The Apostle Paul didn’t write his letter to the Romans—at least not by sitting down alone with paper and ink. He dictated his ideas to an amanuensis, a scribe or secretary who took dictation in shorthand and later rewrote the letter in full. This explains Paul’s conversational yet intricate writing style.

And Paul’s dictation of the book of Romans isn’t some fringe conspiracy theory you’ll only hear in theology school. It’s stated plainly in the text. In Romans 16:22, we even learn the name of Paul’s amanuensis: “I, Tertius, who wrote down this letter, greet you in the Lord.”

At one point while writing Galatians, Paul gets so worked up that he pulls the pen out of his amanuensis’s hand and writes himself, “See what large letters I use as I write to you with my own hand” (Galatians 6:11).

Some Bibles even print that verse in a different font or all caps. It’s possible that Paul wrote the entire book of Galatians himself; and maybe we should read the whole thing in all caps, which, if you’re familiar with Galatians, would actually suit the tone of the book. But it’s more likely that Paul used an amanuensis for Galatians, just as he did for most of his letters. That was the standard practice at the time.

Cicero’s amanuensis was so famous that he now has his own Wikipedia page and is the subject of a popular Robert Harris trilogy. But dictating to an amanuensis didn’t stop with the Roman Empire. John Milton used one. Mark Twain experimented with it in the 1800s. G.A. Henty, my favorite Victorian YA author, used dictation extensively. The list goes on: Jules Verne, Agatha Christie, Winston Churchill, and Dan Brown all used dictation to write their popular novels.

Why was dictation so popular?

It was simply faster. Most people speak at 120 to 150 words per minute but type only about 70 words per minute. Writing by hand, whether in cursive or print, is even slower.

By contrast, a trained amanuensis can take shorthand at up to 150 words per minute, the same speed as typing. So why did dictation fall out of favor in the second half of the 20th century?

Because we stopped teaching shorthand in schools.

Shorthand is far more useful than cursive in almost every context. If you’re a Baby Boomer lamenting that kids can’t read cursive, remember that you can’t read shorthand, which was actually more practical. We’ve already eliminated the most useful of the three major English writing systems.

Now, I’m not sure who made the decision to phase out shorthand; but I’ve heard that gender politics may have played a role.

If you want to make a living as an author, it helps to write quickly. The faster you write, the more books you can publish and the more income you can generate. It takes a lot of effort to improve your typing speed. You have to ask yourself if it’s even worth it, considering you can already speak twice as fast as you type.

Dictation went through a dark age in the late 20th century when we lost the ability to write shorthand and had nothing to replace it. In fact, many people today don’t even know what shorthand is; they’ve only heard the word.

Eventually, though, computers began to understand speech. The technology was clunky at first. You had to say “comma” every time you wanted punctuation. But today, talking to a computer is just as accurate as dictating to an amanuensis 2,000 years ago. We’ve finally been able to recreate the technology of Tertius.

And yet, most authors are still pecking away at their keyboards instead of dictating to a digital amanuensis. This slows their output and limits their income.

How can you leverage the ancient power of dictation to boost your writing speed?

I asked author Misty M. Beller, who’s used dictation to help her become a USA Today bestselling author. She’s written over 45 historical romances and sold more than 1 million books.

How did you get started using dictation?

Thomas: How do you use dictation? How did you get started with it?

Misty: I wrote my first 20 or so books by typing, just like most other authors. I wanted to get faster. Even though I could type around 100 words per minute, I wanted to write as fast as the ideas were coming into my head.

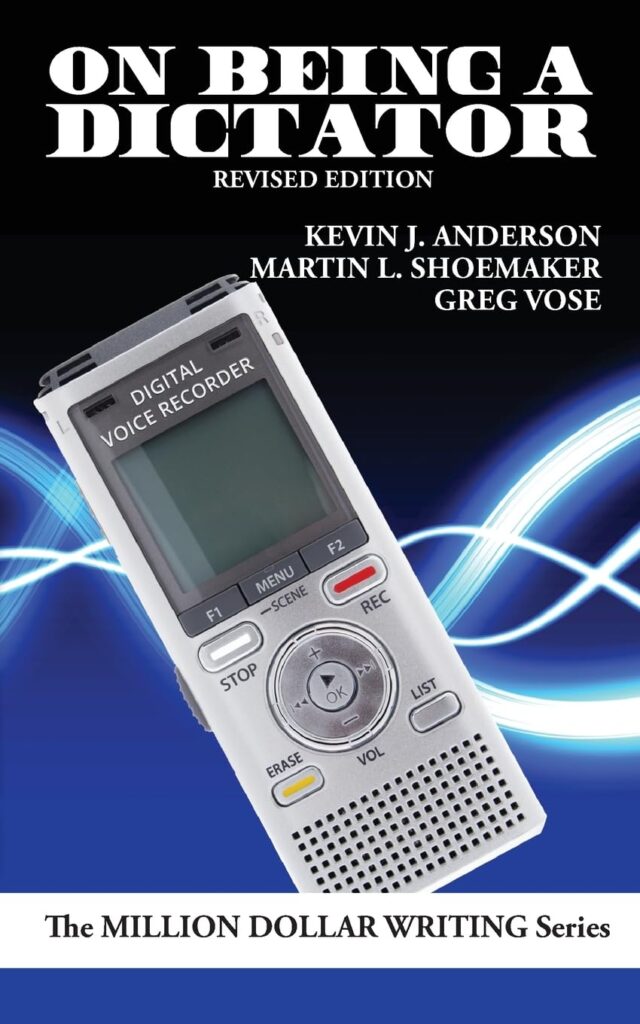

Then, I heard a podcast that intrigued me. It featured Kevin J. Anderson talking about a book he had written called On Being a Dictator (affiliate link).

It was fascinating to hear how he used dictation to write his books. He would hike a mountain trail and dictate chapters or head to the beach and do the same. That sounded amazing to me, so I decided, I can do this. I’m going to learn it. And the rest is history.

What software do you use for dictation?

Misty: I started when Dragon was the most advanced dictation software. Specifically, I used Dragon Anywhere, which is a mobile app for iPhones. In the book, they actually talked about using a Walkman you could carry around that didn’t require Wi-Fi. I think that’s what Kevin used at the time because he could just record onto a tape and then send it to a transcription service.

Thomas: So he was using an amanuensis in the old form.

Misty: He was. But I liked Dragon Anywhere. I still use it because I’ve trained it to recognize my voice. I love that it adapts. I can input words and train it on how I say them so that when I speak, it knows the correct spelling.

Thomas: If I have a world filled with Elven place names and Dwarven cities, I can teach it how I say “Alethkar,” and it will spell it correctly every time?

Misty: Exactly. The series I was writing at the time had a lot of Native American names, and those are rarely spelled how they sound. But in my head, I had to pronounce the names the way the characters would.

Do you have to speak the punctuation?

Thomas: One of my frustrations with Dragon was that it didn’t handle punctuation very well. Has it gotten better, or do you still have to speak the punctuation?

Misty: Honestly, I don’t know. I’ve done it for so long that I speak the punctuation automatically. Even when I’m dictating a text on my iPhone, I can’t help it.

Thomas: For those of you thinking, That’s a deal breaker. I could never say “period” or “comma” out loud, don’t worry. All the modern tools can handle punctuation automatically.

You don’t even have to pay for software anymore. The built-in Mac transcription tool is so good. It’s better than Dragon was five years ago. In fact, it might be better than Dragon now, especially if Dragon still makes you speak the punctuation. It’s quite advanced.

There’s also built-in dictation on your phone. You can pull up the Pages app and dictate directly into it. You don’t need Dragon anymore. A lot of old-school authors still use it because it works for them, and they’re used to it. But if the price of Dragon is a barrier for you, don’t worry. OpenAI released an open-source dictation engine a couple of years ago that anyone can use for free. There are many ways to do dictation very cheaply or for free.

Misty: One of the old challenges with dictation was that it would insert the wrong word, especially homophones. That was the biggest problem. Sometimes, it would just mishear or mistype a word entirely. It’s still an issue with homophones.

Thomas: That’s not as much of a problem with the new AI engines. They understand your words, context, and sentence structure. The homophone issue is greatly reduced. We dictate every one of these podcast episodes to create the blog post versions, and while it occasionally messes up names (I’m sure it got “amanuensis” wrong), we rarely have trouble with normal words.

Misty: The workaround for a while was to drop the transcription into ChatGPT with some prompts. It would clean it up and add paragraph breaks. It’s a beautiful thing.

The cleanup process used to slow me down and was more painful than anything. But I could dictate so much faster than I could type.

Eventually, I decided I needed to buy some time back. I asked my virtual assistant if she’d be willing to clean up my dictation. It was a little unnerving having someone else see the first draft before I even looked at it, but it worked.

Thomas: I’ve found that you can actually use ChatGPT for this first pass if you’re using the paid version. My assistant, Shauna, uses a lot of AI tools to “blogify” our episodes. She acts as an AI-augmented amanuensis.

The prompt we found that works well is, “Rewrite this section with clarity and preserve the original wording as much as possible.”

That prompt helps ChatGPT fix the commas, periods, and paragraph breaks without changing the voice or meaning. It works especially well for conversations like this, where we’re not always speaking in full sentences or inserting punctuation manually. We’re just talking freely. AI is good at shaping our free-flowing conversation into traditional sentence structure without losing the meaning or much of the original wording. That’s exactly what an amanuensis used to do.

The amanuensis would add some clarity by taking the shorthand version and converting it to a full, word-for-word transcription. Some human cognitive effort is still involved. It’s not just about capturing words; it’s more of a thought-for-thought rendering of what was originally said.

Misty: I love that. It’s like an editor cleaning up your work.

Thomas: If the amanuensis is good, it absolutely is. It’s like working with an editor; but the editor is working on your raw stream of consciousness, straight from your mind, rather than something you’ve already edited.

When writing on a keyboard, there’s a tendency to be more deliberate, even plodding. That has some advantages, but the big disadvantage is that it’s slow.

Since most people use Word or Scrivener to write and edit, there’s a massive temptation to spend all your time editing. That shifts you into a critical mode of thinking, rather than a creative one. Most people can’t be in both modes at the same time.

Misty: It was definitely a challenge to get out of my own head when I first started dictating. But Kevin J. Anderson’s book really helped me ease into it. Rather than jumping straight into dictating the next chapter of your book, he suggests starting with brainstorming. Just speak into your device in a stream-of-consciousness style. That made a big difference for me.

Do you create an outline before you start dictating?

Thomas: When you’re dictating, are you working from an outline, or are you flying by the seat of your pants?

Misty: I’m not a discovery writer or pantser, so I always create an outline. It helps with dictation. If I don’t have one, I wander down too many rabbit trails. I started typing out my chapter outline during the plotting phase of the book, then printing it off and taking it with me. I walk when I dictate. I glance at the printed outline as I walk and talk, and it helps me stay on track and avoid straying too far into character conversations.

Where do you do your dictation?

Thomas: Let’s talk about this walking and talking. You’re not the only author I’ve heard who does this, and it seems like a fun way to write a book. Where are you when you write?

Misty: When I first started dictating, I’d just walk through the neighborhood. Kevin talked about hiking trails and walking on the beach, which sounded amazing; but I just walked the neighborhood. I joked that you could always tell when I was writing a book because I’d be skinnier and tanner from walking outside for hours. However, walking benefited my brain and spurred my creativity.

I swore by it for years. Then I read a Stanford study that showed our brains are 60% more creative when we’re walking. They say that effect applies indoors or outdoors; but, for me, it’s not the same. I prefer walking outdoors. On rainy days, I’ll sometimes carry an umbrella and walk outside anyway. If I try to pace across the living room, it isn’t nearly as fun or effective.

Thomas: Walking on a treadmill doesn’t feel nearly as inspiring as walking through the woods.

Misty: If the study showed that you get the same creative boost walking indoors or outdoors, I’ve wondered if maybe it’s the beauty of God’s creation that adds additional inspiration. Maybe it doesn’t directly impact creativity but affects mood or something else. There’s just something extra about being outdoors.

Thomas: The ancients had incredible memories. It was common for Greeks to memorize the entire Iliad or Odyssey and for Jews to memorize the entire Torah. Now, we can’t even remember a phone number. Part of the reason is that we’ve changed how we use our brains.

They used to associate memories with physical locations. They’d visualize a room or a temple and mentally “walk” through it, placing memories in different drawers or areas. Religious temples often served as real-world memory aids.

For those familiar with computers, it’s like using a GPU instead of a CPU. The brain processes visual content far faster than auditory content. When choosing a stock photo, you can scroll through hundreds quickly. But if you’re choosing stock music, you have to listen to each song, which takes far more time and effort.

You can’t listen to a dozen audio tracks at once, but you can look at a dozen images at once. So when you’re walking, you’re storing memories in the visual, physical environment. A tree or a building can become memory anchors. You’ve probably experienced returning to a place you haven’t visited in years and, suddenly, memories come flooding back. They’re stored in your brain’s visual processing area.

That’s why I doubt Stanford’s claim that treadmill walking is just as effective. Sure, you get cardiovascular benefits and more blood to your brain, but I think there’s a bigger benefit to moving through nature while telling your story.

Misty: You’re talking about stimulating all the senses. Being outdoors is being in a temple of sorts. That would absolutely create multiple layers of memory, not just cognitive.

Thomas: It’s just a theory! Our listeners can feel free to debunk me in the comments. Go to christianpublishingshow.com, scroll down, and tell me why I’m wrong.

Misty: Speaking of theories, I wonder if all those fabulous authors in history stopped using dictation because authors don’t make much money and they couldn’t afford it. For a long time, dictating meant paying someone unless you had a very patient spouse.

Thomas: In the old days, most authors were aristocrats. Then came the typewriter, which democratized writing and made it accessible to the middle class. While the average author couldn’t afford an amanuensis, they could buy a typewriter. But they couldn’t hire a clerk or secretary until they had some success.

Mark Twain didn’t dictate his earlier works. He started experimenting with dictation only after he had money.

You already own a phone dictation capability that rivals what you would’ve had to pay for just five years ago. We’ve democratized dictation. You’d think that would be a huge deal, but no one is talking about it. Apple rolled out a powerful new text-to-speech engine, and all anyone could talk about was the slightly better camera.

Misty: The ability to dictate your books is now literally in your own hands.

How do you capture the audio with your phone?

Thomas: You start at your computer, typing out the outline. Then you go walk in nature and get lost in telling the story. How are you capturing the audio on your phone?

Misty: I just hold my phone upside down so I can speak directly into the microphone, and I stroll. For me, learning to dictate required taking the pressure off. Our neighborhood at the time was very quiet. Now we’ve moved back to the family farm, way out in the country. I just walk up and down our quarter-mile-long driveway. That way, I’m not worried about people staring at me or judging me for talking to no one.

Thomas: You might try using AirPods. That way, your arms are free to swing while you walk, and you won’t get a crick in your elbow from holding your phone up.

AirPods are those little wireless earbuds that fit in your ears and have built-in microphones. They’re surprisingly good at capturing audio as long as you keep them clean. It could simplify your process a bit.

If you get noise-canceling AirPods, they might do a better job filtering out ambient sounds. I’m not completely sure about the audio processing, but I’d guess they’re better at it because they already have engines for isolating sound. Noise-canceling works using negative and positive sound waves that literally cancel out the background noise.

What do you do with the rough transcript of your dictation?

Misty: First, I copy and paste it into a Google Doc. I like having it saved somewhere besides Dragon. There’s a little feature in Dragon where you can accidentally “select all” by voice and delete everything, which is a huge bummer. Often, you can tell it to paste the text back in, but there have been a couple of times that didn’t work.

Thomas: For the record, I don’t like Dragon. I feel like every other solution is better. I know the old-school folks swear by it, but these kinds of issues are scary for someone new to dictation. The built-in AI dictation on your phone doesn’t listen for commands the same way and won’t nuke your entire manuscript.

Misty: It’s just that Dragon is so well-trained to my voice. It knows my Southern accent and all the unique character names I use. I might try something else eventually; but for now, my process works pretty well.

After pasting it into a Google Doc, I put it into ChatGPT 4.5 through Poe, which is an aggregator of different AI engines. I give it a simple command that cleans up homophones and adds paragraph breaks.

Thomas: Right now, we get new versions of AI every few months. Interestingly, some say 4.1 outperforms 4.5 in certain cases.

Sam Altman has said they’ll fix the naming system eventually; but for now, it’s chaotic. The important thing is to use the paid models. A lot of people think AI is worthless because they’ve only tried the free versions, and they’re not very good.

Using Poe, Reka, T3 Chat, or just paying for ChatGPT directly will give you access to the good models. If you’re using a free model, the only decent ones are Grok by Elon Musk and the latest Gemini from Google. Gemini is powerful but also very biased. It’s the “wokest” of the free options. Still, it’s smart.

In general, I recommend being a customer. Pay for what you use.

After you paste it into GPT for a light cleanup, what do you do next?

Misty: Then I move it into Word. If I’m on top of things, I try to do my read-throughs in the evening or late afternoon and do my fresh writing in the mornings. But I usually fall behind after the first few chapters.

I write full-time. This is how we support our family. I usually release four to six books per year, so I’m always writing. Now that I’ve added the ChatGPT pass to catch typos and formatting issues, I usually do only one full read-through before sending the manuscript to my editor.

This is my 49th book. It wasn’t always my process, but it’s where I’ve landed.

Thomas: Some people may be shocked to hear you write six books a year. But with dictation, that’s very feasible. Some authors can type 70 words per minute, but most people type closer to 30 to 40 words per minute. When you’re writing a novel, you tend to pause, think, and self-edit constantly. Every time you touch the mouse to fix a word, your words-per-minute rate drops.

Dictating without watching the words appear creates a healthy separation between creating and critiquing. You’re out in nature, in creation, telling your story. Later, you sit down with coffee and begin editing. It’s a different mindset.

Misty: I tried dictating at my computer, but I couldn’t do it. Watching the words slowly appear on the screen made me want to fix every mistake in the moment. Getting away from the screen changed everything.

Another big help was learning to give myself grace. We’re not born knowing how to type efficiently or dictate well. Both are learned skills.

Even now, I speak slowly when I dictate. It’s not a rapid-fire monologue. I speak a few words at a time, then finish the sentence. I let it come as my brain sees the image and chooses how to describe it. Giving myself grace and learning to enjoy the process keeps me from burning out.

Thomas: If you’ve been typing for 30 years and dictating for 10 minutes, it’s not going to be as polished. You have to give yourself time to learn this new technique.

That said, some people do pick it up quickly. If you type with two fingers, you might be better at dictation within 15 minutes. But most of us have years of typing experience. So, yes, dictation comes with friction; but it’s a skill worth building.

Don’t let anyone tell you it’s not “real writing.” I opened with the Apostle Paul because if dictation was good enough for him, it’s good enough for you. Mark Twain, Agatha Christie, John Milton, and Cicero were real writers, and they dictated.

Misty: One interesting side effect of dictation is that I naturally slipped into a deeper point of view. I could get into my characters’ heads. I had to scale back the internal monologue to keep the story moving. But that depth was a neat discovery.

Thomas: I’ve experienced that too. Between the Christian Publishing Show and the Novel Marketing podcast, we publish over 200,000 words a year from the podcast transcripts becoming blog posts. Shauna helps a lot with editing those. But that’s a million words over the past 10 years, and they flow so much more naturally because they start with talking.

You’ve been typing for 30 years, but you’ve been talking even longer. Once you connect your storytelling to the skill of speaking, dictation becomes much easier to unlock.

If you’re a parent who tells your kids bedtime stories, you’ve already been doing this. Telling stories aloud is one of the oldest forms of storytelling. Your voice can carry beautifully into your written work.

Misty: Yes! Every writer has their own voice. It might feel different when dictating compared to typing, and that’s okay. Give yourself grace. It’s a learning process; but the more you do it, the more grateful you’ll be that you tried. Plus, you’ll get your steps in for the day, which is a huge bonus. Our bodies are one of our best assets as writers.

Thomas: That’s one downside of podcasting. I feel like I have to be in the studio, so I don’t get my steps in. But writing outside is fantastic, especially for fiction. Most novels take place outdoors, especially in fantasy, unless you’re writing sci-fi in a spaceship.

Being in nature while writing about nature gives you a stronger sense of groundedness.

Misty: Most of my books take place in the Rocky Mountains during the frontier era. Sure, some scenes are inside a log cabin, but most happen outdoors. I’d be out there sweating while writing about a snowstorm, but I was still experiencing nature; and that mattered.

What advice do you have for a writer who wants to try dictation?

Misty: Start with something easy and free. Try the built-in dictation on your iPhone or Android. If that doesn’t work well for you, try something else. There are so many apps and resources out there. I’ve heard great things about Otter.ai.

Try Dragon Anywhere if you’ve tested several free tools and still haven’t found one that captures your accent or voice and transcribes it accurately.

Thomas: We also post deals on our deals board at AuthorMedia.social. It’s a special social network just for authors, and it’s free to join. When I find discounts on software or services, I share them there.

Occasionally, new transcription tools offer lifetime access for something like $50 because they’re trying to acquire users. These AI transcription tools are impressive. They’re combining what you are now doing in two steps. For example, they’ll transcribe and correct homophones in real-time, using AI to understand the sentence the way a human would.

They transcribe the audio and use context to make sense of it, similar to how we naturally understand what someone means, even if they mispronounce or mix up words. These tools are starting to do that.

Misty: I’d also encourage writers to experiment with different tech. Try various tools or microphones until you find something that works for you.

I’d also recommend starting with brainstorming instead of prose. There’s something intimidating about hearing yourself talk out loud. Break that barrier with something low stakes. It’s okay to ramble. The goal is to get comfortable with your voice. Once you do that, you can gradually move into dictating prose.

Thomas: Here’s a tip for nonfiction writers, especially those of you who are speakers. If you’ve been giving speeches for years and are now thinking about writing a nonfiction book, try creating a “speech” for each chapter. Instead of trying to learn how to write a book, start by writing a speech. Then, deliver that speech to a real audience, like a small group of local people who are interested in your topic. Let them know it’s part of your writing process.

Once you give the speech, you’ve got a chapter’s worth of material. Record it, transcribe it, and now you have something to edit. You can build a book quickly by using the skills you already have.

If you’re unsure whether that method “counts,” remember that’s how Jesus delivered the Gospels. He spoke, and others recorded His words. All those red letters in the Bible come from someone transcribing His speeches.

So don’t tell yourself it isn’t a valid method. If it was good enough for the Son of God, it’s good enough for you. Dictation is a completely legitimate way to write your book.

Misty: For those of you who give speeches, you’ve probably wanted to go back and edit what you said. This is your chance to go back and edit.

Thomas: Exactly. If you give a speech and the audience is ready to push you off a cliff, that might be a sign you need to rethink that section. Although Jesus kept those parts in. He told the truth, even when people didn’t want to hear it.

Misty: Yes. And they did try to push Him off a cliff.

Thomas: However badly your speech went, it probably didn’t go that badly.

Which of your books would you recommend to someone who’s never read your work before?

Misty: I know I’m supposed to say the most recent one, but I’m going to go with the book that has sold the best and that readers have absolutely loved. It’s The Lady and the Mountain Man (affiliate link). It was the second book I wrote, but it was the one that launched my career.

Connect with Misty

Featured Patron

If you are a Christian author who writes fantasy and science fiction, you must discover Realm Makers Writers Conference and Expo. Learn from the top leaders in the industry. Pitch your manuscript to agents and editors in both the Christian and general markets.

Find your tribe.

Hone your craft.

Advance your career.

Visit realmmakers.com for complete details.

I can speak a quatrain to the sky,

but never more than that;

for poetry, it seems AI

ain’t the way to skin a cat

because I have to see each word

in more than just a walking-dream

so that I might point them toward

their place within the rhyming-scheme,

but if I still wrote prose-y stuff

I’d love to do it with dictation,

although it might be kinda tough

given my situation

in which AI might really goof

on hearing Peanut’s Great Dane WOOF!

If anyone’s interested, Dragon Anywhere has a subscription cost of $15/month (or $150/year), with a one-week free trial. It’s from a company called Nuance, and they have legal and medical versions ($65/month) for those who might want to follow in the footsteps of John Grisham or Robin Cook.

I don’t get any kickbacks from Nuance. It’s just that it’s too painful to sleep, to early to start getting the dogs out, and besides, dragons are cool, as is today’s post.

I always find posts on dictation fascinating, however it’s never really worked or been productive for me. I need a keyboard to organize and iterate my thoughts as an ADHD/Aspergers Syndrome neurodivergent and I can probably write FAR more coherently than I talk. Talking, I tend to stumble over words or go off on rabbit trails, while with the keyboard its easier to streamline and while yes, I can talk faster than I can type, I’m a decently fast typist and for my easily-distractable/has trouble with verbal explanation brain, keyboards are better XP.

Really wish it did work for me though, sometimes I see these “write faster with this trick!” articles and its just… use dictation… and I’m over here like “BUT WHAT IF THAT DOESN’T WORK?” and there are no answers…

Sorry, I still believe in longhand, though I am intrigued by dictation as one walks. Right now I use my iPhone as Iwalk to jot down ideas to insert with my latest book (nothing published, so I am impressed by 50 books.)

My historical fiction also requires as much research as it does writing, thus much of my reminders on my iPhone are research reminders.

This was a very insightful and informative article. I typically use dictation for quick notes, to-do lists, and occasionally to capture thoughts related to my writing. Although I write non-fiction, this has inspired me to incorporate dictation more intentionally. Thank you both for sharing your perspectives—I’m looking forward to dictating more (and not just to other people)! 🙂

Dictation has been a wonderful tool for me. I dictate ideas straight into Google docs, while walking on my treadmill. I’ve learned that if I don’t get it on “paper” right away, the ideas can get lost in my older head. The treadmill is one of my favorite places to pray and think. Sometimes, I can distill an idea better even with my eyes closed, which is possible while walking on a treadmill.

But…this article opens up new possibilities for better dictation apps and pushing into some pretty nature walks. Thank you.

Thank you for the information. I just finished a workshop called Dictation Bootcamp & like the idea of dictating my stories.

However, can you please address the caveats to using any AI for our dictated writing, both fiction and non-fiction.

I’ve seen fiction contest rules reject AI modified entries. How they treat simple punctuation fixes vs. rephrasing & rewriting, I’m unsure. ProWritingAid will point out punctuation, style, & grammar errors. They also offer to rewrite it for you. How do publishers react to AI modified stories?

Non-fiction articles may not be accepted if AI modified or enhanced. My husband has seen this in his field of psychology.

Both represent restrictions due to AI modified writing being treated as not original work.

How do we avoid these rejections? How do we keep AI from becoming our voice? Holding the line takes thoughtful consideration.

Those concerns aside, marching around the mall dictating my story when it’s 108 degrees in AZ is my goal. 🙂

All the best,

Karen