Some people would have us believe that boys and girls are the same. They assert that the differences between genders are merely social constructs imposed upon us. Even physical differences are considered “flexible.”

The Bible teaches that God created us male and female. Common sense tells us that boys and girls are different. Science tells us that males and females differ, right down to the number of chromosomes in every cell.

So what does this mildly controversial statement of the basic facts of life have to do with writing a book? A lot, actually.

To write a book readers want to read, you need to know what kind of book they want to read. Don’t assume all readers are the same because they are not.

You can improve your book without excluding readers outside your target audience by focusing on a certain kind of reader.

One of the hardest audiences to write for is young boys between the ages of 8 and 14. If you can thrill them, you can thrill anyone. If you don’t believe me, just ask J.K. Rowling.

By writing her books to thrill 12-year-old boys, she was able to write books for boys that thrilled millions of people of all ages.

If you are writing for young boys, you’ve likely heard Christian publishers and agents say they don’t know how to sell books to that demographic.

But don’t let that statement convince you that boys don’t like to read. Boys will read if they have a book they love. S.D. Smith’s books thrill 12-year-old boys, and he has sold over a million copies.

It can be done. Don’t listen to anyone who says it’s impossible.

When I was a 12-year-old, I bought and read dozens of books every year.

How do you write books boys will love?

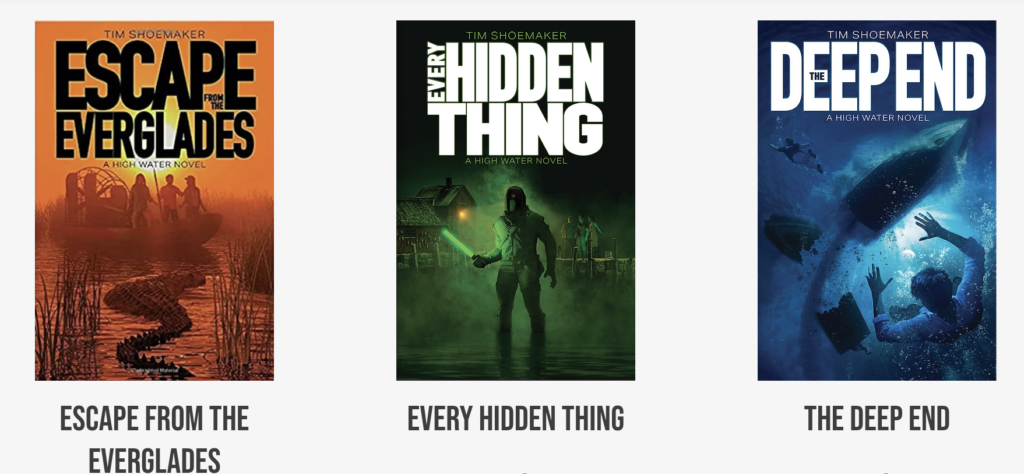

I asked Tim Shoemaker, who is an expert on writing books for boys.

He is an award-winning author of twenty books and is a popular speaker at conferences and schools around the country. Over twenty-five years of working with youth has helped him relate to his reading and listening audience in a unique way.

Thomas Umstattd, Jr.: Why do many Christian writers find it challenging to write for young boys?

Tim Shoemaker: Writers tend to lump boys in with “kids” in general. They write to a group, which is a nonentity. Boys and girls are different; and if we don’t consider that, we’ll miss that whole market segment.

Thomas: Shooting between two targets is not the same as shooting at both targets.

You have to first shoot at one and then the other. Any duck hunter knows you can shoot multiple ducks, but you have to shoot each one individually.

If you want to reach boys, you must specifically focus on boys.

How would you aim your writing directly at boys as your target readers?

Thomas: If you’re starting a new project targeting 12-year-old boys, how would you craft that book to thrill them?

Tim: First, remind yourself of the differences. If we only think of “kids,” we’ll get ourselves in trouble.

For example, consider the difference between how boys and girls communicate. Boys will address love, fear, anger, and friendship differently than girls do.

How do you accurately portray a boy’s emotions?

Aggression

Aggression is a broad wavelength for boys. They like to communicate through aggression, whereas girls might use their words.

Anger

A boy might punch somebody.

Fear

They won’t walk cautiously through a dark alley. They’ll run full speed, screaming their heads off to make a potential attacker think they’re crazy or perhaps simply to startle a would-be assailant. It’s not a great strategy, but boys have a different way of approaching things.

Friendship

They don’t want to talk to their friend on the phone. A boy might wrestle their friend, slug him in the arm, or trash-talk him in a game; but all those approaches to friendship are different from a girl’s.

Love

Boys won’t say they love somebody, but they may give a hug.

That targeting principle is also true with marketing.

Boys are hammers. Hammers break things, but they also fix things. Girls are more sophisticated. Girls are like smartphones, and boys are like pencils. That doesn’t mean boys aren’t smart, but they’re a little simpler. They’re used to smaller and fewer words. When we remind ourselves of these differences, they will be reflected in our writing.

Why do you need to portray the differences between the genders?

Thomas: You’re saying that one element is to accurately portray boys. If a boy is reading a character who isn’t believable, it will affect the boy’s interpretation of that character.

If your worldview says that boys and girls are the same and all your characters are generic copies of each other, the young men reading your book won’t feel like they’re expressed on the page. At the same time, the young women reading the female characters won’t feel like they’re expressed on the page either.

Say what you want about J.K. Rowling and her politics, but she strongly believes in the differences between the sexes. She portrays that on the page in a way that resonates with young people. Readers can relate to specific characters in her book because they’re based on observations of real people who are distinguished from each other.

Tim: I picked up this book called Up to No Good by Kitty Harmon, which describes boys. She quoted a 13-year-old who had written a memory:

When we were 13 or so, my friends and I had this game.

We’d go down to the basement, where it was completely dark, and each of us would find a hiding place. Then someone would start the game by turning out the lights, and we’d try to hit each other with darts. You’d think you’d hear someone make a noise, and you’d come out of your hiding place throwing darts but cringing because you were fair game too. There’d be complete silence. Then you’d hear somebody yell, “Ow!”

One time we turned on the light, and the guy had a dart dangling from his cheek just below his eye. After that, we wore goggles.

Up to No Good by Kitty Harmon

I love that story because it demonstrates the difference. No one said, “Hey, this is stupid. We should stop.” They’re asking, “What do we need to do to keep doing this? Let’s wear goggles, and go back to playing this game.”

How do you write dialogue in a book aimed at boys?

If the story you’re writing has a boy sitting at a table talking with somebody for a while, it won’t feel right. The boy won’t identify with the character because it doesn’t feel like him.

Everything you do to ratchet up the tension or conflict will fall flat because the boy doesn’t relate to the character.

The boy may also wonder if there’s something weird about himself since he never sits at a table talking for long periods of time. If you show somebody in a conversation standing there, rather than doing something boys like to do, it won’t feel right.

But if you put that character in a car, he could look out the window. He doesn’t have to look at his mom when they’re talking. That’s a more realistic conversation. You’ll want to include his interior thoughts too. What is he thinking, and what is he saying?

If that conversation occurs at night when he’s in bed and it’s dark, then when Mom or Dad comes in to talk to him, they can have a better conversation. The face-to-face stuff for any length of time doesn’t feel real.

Thomas: Beware of the long pages of dialogue. A book targeted at girls might include an intense discussion, but boys need dialogue interspersed with action.

What purpose does the action serve in a book for boys?

Tim: Keep your characters active and not just sitting in chairs, talking to each other. If you want to write a conversation between two people, make sure there’s some sort of activity going on. That boy needs to be moving.

Thomas: Realize that action isn’t a break in the conversation. When a boy reads a book, the action is an extension of the conversation. If the characters start punching, that is also communication.

Some films don’t get this right. They force a meaningless action scene just because they know the movie requires one. The scene doesn’t resonate with viewers, and the movie doesn’t do well.

When the action scene is an extension of a conversation, it works better. A perfect example of this is in Captain America: Civil War, where Captain America and Ironman are fighting. Their fight isn’t about who’s stronger. The action is an extension of the argument they’ve had throughout the movie, but they’re arguing with their deeds as well as their words.

How do you design a book cover for boys?

Tim: A boy will look at the book’s cover first; and if it doesn’t grab him, he won’t get past it.

If you’re writing and self-publishing a book for boys, you must carefully consider the cover design. If it looks too juvenile, the book is dead to him.

Thomas: Marketers sell products to young men by targeting them with advertising that features slightly older young men. If you want to sell a Nerf gun to an 8-year-old boy, put 12-year-old boys in your ads. The younger boys think, “Ooh, the big kids are playing with this Nerf gun! I want to do what the big kids are doing.”

No 12-year-old boy wants to buy a product advertised by 8-year-olds. A juvenile cover is a huge red flag to boys.

In fact, I was drawn to G.A. Henty when I was young. Henty was a Victorian author popular with young men. In the 90s, the book was presented to us as a book for adults that we were allowed to read. It covered adult concepts through historical fiction, and it was violent.

In the Victorian era, they were YA books; but they felt like books for grown men. It was a book my dad could read and not be embarrassed by.

Tim: Boys want to appear older than they are. If you want to target a 12-year-old, you’ll probably want your protagonist to be 14 because your readers will want to be like that person.

Everything starts with the cover. It can’t look girly or feminine. Pay attention to the typeface and style.

How do you design the interior of a book for boys?

Tim: Give them plenty of white space. If they get past the cover and open it up, they’ll want to see if the page looks friendly. You have to break up the text with interior thoughts and dialogue.

What kind of opening paragraphs do you need to hook boys?

Tim: You only have a few seconds to grab them. They’ll read that first line and then the first paragraph. If you don’t grab them with the opening, it’s completely over.

Your strong opening needs to do several or all of the following:

- Draw the boy in

- Create a question in his mind

- Ask a question

- Intrigue him

- Hint at danger or trouble

- Invoke mystery

Avoid these mistakes in your opening:

- Don’t set anything up.

- Don’t worry about showing the setting.

- Don’t give background with some kind of zoom-in start.

You have to jump right into it. I think that’s one of the most fun things about writing for boys. Why wouldn’t a strong opener work for girls as well?

How has writing books for boys changed over the years?

Thomas: How have you seen writing for boys change over the years? The boys you wrote to 15 years ago now have boys of their own. What has changed during your time in the industry?

Tim: There’s a polarization of some of the writing. The good writing is getting better, and the writing that wasn’t as good is dropping off. We’ve talked in a previous episode about showing instead of telling.

Books written 15 years ago had less showing and less deep point of view. They had fewer solid interior thoughts. While those books were good, they could have been better. Today the writing must be better, or boys will not pick up the book.

In the old Hardy Boys books, readers never got inside the characters’ heads. The stories have so much telling instead of showing that they lack the power they could have had.

Thomas: I had a hard time connecting with the Hardy Boys. My mom pushed me to read those books, but the Hardy Boys didn’t resonate with me.

However, Ender’s Game did resonate with me. It’s a great example of a book with strong interior dialogue. The book was hard to adapt for film because the whole story takes place in Ender’s head. His conflicts are internal.

Boys are less expressive than girls, but that doesn’t mean they think fewer thoughts. They’re just thinking those thoughts to themselves, which is where fiction writing has an advantage over film.

It’s hard to get inside someone’s head on film, but it’s easier in a book. You can show that interior dialogue in a strong way.

Ender’s Game has done very well. It has stood the test of time, and it’s a book that gets inside the head of a 12-year-old boy.

Tim: I remember reading that book, and you’re exactly right. Very few words are spoken by the character, but he is thinking. That’s what’s so delicious for the reader. The reader identifies with the character because his thoughts and actions feel like something the reader would think or do.

What point of view works best when you’re writing books for boys?

Thomas: Good stories combine action with dialogue and interior thoughts. The interior thoughts give readers an entirely different perspective. In Dune, you get interior thoughts from all the characters. The author head-hops around, which is a big no-no in Christian publishing. Christian editors like the third-person, limited point of view.

But Dune is a magical book because you get to see when a character is being duplicitous. You get to observe a character’s integrity (or lack thereof) because you know the motivation behind their words. It’s fascinating. The best scene in the book had to be left out of the movie because all the tension happens inside the characters’ heads.

I’m not saying you have to use the omniscient point of view, but it does allow you to show duplicity and the thoughts that motivate action.

Don’t be afraid to get into the characters’ heads, but remember that it requires a higher level of writing. Head hopping must be done carefully. It forces you to write three-dimensional and fully fleshed-out characters.

Tim: I don’t use the omniscient point of view, but I tell the story from four or five points of view. Characters get their own chapters.

When I’m writing, I list all my chapters and record whose point of view is represented in that chapter. If I’m targeting boys, I write about 70% of my chapters from the male point of view and the rest from a female point of view.

Boys can only handle a limited amount of the girls’ chapters, but the girls love reading about the boys, so it works.

Thomas: If you write the deep point of view well, boys will want to read what’s happening inside the girl’s head. The superficial point of view isn’t intriguing, but boys are intrigued if you show what’s motivating the female thinking. That was the appeal for boys who read Twilight. They wanted to know what those teenage girls were thinking.

Tim: I agree. They want to know to a certain extent, but they can only take it in smaller doses. You can write the deep point of view, but don’t make that a long chapter because boys can only handle so much at a time.

Why are anime and manga so popular with kids right now?

Thomas: Anime is popular with young people right now. The best-selling type of comic book is manga, the comic-book version of anime. It outsold all American comic books combined in the United States. American young people are choosing manga and anime over American comic books.

One of the big differences between Eastern Japanese storytelling and Western storytelling is that anime and manga acknowledge the differences between men and women. The boys and girls in the comics are very different. The women are very feminine, and the men are very masculine. There’s variety in anime, but a lot of manga features that strong difference.

I heard one young man complaining that American writers don’t know how to write good female characters. He said, “They’re just the male characters, but female, and I find that very boring.”

Kids are gravitating to Japanese storytelling. Interestingly, when Americans adapt those incredibly popular anime stories for Netflix, they use Western storytelling; and the whole thing falls apart. American writers ignore the differences between men and women, which is what made it interesting and popular in the first place.

Hollywood is doing the same thing. They’ll take a popular male character and just swap out the gender and make the character a female. They change nothing else about the character because their worldview tells them that males and females are exactly the same.

But those swapped-out characters don’t resonate with audiences. They don’t resonate with males or females, and Hollywood wonders why they’re having trouble selling theatre tickets.

If I look at the situation as a businessperson, I can see Hollywood is dropping the ball; and this is the moment for authors to shine.

Movies used to be the biggest challenge for writers because kids preferred movies over books. Now kids are desperate for something that resonates with real life.

Hollywood has gotten so far from real life that it’s failing to resonate with a lot of young people.

Tim: That is a good observation. I love showing those misunderstandings between boys and girls in my books. They go back and forth, and it adds so much tension. It’s much more fun to write.

Thomas: It’s useful too. As a young man, I wanted to understand young women. A book that portrays women and men well is appealing because it helps us understand one another.

Tim: When you can get into the characters’ heads and show their interior thoughts, it’s so revealing. A reader can see that a character thought one thing but said something different. Of course, if the character had just said exactly what he was thinking, they might have avoided the tension; but that’s not as true to life.

Thomas: As the author, you can portray a scene from the male character’s point of view in one chapter and the female point of view in the next. Since you have the objective view, the reader gets three different perspectives on the scene.

That approach tells readers a lot about each character and how they interpret the same events. It makes the characters and the book more interesting.

What are your “must-haves” if you want your book to resonate with boys?

Tim: I keep the chapters short and always end with a cliffhanger. If they can turn the pages fast, they’ll enjoy the book more and have a sense of accomplishment.

Why do I need to write short chapters in a book for boys?

Thomas: It’s not about attention span. People complain that boys have short attention spans, but that’s a myth. A 12-year-old plays Minecraft for four hours without taking a bathroom break. That’s a long attention span.

Instead of questioning a boy’s attention span, we should be asking what will hold his attention for four hours.

If authors simply complain that boys don’t have the attention span, it takes the pressure off the author to write a great book. It becomes the boy’s fault that he doesn’t like your writing, and suddenly you’re absolved of all responsibility.

Authors must take responsibility for their writing and learn to hold their readers’ attention.

Thomas Umstattd, Jr.

You write short chapters because it gives the boy a sense of accomplishment, not because he has a short attention span. Boys feel like they’re winning at reading if they can accomplish a chapter.

Tim: If their mom says, “You’ve got 15 minutes to read before lights out. You should be able to finish a chapter in that time,” If he can’t finish a chapter, he feels frustrated.

As the author, I want to finish the chapter on a cliffhanger, so the boy wants to return to it the next day. I don’t want them to forget where the character was and then have to reread. That’s annoying to boys.

How much description and detail do boys want?

Tim: We writers love to describe something or set a scene with so much description, but we must avoid that when writing books for boys. For the most part, boys don’t care what somebody’s wearing unless it’s a soldier.

Boys rarely care about clothing or food descriptions. Don’t describe the kitchen. They don’t care, and it annoys them.

Describe the Right Details

If a character drives up in a pickup truck, you better say what kind it was. Was it an F-150? What was it?

Thomas: Typically, women are more oriented around people, and men are more oriented around things. If you want a book to resonate with a young man, you must describe the physical things your character touches. Boys don’t care what the character is wearing; but if that character is holding a gun, you better describe it in detail.

Was the sword covered in blood? How was the scabbard attached? How has that person used the weapon in the past? I’m curious about those details, but I don’t care about his uniform or mustache.

Tim: Choose to describe the right things. Please don’t write a character who pulls out a “handgun.” That’s ridiculous. Boys want to know the caliber, brand, and model.

In the Hardy Boys books, a character would drive up in a “sedan” or “coop.” I mean, come on! Boys want the details.

Authors should aim to describe the right things and not belabor the details that boys find uninteresting.

Thomas: Work interesting objects into your story that are worth describing.

Talk about the tricorders, lightsabers, and blasters. Pretend your story will become a movie, and you’ll need to sell some toys and merch. What will you sell? Work the merch into your story.

Maybe you’ll never sell the merch, but it’s worth considering because millions of people have bought Harry Potter’s wizard staff.

If you’re a woman writing books for boys, you’ll need to consciously work some of those physical items into your story.

How do you make your story believable for boys?

Tim: A character who takes actions that your reader can’t believe is the kiss of death. It will pull them out of the story experience and remind them they’re reading.

Thomas: Believability doesn’t mean you can use spaceships and magic. It means that you set up the rules of your story, and then you have to follow the rules.

If you say the forest in your story is split into light and dark sides, but you add a character who’s neither dark nor light but still uses the force, you’re breaking the rules of your own story. That’s what makes it not believable.

How do you write a main character a boy will love?

Tim: You must write a character the boy identifies with.

Your character needs to be someone who

- the boy would like

- has a clear goal

- the reader will care about right away

If you don’t have those elements, nothing you do to ratchet up the tension will work.

How do you write a satisfying ending in a book for boys?

Tim: A satisfying ending allows the boy to feel good about reading and finishing the book.

If it’s a mystery, they want justice. They want the killer to get caught or to get what’s coming to them.

They want the hero to win. Boys want to see the character face their deepest fears or weaknesses and become stronger and better. Create a character who takes what little they have and conquers their fear of the enemy.

How do you write characters a boy will like?

Thomas: We’ve been talking about the difference between boys and girls, but this is one area where there’s a difference between boys and men.

Avoid Writing Complex Characters

Boys aren’t ready for a complex antihero. They don’t want a lot of nuance, texture, and complexity. As readers age, their reading preferences mature; and they like more complex and nuanced characters.

As a young reader, I wanted a hero who suffered and overcame suffering but was still a good person. I rooted for Luke Skywalker, who was always a good person despite suffering through trials and failure.

The new Luke Skywalker is a coward, and I wouldn’t like him or root for him. I wouldn’t care that he was a powerful antihero because he wouldn’t resonate with me. Honestly, I don’t like the modern Luke Skywalker.

A boy’s ability to think abstractly grows over time. He sees the world as very cut and dried. There are good guys and bad guys.

As an author, you might get frustrated with that 12-year-old boy because you want him to know there’s no such thing as a good guy because we all struggle with sin, and I want to show you the sins of your hero.

A 12-year-old doesn’t want that. He wants a good guy he can root for.

Avoid Giving Your Characters Too Much Help

Tim: Great characters always have to make choices. Your hero should have the option of taking the coward’s way out and doing the wrong thing. Make the stakes and consequences high, but let your character make the hard, right choices. Boys can love a character like that.

Boys don’t want their problems solved by others. They want to solve the problems themselves. Your characters might get help or input, but they don’t want people doing things for them.

Avoid Stereotypes of Boys

Not all boys like sports. Not all boys communicate as well as we wish they would.

If a writer thinks boys are stupid because they do dumb things, that belief will come out in their writing. Even if the author wouldn’t articulate that belief out loud, their writing will give off a parental tone. Boys will know there was something they didn’t like about the story, even if they can’t pinpoint the problem.

Thomas: It’s inaccurate to say that boys are stupider than girls. Boys simply weigh risk differently.

Similarly, alcohol doesn’t make you stupid. It just causes you to weigh risks differently. Drunk people know they’re doing stupid things, but they don’t feel the risk like a sober person does.

For example, a drunk person knows that drinking and driving is risky. They give intellectual ascent to it but don’t feel the risk.

Young boys know that throwing darts in a dark room is dangerous, but that danger is part of the fun; and they judge it differently.

If you write as though you’re an outsider saying, “You’re an idiot for doing that,” your voice is unattractive to that young man. He won’t want to read a book written in that voice.

Tim: Your true beliefs will bleed through your writing. Before you write your book, you must realize that boys are smart. They lack experience, can be impulsive, and will make bad choices; but they’re not dumb.

Through our stories, we can present our characters with choices; and our readers can gain from the experience of our characters. We can help protect our readers from traps and dangers by putting those things in our books and seeing how our characters grapple with them.

Avoid “Telling” About Danger

Thomas: We must show boys why something is dangerous. You can’t tell them, “Throwing darts is dangerous.” You just show the kid with a dart in his face, bleeding. They’ll realize it’s not a good idea.

Tim: You’ve got to trust the reader to pick up on that and not try to add a highlighter to the text.

Avoid Preaching

Our writing can’t be preachy. Sometimes we’ll write a character and make him remember part of the pastor’s sermon with points we’re trying to drive home. It’s preachy and ineffective.

Beware of writing to an agenda. Do not write to an agenda. It’s okay to start writing without knowing what deep theme you’ll hit. Let the Lord clarify that as you write.

Sometimes I’ll be halfway through writing a book when I finally realize what point the Lord wants me to make. At that point, I can go back and rewrite to set it up better.

I would rather start writing without an agenda than look like I’m writing to make an agenda work.

Avoid Romance

Tim: Kisses are the kiss of death. Lose the romance. If you’re writing to middle-grade boys, leave it out.

Thomas: I want to illustrate why that’s a mistake. Even if you don’t include kissing, you need to know the difference between eros and phileo love.

In his book The Four Loves, C.S. Lewis discusses the different kinds of love.

He describes eros love as romantic and provides the image of two people looking at each other. Eros love is self-reflective. People demonstrating eros discuss their relationship, write poetry, sing songs, and discuss their feelings.

Phileo love is brotherly love, and Lewis gives the image of two people side-by-side. Two guys who have been friends for 20 years aren’t going to say, “I really like you.” Phileo love isn’t self-reflective. You show love by remaining friends throughout the years.

Young men aren’t ready for eros love.

I realize I’m saying some controversial things, but they weren’t controversial a generation ago.

Tim: The romance often makes that boy uncomfortable because he’s not ready for it. If they’re uncomfortable, they will never recommend your book to anyone. Writing romance in a book for boys isn’t worth the risk of having them dislike your book.

If a boy feels uncomfortable reading your book, he will never recommend it to anyone.

TIM shoemaker

Some authors argue that they need to add a little romance to get the girls into the story, but I would not recommend it. Don’t do it. The girls will find romance by reading between the lines. Even if it’s not there, they’ll find enough to satisfy them.

Avoid Cheap Shots

Tim: Avoid cheap shots like making parents dumb, stupid, or irrelevant. Be careful how you portray authority figures. You can include some bad authority figures, but don’t make all of them bad.

To portray all adults as bad is such lazy writing.

We want our kids to find adults they can trust, confide in, and consult. Don’t put your characters in a situation where they only get advice from their friends.

Thomas: Baby boomers are prone to write that way. The boomers had a lot of conflict with their parents and authority figures. These days, kids are sometimes too submissive to their authorities in that they believe everything their teachers tell them.

The dumb-authority-figure story may have resonated with somebody born in the 1960s, but it won’t resonate with somebody born in the 2000s. Young people aren’t rebellious in that same way. They’re seeking leaders they can feel good about following.

Tim: I sometimes create controlling, manipulative, and abusive characters. I want readers to see what that looks like so they can recognize it and avoid it.

Sometimes, parents say, “I want my son to be a good leader.”

That’s understandable and good, but God has wired us to be followers. I want my kids to know who to follow. In my stories, I want kids to see which character gives the best advice and counsel. We must show them who’s worth following and who they should avoid.

Thomas: You can’t lead others until you can lead yourself.

That’s challenging for boys, especially as they’re entering puberty. They’re being flooded with testosterone, which makes self-control more difficult. Today self-control isn’t a popular virtue, but it’s a key to success in life.

Self-control isn’t a uniquely masculine virtue, but it is a uniquely masculine challenge in that if you’re not getting flooded with testosterone, you’re not being tempted to the same degree. Your impulses aren’t as strong.

The classic conflict “man against himself” would resonate with young men.

A boy often fights to do what he knows is right, even when he doesn’t want to.

Star Wars becomes more interesting when Han Solo comes back and fights, even though he wants to run away with his money.

Avoid Unfamiliar Words and Phrases

Tim: Don’t make your writing too hard to read. I’m not trying to give my readers a vocabulary lesson. I want to tell the story in the most compelling, exciting way possible.

Avoid Flawlessness

I want to make sure I’m not creating characters who have flawless looks or abilities. I want to portray the average kid.

If I show the average boy or girl succeeding or fighting their way through, I’ve given my reader, who likely feels very average, some hope.

Thomas: “Mary Sue” is a fictional stereotype representing a flawless and perfect character. Mary Sue tends to be unlikable, but you can handle that character in a couple of ways.

First, you could make her the villain. Think of Mary Poppins. She’s the antagonist who keeps Mr. Banks from getting what he wants. Mary Sue makes a great villain.

Your second option is to make her suffer. The more perfect she is, the more she needs to suffer if you still want her character to be likable. Think of Wesley in The Princess Bride. He’s perfect. He’s smarter than the smart guy, stronger than the strong guy, and better with a sword than the sword-fighting guy. But he also suffers more than all the other characters combined.

If he didn’t suffer in the pit of despair, we would hate him as a character. But because he suffered so much, we root for him.

If you add a flawless character, you’ll have to torture that poor character to make it work in the story.

Avoid Cliché Attitudes

Tim: Moms can write excellent stories because they’re so observant, but they must be aware of their own opinions and inner beliefs.

For example, if you secretly believe that boys have it easier than girls, that will come out in your writing; and it will not resonate with boys.

In reality, each gender has its own unique set of very difficult hardships. The sooner we understand that, the better.

Thomas: We all have a cognitive bias where we tend to overweight our own challenges and underweight the challenges other people face. We always feel like we’ve got it hard, and others have it easy. Young people have that bias as well.

If you want to write a book that will resonate with boys, you’ll have to overcome that cognitive bias and realize that other people have struggles too.

Tim: We’re talking about targeting boys, but we want girls and boys to love our stories. But it’s important that we get the books boys will want to read.

Boys need to be shown what it means to mature. We need to give them books that show what it means to make the right choices, to persevere in hardship, to be warned about traps, and to grow in their faith.

Our stories can show what it means to become a man by God’s definition. What does a godly man look like? I want my female readers to know what a godly man looks like so they can recognize it. I want my male readers to aspire to become godly men.

This is probably a general statement that may get me in trouble, but many of the sins that plague our world lay at the feet of men: human trafficking, prostitution, and pornography.

If men lived as they should, much of this would go away.

If we want to change the men of tomorrow,

we need stories that reach the boys of today.Tim shoemaker

We can help change the men of tomorrow by working to write compelling stories that show them what it means to be a good man. There’s plenty of fiction written for broken men, but this is our chance to write to boys before they’re broken.

Our future and their futures will be impacted by it. Writing books for boys is a noble, worthy task.

If a writer wants to do that, I’d advise them to keep working at it. Pray and ask God to help you. Get some boy readers to review a scene and ask, “Is this the way you’d do that?” Listen to their feedback.

Thomas: Imagine the impact on the world if we had a generation of young men who believe that self-control is real and that it’s possible to control themselves. What if we had a generation of young men who were not slaves to their desires?

That change can start with your stories.

If the fictional characters can’t master themselves and become self-disciplined, how on earth can readers do it in real life?

Show your readers how to overcome the struggle of self-mastery. It’s so powerful, and that’s just one element you can include in a transformative work for young men.

What about boys who don’t read?

Tim: Even though people tell you, “Boys don’t read,” I don’t know a boy who doesn’t love a good story. So even if they don’t read, you can read to them.

I’m always encouraging parents to read to their kids. I just got a letter from a mom who ended up reading to her 17-year-old, and it was so powerful. When you read to them, you can drop them into a story world, and they’ll start to love the story if it’s done well.

Connect with Tim and find out more about his books at TimShoemaker.com

Featured Patron

Bernadette Botz, author of Liar (Affiliate Link)

Written for Christian teens struggling with their faith, Liar is an allegory of the battle of good vs. evil.

You can listen to this episode How to Write Books Boys Will Love With Tim Shoemaker on Christian Publishing Show.