is part of the political discourse, whether we intend it to be or not.

We must be careful that our message is not political in nature, but that it does engage with the political. The reason I put it that way is because I have very little confidence in the government’s ability to bring about the kind of moral change our country truly needs. That said, I do hope we elect a kind of government that allows moral change to flourish in the lives of individuals.

But if we reduce political engagement to simply supporting a particular politician or party, we’re missing the deeper responsibility we have as Christians. We’re called to lead the conversations that are political, but to lead them from a place of moral and biblical conviction. We should be articulating what Scripture says about these issues, which will likely be interpreted as political speech. But that’s very different from tying ourselves to a politician or placing our hope in a political party.

Honestly, I’m skeptical even when politicians court Christians. I wonder how much they truly believe what they claim versus how much they just see us as a voting bloc. But that’s the nature of our political system.

So yes, I believe we must be willing to engage political questions. Writers, even more than pastors, are uniquely positioned to do that in a powerful and effective way.

But as a Christian, do I really need to be worried about politics?

Thomas: As a writer, you’re not in the best position to back a person because people change.

I was recently watching a debate in the Texas legislature, where I used to work as a staffer twenty years ago. As I watched, I didn’t recognize a single face. They were all new to me. But the ideas being debated were familiar. The faces were different, but the ideas remained the same.

That’s the danger in attaching yourself too closely to a person. People are flawed. Even the most principled, righteous statesman will eventually die, retire, or get sick. But ideas persist.

Marx’s ideas have led to more deaths than all the religious wars in history combined. He’s been dead a long time, but his ideas still wreak havoc. Around the world, people are still being imprisoned and killed in the name of trying to fulfill one dead man’s utopian vision.

This is why the arena of ideas is where writers have real influence. A book can outlive its author. The Communist Manifesto isn’t going away. Marx is gone. Lenin is gone. Mao is gone, but Mao’s Little Red Book is still around. That’s why we must contend with ideas.

I’m still torn on the question of leaders, because winning elections does matter. Governments matter. When a government turns against Christianity, the Christian faith often fades in that region. There was a myth passed around in the 20th century that persecution is good for the church, and that communism in Eastern Europe was somehow strengthening Christianity. But history doesn’t support that.

When the Turks took over Constantinople, the church didn’t thrive there. Today, Istanbul has virtually no Christians. The same is true in places like Libya and Syria. But Spain is a different story. After a long war, the Christians won, changed the government, and Spain remained a Christian country for centuries.

I don’t claim to have all the answers, but I do believe it’s naïve to say, “I don’t need to worry about politics.”

Chase: As an author, I’m aware that if I write a book tied to a specific election, it will have a very short shelf life. I’ve tried hard to write about the issues in front of me today, but I also believe that authors can dig down to the foundational ideas beneath those issues. The ideas themselves are often more enduring than the political party or individual.

If I only write about what’s happening on the surface, then I end up adopting the same political rhetoric everyone else is using. And honestly, that’s a great way to sell books right now. I’ve noticed that the books selling well are the ones that basically affirm what people already believe and give them the language to express it.

Thomas: They’re books that say, “You are a good and just person, and everyone who disagrees with you is evil.”

Chase: Exactly. So you can hand it to your friend and say, “See? This is right,” because the author has articulated what you already think. To be fair, there’s a place for those books. But I’m trying to do something different. I want to challenge people to think differently. I want to engage people in a way that moves them toward change and ultimately toward faith in Christ.

To do that, you have to push the conversation deeper. You have to recognize the issues beneath the surface that are driving the political language and cultural clichés.

You modeled that in your opening. It wasn’t about why someone should vote Republican or support a certain party. It was about recognizing how the world is changing, how that’s shaping our perception of faith, and how we can talk about those changes in ways that deepen our understanding of who we are, what our faith is, and what it means to live faithfully right now.

That’s the hard work. If we’re not working hard at it, we’ll naturally slip into the shallow political language and cultural clichés that are so easy to borrow.

How the Left Is Offering “Another Gospel”

Thomas: This matters because the left is presenting a false gospel. They have a false definition of sin with no hope of redemption. According to this view, if you’re an oppressor, especially a white oppressor, there’s nothing you can do to stop being one. You’re simply damned in a literal sense. You are damned in your sins, with no one to save you. You can’t fix your whiteness.

At the same time, people feel guilty, often because of the sexual things they’re doing, because deep down, they have a conscience. They know right from wrong. Scripture says the law is written on their hearts, and their consciences bear witness to it (Romans 2:15). So people are experiencing guilt from their sexual sin, and they’re being handed a false gospel that says, “You feel guilty because you’re an oppressor, a colonizer, and there’s no hope for you.”

That’s incredibly destructive. It leads to despair, to unhealthy behaviors, even to suicide.

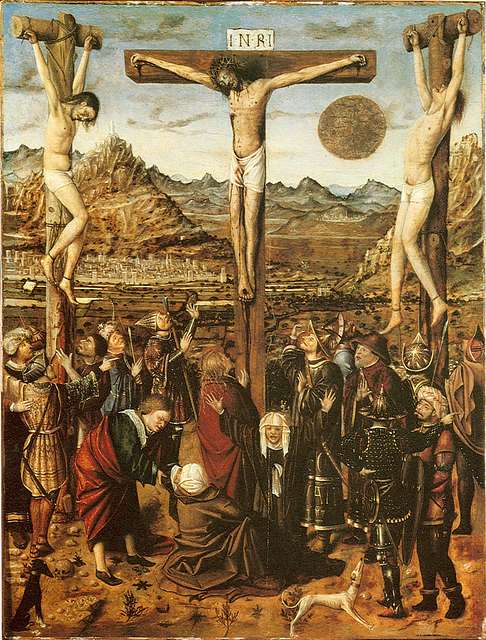

But as Christians, we have the real answer. The gospel is a beautiful thing. Following Christ is a beautiful thing. Christ came into a world where Romans and Jews hated each other, where there was a long history of violence between them, and he died for all of them.

Who killed Christ? The Romans and the Jews.

Original public domain image from Statens Museum for Kunst

Who did he die for? Both of them. Who does he save? All of them. The master and the slave. The man and the woman. That’s the good news of the gospel.

So, if you’re feeling the weight of your sin, if you’re honest with yourself in your quiet moments and feel that burden, there is hope! Not the false hope of acknowledging your whiteness and staying condemned, but real salvation. That salvation is only found through the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ.

Chase: Christian authors can offer something uniquely Christian. Christianity has something distinct to say among all the worldviews. But if your writing is just applying Christian scriptures to an already existing belief system, which happens more and more in Christian publishing, then you’re not saying anything new. You’re not offering anything truly meaningful or transformative.

We need writers who can see how the Christian faith speaks into today’s conversations in a distinct and compelling way. That’s what makes writing powerful and worth reading.

How do authors protect themselves from shaping Scripture, rather than being shaped by it?

Thomas: Today I can go to AI and say, “I have this position. Give me Bible verses that support it,” and it will instantly produce a list of verses that appear to support that position. Whether they truly do or not is beside the point. AI doesn’t care. And that makes it dangerously easy to shape Scripture to fit our views instead of allowing Scripture to shape us.

Look for the Root

Chase: You have to look for the issues beneath the clichés. The worst form of writing is cliché. That includes overused phrases, as well as clichéd ideas that have been repeated so often they’ve lost clarity or meaning. If you’re leaning on clichés, you’re not really saying anything new or thoughtful. That’s the death of good writing and of clear thinking.

First, we can’t afford to rely on mental shortcuts or prepackaged language. We have to genuinely wrestle with what we believe and try to understand what’s happening in the conversations we’re having.

Apply Truth in Real Life

Second, we have to live this stuff. It’s easy for us as writers to consume news and debates online, then retreat to our laptops and write books, never having implemented these ideas in our own lives, in the lives of a congregation, or in the lives of nonbelievers.

What we’re doing in this conversation is really interesting. We’re actually talking about these ideas and refining them. In my own writing, I try to do the same by discussing the ideas with others. Some writers love to go off into the woods and write undistracted from everything and not tell anyone about it until it’s a completed work. That’s fine if you’ve spent years living and working through the material already. But most of us need to be talking about these things.

We need to test them through a YouTube channel, a podcast, social media, or one-on-one conversations. If we don’t, we risk recycling the same clichés and failing to contribute anything meaningful to the conversation.

Read Old Writings

Thomas: It’s absolutely what will happen if you’re not careful, because we all live in the same culture. We’re all breathing the same air, watching the same movies, and experiencing the same historical events that shape our views.

One way to prevent that is to read really old books.

I grew up in a very low church, the lowest-of-low church. At one point, my parents left the low nondenominational church we were at, and we joined a home church. There was no floor beneath us in terms of the high to low church continuum, and there was not a high view of church fathers.

I did not grow up reading any of the church fathers. I only grew up reading the Bible, which is far superior. But just because the Bible is better, I have come to learn that the church fathers are helpful too. When it comes to understanding the culture and the challenges that other Christians throughout the ages have faced, reading the church fathers is surprisingly helpful.

For instance, the Jehovah’s Witnesses are a cult, and they have some views of Christ that are not orthodox. If you’re not familiar with church history, you may think these are new heresies. But they’re not new; they’re ancient. We’ve had councils on these heresies, and there are well-established defenses that have been proven through trial and intellectual combat over centuries. We could reinvent those arguments with lots of effort, or we could read the church fathers and stand on the shoulders of giants.

A man in my church, whom I really respect, started listening to translations of sermons that were 1,000 years old or older. I remember him talking about a sermon from John Chrysostom in 400 AD, and he said it sounded like a sermon from today.

They were dealing with the same kinds of questions we are. The objections the preacher was responding to were the same kinds of objections people have today. It’s easy to think we are special, that we have special technology, that humans have never faced these problems before, and that our ancestors have nothing to help us. But Solomon said there’s nothing new under the sun (Ecclesiastes 1:9), and he was right.

We read old books, study history, and read old writers because our questions have been answered multiple times throughout history. We don’t need to exclude modern works because we need to understand the questions that are being asked, but we can also learn from historical answers.

Nobody is accusing Christianity of being an atheistic religion anymore. We answered that question. Nobody’s accusing Christianity of being polytheistic, at least not in good faith. We’ve answered that question, but there are other questions that keep coming around. For example, Gnosticism won’t go away.

Research the History of the Conversation

Chase: I often spend a year on a book; and, usually, there are threads of ideas that go further back from what I’ve read and thought. I’m trying to find the thread of the conversation through history.

It’s exactly what you’re talking about. I want to understand where the conversation is happening today, but I want to figure out who has been thinking about this longer than I have. From the Scripture through the various parts of church history, where has this conversation gone? Once I get ahold of that and read through it, it’s amazing how much it clarifies our moment and helps us understand where we are, based on those historical conversations.

That’s an important part of my writing.

Search Your Heart

The other thing I would say is that I feel pretty strongly about controversial topics. The way I say it to myself is, “If somebody has to pay for the point, it has to be me.” What I mean by that is the points are made best when the villain or the negative examples come from my own life.

That doesn’t mean you can’t reference thinkers where these wrong ideas have come from or where I see them showing up in culture. But I’m really aware that whatever is broken and wrong in the world is also broken and wrong in my own heart. Though my sins may not have played themselves out to the same places, whatever has led to that point in culture, the seeds of that are in my own idolatry, my own sin.

When you can track the cultural issues back to the core ideas and then track those core ideas back into your own heart and the temptations you’ve experienced, you posture yourself to write about these things on a much deeper level.

If you’re just wanting to convince people who are already convinced and sell books, go ahead. But if you’re writing to genuinely try to change somebody’s mind on something, you have to pay the price for the point. It’s got to be at my expense, which means I have to work these ideas out in my own heart. You have to recognize how you could go down the same road.

That’s something Jordan Peterson does a lot. One of the big things he spent time thinking about was how it was possible to have been a worker in a concentration camp. One of his final conclusions is that any of us could have done it. It wasn’t an extreme person; the seeds of that are in every single person’s heart. His realization that it could have been him is what set him on the path to try to build a morality that would protect him from those kinds of temptations. That’s the same idea. Anything you’re writing about, you’ve got to track it back into your own heart.

Thomas: There’s an old saying, “There but by the grace of God, go I.”

It’s an old saying, but my dad once translated it as, “Except for God’s grace, I’d do it too.” It’s the same concept that Jordan Peterson is talking about.

Suddenly, you realized, “That could be me.” It gives you that gentleness. Going back to that passage from Peter at the very beginning, it’s not just giving an answer. It’s answering with gentleness.

How you say it is as important as what you say, particularly in this era of pathos, where it’s not about the truth. That’s not really what people are hung up about. It’s about the feelings, and how you say what you say is really important.

My pastor, just this last Sunday, was responding to some bad theology from other Christians. He read a couple of quotes from other Christian leaders that he was rebutting in his sermon. I don’t know if he had planned to do this from the beginning or at the last minute, but he didn’t read the names of the people who said those things. It made the arguments so much stronger because if he had read the name of the person, suddenly my view of that person would have colored his commentary.

But since it was just the statement separated from the person, I could objectively ask myself, “Is that something I believe? What does the Bible say about that?” It made it a much more powerful point.

You don’t have to have struggled with a sin to confront the sin. Elijah didn’t say, “I was once a Baal worshiper like you, and then I saw the light, and now I’m not a Baal worshiper.” He never worshiped Baal. And, it was okay for him to criticize the Baal worshipers.

But there is a way to do it with gentleness. If you don’t make a punching bag of a person and instead make a punching bag of the idea, it makes it easier for that person to repent of the idea because they’re a little more separated from that bad idea.

Speak Directly

Chase: There may be times when we are called to say things extremely directly, so it doesn’t mean I’m unwilling to do it. I just refuse to let that be my knee-jerk reaction. I’m often trying to discern by prayer in the Spirit, “Is this my thing to say?”

Because the truth is, I have strong opinions about every political topic. I follow politics closely, and I’m interested. That doesn’t mean I’m always right. Just because I have an idea doesn’t mean I’m right. But if I think my idea is Christianity’s idea, everyone should believe it, and I should write a book on it, that’s probably not right. At some point, I’ve probably missed something.

So, I’m really trying to discern what is something I’m just passionate about, what is something meant for me and my family and friends, what is something that’s an article, and what is something worth the investment of writing a book.

Think about the authors who have impacted you the most. Most of them have an impact in particular areas or have written particular points that have defined their work.

I write pretty broadly, but I’m still always trying to discern what the Lord really wants me to speak about. It doesn’t mean I’m unwilling to give an answer on other topics, but I try to discern where he is asking me to lead or to speak out.

That’s a harder conversation than it’s ever been because you can blast off a tweet or a Facebook post so fast on just about anything. Again, it doesn’t mean you shouldn’t, but I want to have enough pause and discernment to ensure that this is the time, place, and topic I, in particular, am supposed to be speaking on.

Take Courage

Thomas: It takes courage to write a good book. It takes courage to speak the truth, especially if it’s an uncomfortable truth. It also takes courage to be understood.

Sometimes we hide behind too many qualifications and don’t just say the truth plainly because we’re afraid of criticism. For example, we might present an absolute truth, as true in most cases. We hedge so we can’t be criticized.

It also takes courage to publish the book. It’s easy to write a book or blog and not publish. On the other hand, it’s easy to blast something out there when we’re angry and dunk on our enemies, and say, “I’ll tell you on Twitter what I really think!”

We’re called to have courage and wisdom, but we’re also called to be prudent. This is a dance. There are no easy answers here. The call of apologetics is not an easy call. Apologists get fed to the lions; they get their heads cut off by Muslim conquerors.

This is not an easy job, but Jesus is with us; and if we endure to the end, we’ll be saved (see Matthew 24:13).

Evaluate Your Motive

Chase: If you find that you never take the risk, it’s often a sign of cowardice. I wrestle with the same questions. Am I holding back because I’m not the right person to speak? Am I holding back because it’s not the right time? Or am I simply afraid to speak up?

If you find yourself constantly feeling compelled to write on something and then pulling back from it, pay attention to that. That’s probably evidence that you need to take courage and risk something for your writing. Follow where that prompt is leading you.

Fear Not

Thomas: That thing you’re most afraid to say, everybody else is probably afraid to say as well.

From a marketing perspective, if you’re the first one to have the courage to say it, your sales will be easier. If you’re the tenth person to write the book on the topic, nobody wants to buy it. But if you’re the first one to take that bold stand, everyone will be talking about your book because you took a courageous stand on the issue.

There are lots of issues. Christian morality is complex. It speaks to every aspect of our lives. In some areas, such as dating and relationships, it’s frustratingly vague. That’s the one topic where Paul says, “This is just me, not God. I’m not entirely sure.” But in other areas, Christian morality is very clear.

One aspect of this current age is the concept of buffet religion. People want to be “spiritual but not religious,” so they can choose their religion and beliefs, rather than religion choosing them.

We don’t get to pick what Christianity teaches. We only get to choose whether to surrender to Christ or live in rebellion against Christ.

That moral clarity is difficult, especially in a time when people want to take the parts they like and leave the parts they don’t like. People are also prone to throw around the word “context” as a way of saying the passage doesn’t mean what it says.

Context isn’t a magical word for not having to surrender to Scripture. There’s a time for understanding the context, but there’s also a time for saying, “I don’t like that the Bible says this, but I will acknowledge that God is God, and I’m not.”

Cherish Community

Chase: You and I had a conversation once about the value of writers going to church. We have both observed a tendency for writers to become frustrated with the church and want to distance themselves from its complexities.

But that’s part of the answer here too. Where does that courage come from? It comes from our relationship with Christ, but it also comes from the witness of one another, spurring one another on to greater faith.

At the end of the day, if I spoke out and lost everything, if I got canceled and my whole writing career dried up, if I packed it up and got a job at the grocery store, I would still have my church. We believe the same things. Since I’m accountable to them, those are some of the most important relationships in my life. Having those relationships, where we agree together on these core issues, becomes a massive stabilizing force and builds courage.

Writing is even harder if you don’t have a church community around you.

Thomas: Having a church community around you protects you but also gives you courage.

When I wrote my book, one of my beta readers was my pastor. I specifically sought him out and wanted him to look it over. I said, “I want you to make sure that I’m on the orthodox page here, that I’m not accidentally promoting bad doctrine or making some mistake.”

Then, I accepted every single one of his changes. Some of them were things that readers could have misunderstood. He didn’t have a lot of changes; but knowing that my pastor had read my book, that I had tweaked it, and that he was behind me was really encouraging because my book was very controversial.

Thousands of people were angry at me over the blog posts that led to the book. But we were able to have the launch party at our church fellowship hall. When people were attacking me and disparaging my character on the internet, people from my church were defending me, saying, “I know him. You don’t. What you’re saying is not true.”

That was so encouraging, and it helped me take a courageous stance.

Christ is with you, but it’s not just you and Jesus against the forces of darkness. You have his church with you as well. You have brothers and sisters in Christ who will, like that Roman hoplite, link their shields together. Your shield covers you and the person standing beside you. Defending the faith is not something you do alone. It’s something the body of Christ does together.

Chase: You see that so faithfully through the Scriptures. When the disciples are in jail, the church is praying for them behind closed doors. They suffer and face the consequences together too.

I’ve experienced the support of my church too. Just like you, I’ve written on the controversial topic of masculinity. I wrote a book on offense, and I’m working on a book about the physical body. Talk about dangerous, controversial topics!

Having people who will read those with me, make sure I’m saying what I want to say, and not accidentally saying something I don’t intend, is so valuable. Having people supporting me is a totally different experience from flinging books from my desk by myself.

Defending the Faith in Many American Cultures

Thomas: What final encouragement do you have for people who want to give a defense for the hope that lies within them and are wondering how to do that in this new zeitgeist?

Chase: I’m less convinced there is a single “American culture,” and I’m more convinced that there are thousands of American cultures. If you need any proof, check out the Instagram Reels or TikTok videos of your kids, teenagers, or friends of different ages and compare them to yours.

They are living in an entirely different world than you are, with different voices and messages. We no longer have five media companies controlling the narrative. Any person with a microphone and a camera, at any age and in any place, is controlling the culture. The days in which we’re going to have single messengers like a Billy Graham or single messages like “Your Best Life Now” or “Purpose-Driven Life” are behind us.

What we need at this moment is not one person who can stand up and address all of culture, but we need a lot of Christians in many different cultures bringing their faith into those particular conversations.

So, be careful with the idea “I will stand for faith, and I will sort out our culture.” I’m not even sure that exists, let alone if any of us is capable of it.

Look very carefully at where God has placed you. What conversations are you already in? Who are you already dialoging with? Ask yourself, “How can I serve as a faithful witness to this group of people, with these particular questions?” Those will become the most relevant questions and the most helpful for effectively spreading the gospel and giving a defense in culture today.

Thomas: That’s well said and very important. It actually goes back to the Roman and Muslim critiques of Christianity being very different. Modern thinkers still exist even though society as a whole has shifted into a postmodern way of thinking.

Modern people are still raising modern objections. In fact, I was talking with the woman who cuts my hair. She’s a believer, and she often talks about the Bible with her clients. She mentioned a conversation she had with a man who was bringing up scientific objections to Christianity.

I asked, “How old is he?” She said, “Oh, probably in his fifties or sixties.” And I thought, That makes sense. He grew up in the 20th century. He’s very much a product of his time. His children or grandchildren likely don’t have those same kinds of questions, but his questions are still holding him back.

He’s still wrestling with modern-era questions about miracles and the inerrancy of Scripture. And those questions still need thoughtful, honest answers.

As you focus your message, you can tailor it in a way that they are able to hear it.

Paul never quoted the Bible when preaching to a Greek audience. He would instead speak from his own personal experiences because Greeks didn’t care what the Hebrews wrote in their Scriptures ages ago. But when he spoke to a Jewish audience, he quoted the Old Testament all the time because his Jewish audience did care.

Knowing what somebody finds authoritative and tailoring your message to the questions they’re asking can make your apologetics much more effective.

Chase: Each of us discovers that as a writer. I’ve discovered more and more that I’m writing to men. When I set out, I did not imagine myself to be a men’s writer. I never set out to build a men’s ministry; but my audience, conversations, and the Lord’s leading have brought me here.

You can bristle at that and refuse, or you can say, “I will steward well the opportunities the Lord has put in front of me.” Part of being a writer is learning to recognize those and write into those.

Thomas: Pro tip: If God calls you to go to Nineveh, just go to Nineveh.

Chase: Good advice.

“Your truth, boomer, is not mine,

and I think you will find that

it will blow your Nineties mind

that I identify as Cat.”

“Well, that is really cool,” I say,

“so bless your cotton socks,

but I must ask you, if I may,

do you need a litter box?”

“Oh, you vile and hateful man,

my feelings are SO HURT!

I can see your wicked plan

to say I do it in the dirt!”

And that’s sum of postmodernity,

a prideful inconsistency.

OMG Andrew, I thought I had seen one of your home runs, but this is out of the park! Thank you.

George, thank YOU! You made my day!

George, that’s an Amen from me!

Staggering insight. I’ll chew on this a long time.

“The gingham dog and the calico cat”–ate each other up.

Listen to the music today. Study the lyrics. Pure inconsistency.

Gentlemen, you’ve given me a lot to think about, especially with my outreach to young people. Thank you.

This one is worth a second and third read. Deep but very important and timely.

Thank you for the courage to speak to this with clarity and honesty and truth.

Karen, I completely agree with you.

While I agree with many of your premises I am horrified by your deification of Trump. If he is your example of a someone with a moral compass I can’t imagine what kind of Christian moral ethics you follow. You mentioned conservative Catholics as having the right ideas that attract many young people. As one of those conservative Catholics I whole heartedly agree, but I feel like BOTH parties have lost any kind of real moral compass. If you truly think Trump is the answer, maybe you should read what the pope and the council of Catholic bishops have to say about the current administrations policies.

Mary, I, too, am a conservative Catholic, and certainly not a deifier of Donald Trump (I don’t think Thomas and Chase are, either) but I have found recent statements from the Vatican seriously flawed.

This, Pope Leo’s statement on the bombing of Iranian nuclear sites from EWTN Vatican:

“There are no distant conflicts when human dignity is at stake,” he said. “War does not solve problems — on the contrary, it amplifies them and inflicts deep wounds on the history of nations that take generations to heal.”

The pope also evoked the most heartbreaking human toll of violence. “No armed victory can make up for a mother’s grief, a child’s fear, or a stolen future.”

Finally, he renewed his call for diplomacy and commitment to peace: “Let diplomacy silence the weapons; let nations shape their future through works of peace, not through violence and bloody conflict.”

I see three errors, one per paragraph.

First, war can certainly solve problems. We might look to Samuel’s advising Saul on how to deal with the Amalekytes, or to the more recent example of the need for destroying Hitler’s regime. The wound of Nazism on the German national psyche was certainly deeper and more severe than the Allies’ rough surgery.

Second, appealing to the emotional images of a mother’s grief, a child’s fear, and a stolen future are meaningless without context. Their universality has to be viewed through that lens, otherwise a deconstructive equity is introduced in which righteous wrath and warmaking is stayed by sentimentality for, say, the future of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere and its brutality towards China.

Third, Christ Himself used the metaphor of bringing not peace, but a sword, and did He not chase the Temple moneychangers with a whip? Diplomacy has an end, and beyond that the starkness of division must be addressed with sure firmness. There was no negotiating with Usama bin Ladin, nor with ISIS, save allowing more grainy videos of innocents in orange boiler-suits being slowly beheaded.

I have trenendous respect for the Church, and for the institutions of the papacy and the bishopric, but these are human constructs… divinely inspired, of course, but composed of fallible, sinning men.

We follow Christ, and are guided, yes, by Apostolic wisdom, but we can never let that guidance turn faith into a spiritual game of crack-the-whip, in which we, as the last man, are flung off.

Thank you, Thomas, for a comprehensive and thought-provoking blog. As many others have, I, too, have steered away from politics. You make a good point.

A lot of our perception is guided/misguided by what we allow ourselves to listen to and absorb. So many of the commentators are all about making statements condemning others but offer no alternative solutions that make sense. I think they are losing sight of the big picture. No one is perfect, except Jesus Christ. No political party is perfect. But what do they stand for, not against? How can anyone face God when they vote for someone who advocates killing babies? A life, a person made in the image of God? Well, this could go on forever, but I appreciate the fact that you have addressed the subject.

Thank you, this is so helpful! We must answer the questions readers ask, not the old ones we’re used to (if we’re old, haha!).

The absence of Christian voices in the public square allows the enemy to steal, kill, and destroy, unopposed. Living in a deep-blue county, I see this every day. It’s heartbreaking. And yes, it takes courage to speak up on the most controversial points. But as Christian writers, we must speak the truth, even on the points that will cost us. If we don’t, innocent people suffer. And God will hold us accountable.

I’m reading When Culture Hates You by Natasha Crain. It’s a deep dive into this issue. It’s helping me understand the thinking/ideas behind the issues, and how to challenge them as I complete my work-in-progress.

Columba, I completely agree with you.

Didn’t think I would make it through in one day, but I’m so glad I did. This article was inspiring and informative from start to finish, true food for thought.

I especially appreciated the mention of traditional Catholic churches. A young priest came to the church we currently attend around the same time as we moved to the area. A few years later, the church is thriving more than ever after he incorporated some more traditional practices. Even the small changes made a huge difference.

I completely agree with you,

Such great content! After going to university and doing campus evangelism for several years, I’ve been disturbed to find many pastors still seeking to make their church “relevant,” the exact opposite of what young people trying to escape the repercussions of postmodern thinking are looking for. Our culture is desperate for an antidote to the “freedom” that they’ve been sold. This was a refreshing read! Thanks for addressing this issue with such clarity and thoughtfulness.

I completely agree with you.

I have been researching our Holy Scriptures and the Quran for 30 years. I’m a scientist, who seeks consistent truth and I’m a devout Christian. I have found the consistent truth in the Epistle of James, which applies to Jews, Catholics, Protestants, and Muslims. The cover for the book I’m now writing says:

Book Title: Hey! Rabbis, Priests, Pastors, and Imams Stop Teaching Conflicting-Religious Concepts

Subtitle: Our Lord’s Consistent Truths Can Unite Us All!

Promise: Evidence for our unity is given in this book.

Quote: “We teachers are judged more severely.” James 3:1

Thank you and may the Lord bless you and yours, John.

John P. Hageman, MS, CHP

Author of: The Bible’s Hidden Treasure – James the Precious Pearl

Wow, what profound thoughts, and well worth the time to read through to the end. In fact, would you consider offering this in printed booklet form? Thanks!

Well said. Thank you. Those who are looking for moral leaders in politics are missing the point. We’re all flawed, some more than others. Politicians have evolved into greedy, selfish, liars. It’s often a choice between evil and bad. We need to reject the evil ones and discern which policies reflect our morals. We mustn’t wait for perfect politicians, Modern saints seldom choose politics as a career.

Thomas, this post is embarrassingly bad. Deconstruction is not about “attacking Christianity”. It’s about intellectual integrity, which is thoroughly biblical. It’s about putting away childish things, which is thoroughly biblical. When Abraham left the polytheism he was raised in to follow the One God, that was deconstruction. When the apostle Paul left the religious nationalism he was raised in to follow the Prince of Peace, that was deconstruction. When Martin Luther nailed his 95 theses on the door, that was deconstruction. When Lee Strobel wrote THE CASE FOR THE CREATOR, in which he argued that the evidence for the Big Bang is evidence for a creator, that was deconstruction from the bad-science young-earth creationism that many of us grew up on. Millions of devout Christians have deconstructed from the pernicious theology they were raised on. You owe them all an apology.

Randy, I respectfully disagree.

Neither Abraham’s, nor Paul’s turn to God was deconstruction; both were Divine calls, in which each man was the recipient of Truth, and not its agent.

Martin Luther and Lee Strobel… I don’t know. But I do suspect that theological deconstruction is a dangerous practice, to be approached with trepidation.. Good things may arise when a temporal point of view (even that of an established church) is challenged, but so also may divergence from Scripture be introduced.

You can claim that Abraham and Paul didn’t deconstruct, but of course they did. They made a paradigm shift. God called them, but they made the decision to follow and leave the life they had been living. God is calling conservative Christians now to deconstruct–to put away the childish things that they accepted because somebody in authority told them to. Millions have accepted the call and have grown in their faith as a result. Just as one example, it’s now pretty common among evangelicals to accept the Big Bang. See Lee Strobel’s book, or read the Christian philosopher, William Lane Craig, who has made the Kalam argument a cornerstone of his philosophy, in which the Big Bang plays a central role in his argument for the existence of God. Or read just about any book by Pete Enns. I would recommend his book THE SIN OF CERTAINTY if you’re just starting out on your deconstruction journey.

Hi, Randy! I know you are a highly educated, successful individual, but based on this comment, I can only conclude you have not studied the origin and history of deconstruction as a philosophy nor followed the recent trends in younger generations of Christians. I recommend you do so. Deconstruction is the critical philosophy of atheist Jacques Derrida. It is not a word than can be applied retroactively to historical conversions nor to modern religious people who modify some of their doctrine within their faith after research and/or soul-searching. Therefore, the examples you gave are not deconstruction.

Coming from the millennial generation, I have seen friends and peers deconstruct their faith. Without exception, this means rejecting Christianity and becoming atheist or agnostic (see YouTubers Rhett and Link for celebrity examples). At best, deconstructionists may claim to still be Christians but preach an unbiblical gospel of tolerance for continuing in a life of sin.

In practice, then, converting from one religion to Christianity is not “deconstruction.” Moving from one Christian school of thought to another is not “deconstruction.” Rejecting true Christian faith for something else (from redefinition of sin to outright Godlessness) is. Everything Thomas said in his intro is 100% accurate, and I don’t think it would take you much research to verify it.

No, “deconstruction,” as commonly used to refer to the paradigm shifts that millions of Christians have made, has little to do with Derrida’s work on deconstruction. I define deconstruction in this context as “putting away childish things.” It is simply false to say that everybody who deconstructs becomes an atheist or an agnostic. I have been deconstructing for about 60 years, and I’m still a Christian. Millions of current Christians have deconstructed their faith and are better Christians for it. Thomas made numerous blunders in his post. The whole thing is just embarrassing. I say this as a longtime friend of Thomas. Just as one example, his attempt to connect porn to deconstruction (or to becoming a Democrat) is just weird. His comments about climate change being a lie is weird. And as I noted, Lee Strobel, in his book THE CASE FOR THE CREATOR, embraces the Big Bang–something that would have got him vilified as a heretic in the church I grew up in. Thomas appears to think Lee is a terrific apologist. And yet Lee has clearly deconstructed from the young-earth creationism that most conservative Christians grew up with. And Thomas seems to be OK with that. So is a little deconstruction OK, as long as it’s the right kind?

Randy, I appreciate the reply. However, I stand by my previous comment and maintain that what you are describing as deconstruction is not what the term means in practice. Also, the word as it applies to faith is 100% derived from Derrida’s term and, like Derrida’s deconstruction, seeks to “tear apart” the subject at hand.

I would be curious to know if you have been calling your own faith journey “deconstruction” for the past 60 years or if you dubbed it “deconstruction” after you heard the term sometime thereafter and thought the word described your experience. You are welcome to assign your own definition to the term or adopt someone else’s definition. But again, that is not what the term means in practice, and it is certainly not the definition Thomas is referring to here.

What Thomas said in this episode/post matches my own experiences and observations of trends among younger generation perfectly. I don’t know Thomas personally, but with all respect due to you, I confess your perspective seems completely out of touch with the reality that I, and apparently Thomas, are living in. (I am going to go out on a limb and say you have no idea who Rhett and Link are and did not look them up when I mentioned them.)

Instead of saying, “Hmm, I don’t agree with this, but Thomas is a friend, so maybe I should look more into this perspective,” your reaction seems to be, “Whoah, Thomas is a friend, but he’s being a complete idiot here.” That does not seem to be either a reasonable or charitable reaction. You can dismiss Thomas’s post. You can dismiss my comments. Or you can dig deeper as I suggested and maybe see that there is support for the perspective that Thomas has presented and with which I agree.

A quick Google search will bring up a list of publicly known Christians who, over the last decade or so, “deconstructed” to a lifestyle of sin and/or atheism. As I mentioned earlier, I can attest to seeing the trend in my own circles. Not once I have heard someone say, “I deconstructed my faith,” and they began living happier, holier lives to God. No, they began living worse, more selfish lives and became worse people. This deconstruction does not lead to a life of spiritual flourishing and eternal life; it leads to a life of sin and spiritual death. Call your experience what you will, but it is not the deconstruction that I know or that Thomas referenced in this episode.

For anyone confused by the comments on deconstruction, check out Another Gospel? by Alisa Childers. Available on Amazon.

It is certainly true that the deconstruction we see going on all around us has some sort of tenuous derivation from Derrida, but the fact is that very people who are deconstructing have ever read Derrida or have any idea what he said. Nor do most people care.

If you want to know what regular people think deconstruction means in practice, take a look at the Wikipedia article on “Faith Deconstruction.” (I can’t believe I’m actually sending someone to a Wikipedia article, but this one does a nice job of saying in simple words what real people mean by the term.) The article gives several examples of definitions of the term, one of which is that deconstruction is about re-examining your religious beliefs. I prefer my definition of “putting away childish things,” but it’s the same basic idea.

Most people who deconstruct are simply reacting to what they perceive to be lies in the church. You can disagree that the church is lying, but the actual people who say they are deconstructing don’t believe one or more of the following claims that they heard in church: 1) That the Bible is inerrant in all its historical and scientific claims, 2) That young-earth creationism is true. 3) That climate change is a “hoax”. 4) That it’s a sin to be LGBTQ. 5) That God favors the Republican policies of taking from the poor to give to the rich. 6) That the genocide stories in the Bible are OK because God said so. 7) That women are in some way inferior to men. 8) And on and on. There are a lot more.

You may argue that none of these claims are taught in the Bible. I would say that some of these have some biblical support, but most don’t. But most people have heard one or more of these claims in church. People deconstruct when they realize that they can no longer believe these sorts of claims, and then they don’t want to have to deal with the church that told them what they consider lies. So they either leave church or they find a church that is more rational. (In my case, I found a church that is more rational. Lots of Christians have done the same. It’s just silly to claim that deconstruction always ends in becoming an agnostic or atheist.)

And contra what Thomas says, very few people reach these conclusions because they watched porn. That’s incredibly offensive, and it really requires an apology from Thomas. Likewise, people don’t start voting Democrat because they watched porn. (Really, Thomas, where do you get these ideas? Why are you so fixated on porn?) People decide that the above sorts of claims they heard in church are false because they got an education and learned how to think critically. People start voting Democrat because they decide that the Republican policies are awful. (I became a Democrat when I watched a Republican debate in 2015 and not one of the candidates could even admit that climate change is real.)

And no, I didn’t call Thomas an idiot. You did. What I have said is that the post (not Thomas) is embarrassingly bad. I’m sure you know how to distinguish between the person and the thing the person writes.

Randy, a few things:

First, I could be wrong, but you seemed to have “nudged the goal posts” in your argument. Your previous comment asserted that faith deconstruction was virtually unrelated to Derrida’s work. Now, it seems you’re maybe admitting to a little more connection but (paraphrasing your sentiment here) “most people don’t know that.” Just so there’s no confusion, I never said the average person was aware of Derrida’s work or connection, only that 1) the connection exists, and 2) it is stronger than what you insinuated.

Second, I never said you called Thomas an idiot, and I certainly did not call him an idiot. Using a rhetorical device that packaged your sentiment in how it came off to me, I said your reaction SEEMED to be dismissing him as an idiot instead of responding charitably in light of your friendship. The most charitable read I can give of your most recent comment to me is that you misunderstood me. However, since I know you’re highly educated and intelligent, it’s hard for me to believe that’s the case; thus, your re-framing of my comment begins to look like malice.

Third, I had read that Wikipedia article already, and the fact that you think it is an accurate and positive portrayal of faith deconstruction is troubling. Also, now that you have presented more about your beliefs and correctly acknowledged what issues serve as deconstruction catalysts for most people, I believe I owe you an apology.

What you have been doing for 60 years probably IS truly deconstructing your faith, and it explains much of what I picked up on in our interactions yesterday:

Throughout your posts, I have seen absolutely zero humility, and the closest thing to charity I’ve seen is your making recommendations to resources that support your perspective. You keep defining deconstruction as “putting away childish things.” If you believe publicly dismissing, chastising, and insulting someone you call a friend are the actions of a spiritually mature adult, you have landed far from the mark for which you claim to be aiming.

The comment I find the most egregious is the parenthetical in your most recent reply: “Really, Thomas, where do you get these ideas? Why are you so fixated on porn?” What is your insulation here, Randy? That Thomas is talking about porn because HE has a porn problem? Do you really not know that porn addiction among young men is rampant and spiritually crippling, and that, yes, pursuit of sexual desire is indeed a common catalyst for, and result of, people rejecting Christianity? If not, once again, you are woefully out of touch with reality. (One of the “deconstructionist” former evangelical millennials I know is now an agnostic in a 4-person polyamorous marriage. But I’m sure that’s unrelated to his deconstruction and that he had never previously looked at porn, right, Randy?) Either way, your insinuation against Thomas is deplorable.

At least, Randy, I don’t think YOUR deconstruction is driven by sex; I think it’s driven by scientism. (Not to be confused with actual science.) You seem like you put much stock in human reasoning, and I know you have a strong scientific background, neither of which are negatives in and of themselves. But you seem to be fixated on things like the age of the earth and climate change. Until now, I have avoided engaging in the more political side of your issues with Thomas’s statement, but I feel compelled to say this:

It is neither rational nor spiritually mature to vote for a party who believes men can become women and that it’s okay for mothers and their doctors to kill babies—living images of God—in utero on the grounds that “the other guys don’t believe in climate change.” (Again, paraphrasing your sentiment here for rhetorical effect, in case there’s any more confusion.) If this is you, your priorities are not based on any Christian view of morality but on the religion of scientism.

And I don’t know. Maybe that argument is lost on you because maybe you’ve deconstructed far enough to think sex is interchangeable and babies aren’t really human until they’ve exited the womb.