The path to publishing success is rarely smooth and easy. There are bumps and bruises along the way. Writing requires hard work, some sleepless nights, and sometimes heart-wrenching disappointments.

But there’s also so much God-given joy in the successes as well as the failures.

As we walk this journey, hearing from authors who are farther up the path is a huge encouragement. They can tell us what’s ahead and help us learn from their mistakes and victories.

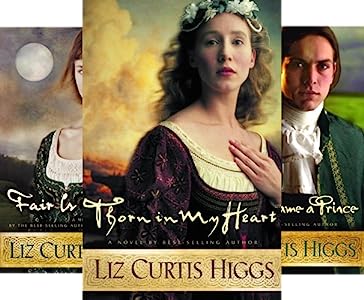

I recently interviewed long-time Christian speaker and author Liz Curtis Higgs, who’s experienced many highs and lows on her publishing journey. She’s the author of 37 books, including Bad Girls of the Bible, which has sold over a million copies. She’s spoken at over 1,800 conferences in all 50 states and in 15 countries.

Liz Curtis Higgs: I have had a few bumps and lumps, and I’m happy to talk about them because the truth is we don’t usually learn from people who “do it right.” We learn from the mistakes they make. Although I’ll be honest, I still have to make the mistakes myself. I could sit and listen to a pro who’s been out there longer than me, and I’d nod and take notes, but then I’d go make my own mistakes.

My dad often told me when I was growing up, “Success is a poor teacher.”

How did Liz Curtis Higgs get started writing?

Thomas Umstattd, Jr.: So, how did you get started in writing?

Liz: I was a radio personality for ten years, and about halfway through that career, I met Jesus, and it changed everything. It didn’t change the station I was working on. It just changed the woman who was at the station. People always laughed and said, “Liz, it became Christian radio the minute you became a Christian.” And it was true.

I was blessed to work at places that let me talk gently about my faith and interview people like Amy Grant. It kind of changed the show, if not the station.

I had a wild and woolly testimony, and in November of 1982, I was asked to share my testimony at my church.

I was scared to death. I didn’t eat for three days before the speech.

I was used to being behind the microphone in a studio where nobody was looking at me. It didn’t matter how I was dressed or whether I had makeup on. But suddenly, I was going to stand in front of my church of 500 people who knew me and thought I was basically a good girl.

I shared a seven-minute speech, and I told my whole guts-to-glory story. People laughed and cried and then stood up at the end.

That was my first time to speak publicly and share my testimony. I went shaking back to my seat, and my pastor said, “Liz, I think this is what God has for you.”

I said, “No way, baby. I haven’t eaten in three days. This is not how we’re going to do this.”

But my pastor was right. Five people who were not from our church were there, and they asked if I would share my story at their churches.

So, I began to speak. I was still in radio full-time, but I was also speaking when I could. Churches started to invite me back, but I only had one testimony, and I knew I couldn’t tell the same story, so I began to develop material as a speaker.

By 1987, I was speaking 90 times per year, still doing full-time radio, and I’d had my first child. Something had to go, so I said goodbye to radio after ten blessed years. It was nuts because it was my full-time job, and I was the primary breadwinner. But with 90 presentations that year, I had only made a total of $5,000.

Leaving radio was a scary leap of faith. But I felt strongly called to become a speaker. Of course, I was a mom too, and I could arrange my speaking around my mothering. The kids often went with me, so it worked great.

Thomas: And this all happened before you wrote a single book.

I want to point out that there are two kinds of authors: speakers who write and writers who speak.

Someone who practices on stage for five years, honing their stories, is a speaker who writes. The advantage of being a speaker who writes is that you get to test your material to see if your jokes are funny and if your stories make sense. If you get questions at the end about something everybody misunderstood, you can clarify that point the next time you speak.

The writer who speaks spends more time revising their books with editors. It’s a different process, but there’s more than one path to publishing success.

Liz: For many years, I thought of myself only as a speaker who writes, but there was a shift down the road.

By 1992, I was giving about 120 big presentations per year and finally making some serious money, which was a blessing. I was primarily speaking in secular settings to some associations, schools, health care environments, and churches, but mostly big arenas for big groups.

Besides your testimony, what did you speak about?

Thomas: What topics were you speaking about in those secular settings? I imagine it wasn’t just your testimony.

Liz: Not at all. In fact, I had to sneak the testimony in, and I found lots of fun ways to do that.

I would say to an audience, “The woman standing before you today used to be quite a different person. In fact, I worked with Howard Stern, who told me to clean up my act.”

Now that will get an audience’s attention if they’re at all familiar with Howard Stern. That line would make them lean in and want to know more. It opened the door.

In churches, I was very open about my faith and teaching the word, but in secular settings, I was called a “motivational humorist.” I brought motivation, which often segues to inspiration, which can segue into scripture. Plus, I was funny, and humor tears down a lot of walls of resistance. Funny stories make people feel relaxed.

A bright woman once told me, “The audience feels what you feel. If you feel relaxed, they do too.” It’s true for writing and speaking.

When you’re relaxed in your writing voice, when you aren’t trying to impress or get out of your area of knowledge, when you stick with what you know, and you share it honestly, your reader relaxes too and lets you in.

Thomas: I like to define “voice “as how you write when you’re not scared or afraid of criticism.

Finding your voice is the same as finding the courage to say what you actually think and put it on the table.

Liz: Yes. I had to find that voice on the platform, which made it easier to segue into that voice on the page. In fact, people always say, “You write just like you speak,” and that was my goal.

Eventually, a publisher heard me speak and said, “Do you mean to tell me you’re speaking to 120 groups per year, and you have no book in the back of the room to sell?”

I said, “Well, I’m working on one.”

I sent it to them, and they said, “That’s great. We’ll take that one and two more.”

I’m embarrassed to share that story at writers conferences because it makes it sound so easy, and it’s not how publishing contracts typically happen.

Thomas: But it wasn’t easy. You spent ten years building a platform, which was a speaking platform. For someone with a large platform, getting a publishing contract is “that easy” in the sense that publishers know they can break even on an author with a big platform regardless of whether the speaker can write.

In fact, if your platform is big enough, a publisher will pair you with someone who can write. For example, if you’re the Prince of England, they’ll make it work.

Liz: I was an English major in college, so I was a writer, but I was not a published writer.

Early on, the publisher offered to pair me with a real writer, but I had some writing abilities and some knowledge of how to put words together, so I declined. I knew I couldn’t stand in front of an audience and talk about a book I didn’t write. I can’t possibly do that. The ethics don’t work for me.

Now, having said that I know there are Christian authors who have cowriters and ghostwriters, and I’m not making a judgment on that. I’m just telling you where I was coming from. I could not have slept at night if I had anybody else write my books. I’m super grateful for the input of a great editor, and I’m happy to make recommended changes, but I wanted to write my own books from my heart with my voice on the page.

God, in his goodness, made me a speaker first so that I could bring the expertise and platform to the writing. Remember, this all happened way before social media. I didn’t even have email. I had to send manuscripts on floppy disks!

Thomas: The original form of platform was speaking from a stage. Email, websites, and social media are relatively new tools for authors. But public speaking from a stage has been practiced for centuries. Even Mark Twain went on a speaking tour in the 1870s to promote his book.

Liz: In my case, I didn’t do public speaking to sell books. I did it to encourage an audience. But as people would ask, “Do you have this in book form?” I figured I needed to offer that.

When Thomas Nelson came to me and said, “We’ll take this book and two more,” that’s when I understood, “Oh my word, it’s because I’m a speaker, not because I’m a writer. They don’t even know if I’m a writer yet. They haven’t read the first page of what I’ve been writing.”

It was a little scary, so I immediately realized I better get better at writing. I started attending writers conferences immediately to improve as a writer and to get serious about writing.

I spoke and wrote for many years, but a shift happened around 2000 when I realized I was a writer who spoke.

Around that time, Bad Girls of the Bible was selling like crazy. All my books did well, but that one was crazy and is still my bestseller. All the other books that came before were drawn from my messages. I gave my speech on the platform first, and then it became a book.

But Bad Girls of the Bible was the first nonfiction book I wrote that began as a book and not a speech.

How did you turn a speaking message into a book?

Thomas: Obviously, you didn’t record your spoken message and hand the transcript to an editor. How did you turn a speaking message into a book?

Liz: I almost never write out a transcript of a message. In fact, the worst speech I ever gave was from a written transcript. I was being paid $500, which seemed like so much money. At previous events, I was paid $25 and a chicken dinner. I figured this speech better be amazing, so I wrote out every word.

I was a nervous wreck because of the money. I read the speech, and it was horrid. I’m lucky I ever got another booking after that one.

Since then, I only ever work with bullet point notes when I speak. However, when I’m practicing at home, I fill in the bullet points so I do have a mental transcript.

The difference between speaking content for a three-hour retreat and a whole book is that there’s no audience talking back to you. It’s just you and the words.

From my spoken message, I would first create a table of contents. If you can’t mine from your speech ten content-rich chapter topics, you probably don’t have the content to fill a book.

Thomas: A good table of contents is a marketing tool. Potential nonfiction readers turn to the table of contents to make their buying decisions. Your chapter titles should pique the potential reader’s curiosity and make them want to read the chapter.

Starting by writing the table of contents is a solid strategy for nonfiction writers. The table of contents will even drive the marketing copy around the promises you make to your reader in your back cover copy.

If people aren’t excited about your table of contents, they’re not going to be excited about your book.

Liz: Chapter titles let a reader know whether your book is fun, deep, or practical, but first, you must determine whether you have content people are interested in.

Sometimes a chapter title also will give you your book title. You might write one and realize it’s overarching and would make a great book title.

I had a message titled, One Size Fits All and Other Fables, and it became my first book.

If you have a killer title for your speech, a publisher will probably let you keep it for your book because you’re already speaking on it, marketing it, and promoting it. You already have audiences looking for that title. That was my secret to getting to keep my book titles.

Thomas: Your title was also market tested. If you send your list of three speaking titles to event planners, and they all pick the same one, you can know that title (and topic) resonates.

A savvy publisher will recognize that as a market-tested title, and they won’t want to mess with it. But a clever market-tested title is different than a clever title based on a phrase your mother said when you were a child. Just because it means something to you doesn’t mean it’s meaningful to your reader.

Liz: You only need to present the event planner with three topics or titles. Three is the magic number. You can’t offer a particular audience or meeting planner more than three. It boggles their mind. It’s too many. Plus, it means you’re getting very scattered. An event planner wants to see you as an expert in one thing and not just a speaker who has a ton of topics. You need to look like a person who has one great message to share and two messages that grew from it.

I think that’s why Thomas Nelson said, “We’ll take that book and two more.” I had three topics that I spoke on, and the next two books were indeed my next two messages that I shared from the platform turned into books.

Thomas: I imagine the writing goes quickly because you’ve already worked through words and phrases in spoken form. The first draft starts out like the speech, but as you revise it, you add stories, anecdotes, and scripture to bulk it up and reinforce your points.

That process is different from traditional book revisions, where you subtract unnecessary words and phrases.

Also, when you give a speech, it’s a little different each time you present it. Jesus told a story about a rich man who went to a faraway country, and all his servants stayed home and invested his money. We know he gave that speech a lot because the different gospels record slightly different versions.

As a speaker, you may switch things up within a speech to keep it interesting and personalize it for your audience. You might swap out your examples based on your audience, and with several different versions of your hour-long talk, you may have three hours of content to draw from when you begin writing the book version.

Liz: You’re bringing in other voices, such as books you’ve read and scripture. I never wanted to feel like I was bulking it up to hit a word count, but you do want to enhance the book so that it’s worthwhile.

How long is the average nonfiction book?

Thomas: For print-on-demand, the sweet spot is between 200 and 250 pages. The cost of the book scales linearly with the number of pages. More pages mean higher production costs. And additional pages don’t increase the sales price enough to justify the costs of print on demand.

Many publishers rely on print on demand, especially for beginning authors. Don’t pitch a 300-page nonfiction book. Shoot for 200 pages for your first nonfiction book. If you have more to say, write another book.

Liz: When I wrote Bad Girls of the Bible, I had twice as much material as I needed for the first book. The first book was about 300 pages, and I covered the stories of 10 women from the Bible. I was writing about the next 10 when they told me to stop because the book was long enough. They said if the first book did well, then I could write the next 10. Well, the first book did well, so I wrote the second book, Really Bad Girls of the Bible

Today, less is truly more, especially in nonfiction. Fiction is another story.

Thomas: This is fascinating because you went through a transformation. You began as a speaker who writes, starting with audience-tested material, which feels safe because you know that it works. Then you switched to a totally different approach and began your book with a blank page.

How did you write Bad Girls of the Bible as a writer who speaks?

Liz: Once I learned to write a book from scratch, I wrote every book that way.

I always start with scripture, telling a story that’s in the Bible. That was a big shift. I wasn’t doing topical books where you write your book and then find scripture to support your point.

I start with scripture, and I put that section or passage onto the screen. I’ll look at it in 60 different English translations to look for nuances. Then I examine my own heart and pray over the page. I say, “Lord, what does this scripture say, and what does it make me think? What questions does it make me ask? How does it challenge my faith?”

I look at one verse, one phrase, or one word. I’m no longer a speaker, but I am a teacher, and I love to camp on one word at a time. I taught Ephesians for ten months. Do you know what the first word of Ephesians is? Paul. In the first week of class, all I taught was “Paul.” That’s all I covered. The second week, I got to the next words, “an apostle,” and I taught on that for an hour.

No publisher would want to touch what I’m doing now. I just, I love to break it down. My son calls it a slow roll.

Being a teacher is entirely different than being a speaker. A speaker gets one shot. You’ve got 40 minutes to get the audience on their feet, either literally or emotionally, by the time you’re done.

Teaching is a whole different story.

Thomas: Benjamin Franklin wondered why George Whitefield was so much better than his local pastor. In his biography, Franklin ponders it and realizes that Whitefield gave the same talk to a new audience multiple times a day for months, and every turn of phrase was practiced and polished.

By contrast, his local pastor had to create a new talk every Sunday. He realized it wasn’t fair to compare Whitfield’s one polished talk with his pastor’s 52 new talks every year.

Some mediums lend themselves to different kinds of messages. A Sunday school class is a good format for studying a single book of the Bible for ten months. A podcast would also lend itself to that kind of teaching.

Have you ever considered producing The Liz Curtis Higgs Podcast?

Thomas: Have you ever considered producing The Liz Curtis Higgs Podcast? You could do a season on the book of Esther and spend a whole episode on the word “Paul.”

Liz: The closest thing I’ve done to a podcast is to lead my studies at church and on Facebook Live. Facebook Live isn’t a podcast, but people can listen to it as if it were only audio.

Thomas: We can peel that audio away for you and make it a real podcast if you want.

Liz: This would be a good time to let your listeners know that I have made a big transition from being a full-time speaker and writer to being in full-time ministry at my church in Louisville, Kentucky, where I live.

God has such a sense of humor that he would take me from a national and international ministry to a local ministry. It feels very backward, but I love ministering in the local church. I get a real giggle when somebody comes up to me after Sunday school and says, “Has anybody ever told you you’re a really good speaker?”

I say, “Wow, thanks so much.”

I love not being on a platform. I’m just going to say that. I love not being on a national platform and just worrying about ministry in my church. I want to concern myself with people in my church and not have to worry about how many likes I have on Facebook.

Thomas: That’s what happened with Jimmy Carter. From all accounts, he was much happier as a Sunday school teacher than he was as a president of the United States. He spent decades teaching Sunday school after he retired. He’d be teaching Sunday school at his local church with the secret service watching.

When you transitioned to being a writer who starts from scratch, what did your process look like?

Liz: I sold the idea of Bad Girls of the Bible to Waterbrook Press over the phone. I asked, “Would you be willing to publish a book called Bad Girls of the Bible?” There was a long silence on the other end, and then they said, “Send us a chapter.”

At that point, I had picked 20 women I wanted to write about, 10 of which ended up in the first book.

Potiphar’s wife was the first one I wrote, so I put up the scripture on my screen and quickly realized I was not going to teach a verse at a time. I was going to teach it phrase by phrase.

When I write from scratch, I put all the different translations into my document so that I notice the nuances, then I stop and pray over it. After that, I go back and insert my own thoughts, but I make the font red, so I know which thoughts were mine and which were quotes or ideas from other books.

Then I look at commentaries and add all the reference material to my document.

After I had 40 pages of notes plus my own thoughts, I began telling the story.

In Bad Girls of the Bible, I opened each chapter with a contemporary fictional story based on the ancient biblical story. So, Potiphar’s wife became Mitzi. I set her story in Indianapolis, which was a town I knew well. But I began my writing process with the nonfiction piece, and when I felt good about that part, I’d back up and write the fiction based on the nonfiction.

Each chapter was about 7,000 words. The first 2,500 words were the fictional opening story, and then the other 5,000 was the nonfiction.

Thomas: You’ve outlined a great technique. You created a structure or a template for a chapter, and then you copied and pasted that template across all your chapters. You didn’t have to decide how to open chapter five. You already knew you’d open with a fictional story. You still had to write the story, but you weren’t restructuring every chapter.

That makes the book more approachable for readers, but it’s also easier for you as the writer. Once you’ve got a good chapter template, your outlining is half done, and you just have to fill in the blanks.

Liz: I’ve had a format, hopefully of my own creation, for every chapter and book I’ve written ever since.

After the fiction and nonfiction pieces of each chapter, I’d include a section called “Questions Worth Considering.” I’d include four points and ten questions.

When we repackaged Bad Girls in 2013 for the 15-year anniversary, we pushed the questions to the back of the book because readers had a better reading experience if they didn’t have to leap past questions to get to the next chapter.

Then I’d start the next stand-alone chapter about the next bad girl.

Although the book has an overarching theme and some connectivity, my intent was that people could use it as a Bible study because each week stands alone. In a 10-week Bible study, people are going to miss a week here and there. They’re not going to be there for all of them because things come up. But for this study, they didn’t need to be there every week because each week was about a different woman. I didn’t realize when I created that how well it would work.

Some things we stumble into and find out they work. Bad Girls worked because people could use it as a Bible study.

When I promoted the book, we created a Bad Girls tour, and I spoke in 30 cities within about four months.

I had to come back to churches who’d booked me and ask if I could speak on Bad Girls of the Bible even though they’d booked me for another topic.

One of the first churches said, “But what would we use as the centerpieces?” They were really concerned about that, but others figured out exactly what to use. Churches had so much fun with that book. They still do. The book’s been out for 24 years, and it’s still my biggest seller. It has sold a million copies. People will call me and say, “We’re doing your book,” and I don’t have to ask them which one.

I don’t know how many of those kinds of hits you get in a career. However, I am so grateful it wasn’t my first book. I would have had that bestseller hanging over my head forever. People would have asked me, “When are you going to write another Bad Girls?”

Thomas: It’s psychologically damaging to become famous overnight or be thrust into the spotlight. I experienced it a little when I wrote my viral blog post. Suddenly I was the talk of the town in the middle of a little firestorm of lovers and haters.

Internet firestorms blaze hot, but they don’t blaze long. If I hadn’t already had some training in public speaking and media, the internet firestorm would have been far more traumatic than it was.

Often the praise is more difficult to handle than the criticism because you start to measure your success by the amount of praise you get month to month. When the praise wanes, you may wonder if your value is decreasing. You begin to want and need validation from your fans. It’s an emotionally complicated challenge to navigate.

And it’s difficult as a Christian because God is a jealous God. He will humble you if you start stealing His glory. King Uzziah was a good king in Judah, but his pride led to his destruction. He attempted to burn incense in the Temple, an act of worship that was restricted to priests. When the priests attempted to send him from the Temple, King Uzziah got angry and immediately became leprous.

As a beginning author, you may resent your obscurity right now. You’re working hard, writing base-hit books, wondering when you’ll get your home run. Remember that it may be the mercy of almighty God that you haven’t had your home run. Perhaps your soul isn’t ready for it, and maybe it never will be.

Fame can be tough on you and your family. It’s complicated.

Don’t resent God for not giving you the fame you think you deserve. He loves you more than you think, and he loves you enough to keep you safe from something he knows that you can’t handle.

Of all the books you’ve written, which was your favorite?

Liz: I’ve never seen myself as famous, but I have been grateful for the things God has and hasn’t done.

My favorite book I ever wrote is not one of my big sellers. I’m not sure it even earned out the advance. It was called Embrace Grace: Welcome to the Forgiven Life. It’s my favorite subtitle.

I’ve begged my publisher to keep printing it when I’m gone because I’ve gotten so many letters about how it has ministered to people. Even if it was a small book in sales and size, it was a total book of my heart. I wrote that book in two weeks, which wasn’t typical for me.

When people come up to me and say, “This book so spoke to my heart,” I can look that person in the eye and say, “I wrote it for you.”

I’ve written 37 books. Some were home runs, others were base hits, and some were fly balls. But it’s ok. God will bring about his will for your books. We do our part of the writing and marketing, and God does what he wills with the various printings.

Publishers always say the first printing is a marketing printing. The second printing tells you that the book has legs, and the 20th printing tells you it has a long tail.

Thomas: The second printing is where the profit tends to be.

Many book production costs are fixed and not connected to the number of copies printed. Cover design, editing, and writing are all fixed costs. As you sell more books, those fixed costs decrease per copy.

For example, if editing costs $5,000 and you sell one copy, then that copy costs you $5,000 to edit. But if you sell 5,000 copies, the edit only costs you $1 per copy.

Suddenly publishing a book becomes inexpensive. The economics of publishing shift around as you sell more copies.

Liz: And let’s remember that Christian publishers have to make money so they can keep publishing books. They’re allowed to be a business. And because of that, they might have to say, “As much as we’d love to publish your book, we can’t because we’re going to lose money on it.”

Thomas: Can you imagine any other kind of business being required to justify their expenses? Imagine a Christian plumber apologizing for charging you and trying to justify his costs because he has to feed his family.

That’s ridiculous. He’s offering a valuable service and has earned his payment.

What was the biggest challenge you faced in your career?

Thomas: Walks us through some of your valleys of the shadow of death in your career.

Liz: I’ve been so grateful for the support of people who believed in what I was doing. I’m so grateful God has prevented me from doing stupid things on several occasions. Although there were a few occasions he just went right ahead and let me do stupid things.

Another book that did not come close to earning back its advance was an “armchair travel” book. The head of the publishing company said to me, “I love armchair travel books. Couldn’t you do a book of armchair travel based on all those trips you made to Scotland to research your novels?”

I figured I did have tons of notes from my trips to Scotland, and I was sure I could write them.

But have you ever looked for the armchair travel section in a Christian bookstore? There isn’t one.

But by that point, I had written four novels, and I knew I could write it. But when that book came out, I had lots of novel readers who bought it and said, “What was that?” It wasn’t like any of my others.

When I did book signings, we couldn’t help people sort out what it was. It was a fiasco.

I shouldn’t have listened to my publisher, and I know that sounds counterintuitive. But by that point, I had a lot of books out, and I should have said, “I am so glad you love books like that. I’ve never written a book like that. Christian bookstores don’t have a shelf for that. This will not do well.” But I didn’t have the courage to say that, and I let my ego tell me that I could write anything. In truth, I could not write a bestselling armchair travel book.

Even in a secular bookstore, armchair travel doesn’t sell that well. So, I learned a hard one there.

Thomas: The lesson here is that you, as the author, are responsible for protecting your own brand. No one understands your brand like you do.

A brand is a promise. You’re making a promise that a book by Liz Curtis Higgs will be like her other books. Expectations are based on past experiences.

Bad Girls of the Bible was a perfect segue book. Opening a nonfiction chapter with a fiction anecdote allowed you to demonstrate your fiction and give people a taste without having to buy in. You let them sample your fiction before you wrote a novel.

Beginning authors often want to write all kinds of books, but focusing on one genre is almost always the path to commercial success.

Liz: Yep. Do less and do it better.

What mistakes did you make in your writing career?

Liz: When I look back at 30 years of writing, I’ve learned a lot from my mistakes.

There was one occasion that wasn’t necessarily a mistake, but it was definitely a learning experience for me and a marketing nightmare for my publisher.

I’d pitch my publisher new and fresh ideas all the time. I’m a saleswoman, and I’d convince them that if I could sell my idea to them, I could probably sell it to my audiences. So, I wrote humorous, nonfiction books based on my messages. Then I wrote four children’s books, which were not funny but also sold a million copies.

Since they did well, my publisher wanted more. I said, “Those were the four that God gave me, and I wouldn’t dare try and write without him.” But they talked me into it, and I wrote a children’s book that sold maybe 40,000 copies over several years. Relative to 1,000,000, those 40,000 were not considered a success.

Even the copies it did sell were coasting off the success of the previous four books. That book had the same author and artist, but it was a Liz book, not a Lord book. I came up with the idea in my head instead of searching my heart and seeking God. It was an ego book.

All my failure books were ego books I thought I could make work. I thought I knew enough about publishing and marketing, and now I just know better.

My books needed to be God’s idea from God’s seed growing in me. It had to be a book that was beating so loudly in my heart that I couldn’t not write it. That is a high-passion stage.

Publishers love an author with passion for a subject and an audience. Mine was Jesus and grace.

Thomas: I love that because it ties in with the first commandment of book marketing, which is “Love thy reader as much as you love thy book.”

You must love your reader and your book, but beginning authors often only want to write what’s on their hearts whether readers like it or not.

Liz: There’s just no fruit in that. Writing a book for your own pleasure without thinking about your reader is fruitless. A book that’s written and not read is not a book.

Thomas: It’s dead trees and ink. A book only comes alive in the mind of the reader. Dead trees and ink will soon be composted or recycled. But if it’s in someone’s mind, it’s alive.

Just as the molecules in our body come from the molecules we eat, our mental space is made of what we consume by listening or reading. As a Christian author, you get to provide spiritual molecules for your reader’s mind, and that responsibility should be handled with fear and trembling.

Liz: Writing is so hard. Speaking is easy. You do it all day long.

Writing is hard. It’s a solo bit. Of course, the Holy Spirit is with you, but you don’t have feedback from an audience. When I write something, I sometimes wonder whether it makes sense or if it’s powerful. Writers do a lot of second-guessing, and that’s why you need great editors. You need someone to say, “Was this supposed to be funny? Because if it is, you need to explain the joke to me.”

What did you write after the nonfiction, the Bad Girls series, and the children’s books?

Thomas: After the Bad Girls series was a hit, what did you write next?

Liz: Writing the fiction pieces for Bad Girls really opened my heart to fiction, and I already wanted to write fiction. In fact, the reason I did Bad Girls was because the publisher wanted me to write a nonfiction book before they’d publish my fiction.

When I started writing Scottish historical fiction, it was a huge shift. It had nothing to do with any of my previous books or work experience.

I had many pages of ideas and notes, but it wasn’t clicking with me or the publisher. They said, “We see something here, Liz, but what is the story you want to tell?”

God, in his kindness, gave me an ah-ha moment when I was standing in a shower. It hit me. “Oh, my goodness. I want to tell the story of Leah and Rachel and Jacob set in 18th century Scotland because Jacob was a shepherd.” It took off from there.

I pasted the text of the Bible story from Genesis into a document and literally did a find-and-replace. I changed Leah’s name to Leanna and Rachel’s name to Rose. I called Jacob Jamie, and when it rolled out in front of me, I could see it was such a great story. The rest came quickly, and the publisher caught the vision right away.

Thomas: You were still writing about women of the Bible, but you set them in 18th-century Scotland. It worked with your brand because the book was for the same kind of reader.

Christian authors have more freedom to go between fiction and nonfiction because there’s a commonality in the target readership and theme.

Even C.S. Lewis sprinkled themes from his nonfiction, such as this Lord, Liar, Lunatic argument, into his fiction Chronicles of Narnia. When Lucy visits Narnia, she comes back, and the professor helps the children figure out whether Lucy’s a liar, a lunatic, or telling the truth about Narnia.

Nonfiction and fiction allow you to present the same truth from different perspectives. Few people have ears to hear the Jesus message, but they do have ears to hear the Lucy message, and maybe that softens their hearts for hearing the Jesus message later.

Secular authors have a hard time shifting between fiction and nonfiction because it doesn’t have that connection or shared audience.

As a Christian author, you have more freedom around your genre as long as you have the same target reader.

Liz: When I first approached a publisher about doing fiction, they asked me, “Who’s going to write it?”

I said, “Oh, I thought I would.”

They said, “No, no. You’re a nonfiction writer.”

The expectation was that I couldn’t possibly do both, but I have, and I love both. They’re very different processes. The only thing fiction and nonfiction have in common is punctuation, and you don’t even use punctuation the same way. They require entirely different research and skills.

Thomas: Just because you’re a successful nonfiction author doesn’t mean you have the skills to be a successful fiction author. You must work to learn the craft and “get good,” as we would say in the video game world.

You don’t get nearly as much transfer credit between the two genres as you would think. Fiction writing is very different from nonfiction. Do you know how to hold tension? Do you know how to embrace mystery? Do you know how to play with the knowledge that’s in the reader’s head?

Nonfiction is all about putting as much knowledge into your reader’s head as quickly as possible, whereas fiction is about withholding information to make them curious.

Liz: When I got into the fiction world, I started attending fiction writers conferences and reading fiction by the ton. I had to get serious about the craft of fiction and go back to square one as a writer.

I’m just grateful my readers were willing to try my novels. I had to just go to my readers and say, “God put three words in my heart: Scottish historical fiction.” The first time I heard those words was in 1995, and my first Scottish historical novel came out in 2003. I spent eight years studying fiction, studying craft, reading good fiction, traveling to Scotland, and amassing books about Scotland.

I’m embarrassed to say it, but I have 1,050 books on Scotland. They are all over my house and garage. I just didn’t want to write a half-baked story. If I was going to be a Scottish historical writer, I wanted to know Scotland, its history, and something about fiction writing.

What advice or encouragement do you have for authors at the beginning of their careers?

Thomas: As you reflect on a long career, most people reading or hearing this are just beginning. What advice or encouragement would you have for them?

Liz: If you call yourself a Christian writer, then your Christian faith, your love for Christ, his word, and his people, must be number one. It can’t be the platform or your skill set. You must love Jesus with your whole heart and trust him to open the doors for you.

Every good thing that has happened to me in my writing and speaking career is because of God’s kindness, mercy, and love. It has nothing to do with Liz. To me, it really is all about Jesus.

Long ago, Thomas, you and I discussed marketing. You had fabulous tips that people need for building a platform and marketing. You asked me, “What’s your marketing plan?” I said, “Well, I write the books God tells me to, and I trust him to put them in the hands of readers.”

And you said, “How’s that working out for you?”

And I said, “Honestly, pretty well.”

But I never had it as my goal to be the number-one anything. I just wanted to successfully put God’s heart for the reader on the page and to love my readers. Over the years, loving my readers has meant writing them back and looking them in the eyes when they’re talking to me after I’ve spoken. They matter as much to me as anybody.

You can’t manufacture genuine care. And if it’s not happening genuinely and naturally, go see Jesus about it. He alone can make you what you long to be, which is a person who communicates on the stage or the page. It has got to be, all the way to the bone, the message God wants people to hear and has chosen you to communicate.

Connect with Liz at her website or check out her homerun book, Bad Girls of the Bible.

Featured Patron

Kelly Jo Wilson, author of Tearing the Veil

In life, you face rejection, hopelessness, and feeling disconnected from God. But you don’t need to handle it alone. Learn how Jesus made sure you never have to be separated from God and how much your life is truly worth.

The Christian publishing show is now also on Substack. If you want to support the show but don’t want to use Patreon, find the Christian Publishing Show on Substack.

Sometimes it makes me wonder,

when I listen to the pros;

was this writing gig a blunder?

And maybe everybody knows

that there was no talent-reservoir,

no real inspiration.

I should, perhaps, have shut the door,

and gone on a vacation.

But it’s too late now in life and night,

oh-dark-thirty, wrapped in pain,

and I guess I really might

as well go ’round the track again,

run the race against just me,

one more attempt at sonnetry.

Absolutely great!

Great post. I learned two things,

1. Why Liz Higgs is a great and successful writer

2. That human writers have nothing at all to fear from AI.