EDITORIAL

I need to clarify what I’m attempting to do with this series of posts. I am not digging deeper trenches and pouring the dirt over a head that is already buried in the sand. Some think I’m defending a dying industry and failing to see the changes around it. This series is merely an attempt to remind us what traditional publishers do well. Their critics are jettisoning all of traditional publishing as antiquated. But I posit that there is good to be found in the things that brought publishing to this place.

Today’s topic is Editorial – or more completely, “Content Development.”

Many critics say that the day of great editors is past. The legends are gone and instead we now have overworked editors who don’t have time to spend crafting and developing an author’s content into a masterpiece. They have become paper-pushers.

While editors are generally overworked…that is not anything new. It has been that way for a long time. While at Bethany House Publishers I managed the acquisition and editorial development of nearly fifty titles per year. But I did not work alone.

Editing is a multi-person process in the traditional publishing companies. First is the acquisitions editor who finds, defends, acquires, and negotiates the acquisition of a project (i.e. The Curator). Many times the actual content edit (also call the “line” or “substantive” edit) is done by a different person. The content editor looks for accuracy, balance and fairness, cogency of argument, adequate treatment of the defined subject matters and issues, and also includes conformity to all aspects of the description of the work contained in the original book proposal. (That sentence is an adaptation from actual contract language defining an “Acceptable” manuscript.)

Next comes the copy editor who scours the manuscript looking for accuracy in grammar, citations, and factual content. Then it is sent to a proof reader who scours the work for fine-tuned details in punctuation and other tiny details.

These editors are amazing people. And despite the cutbacks in many major publishing houses there are still a number of truly incredible men and women who stay behind the scenes and pour their minds and hearts into the books they work on.

In the Christian industry I’ll highlight one man as an example (and he will likely be embarrassed by this!). David Kopp is an exceptional editor with Waterbrook Multnomah. He was the one who created the eight million copy bestseller The Prayer of Jabez out of a nearly unpublishable massive manuscript. He worked on the bestseller Do Hard Things by the Harris brothers. And recently he helped transform a book about missions into what is now called Radical (by David Platt) that has been on the NY Times bestseller list for 43 weeks (as of this writing).

This is the type of talented person that sits unknown in an office in a traditional publishing house… helping to create magic. I could rattle off a dozen or more names off the top of my head of similar people who make this happen every day. And that does not include the number of freelancers who are hired by publishers to take up the slack when they cannot meet the demands of the editing process in-house.

A critic might say, “But I can just hire these freelance people myself. Why do I need a traditional publisher?” That is a good point. But it misses a critical part of the process. It is illustrated by the question, “Who pays the invoice?”

Think about it for a moment. In a traditional publishing house the publisher is basically in charge. If there is a major dispute over editorial changes or input, the publisher has final say and contractual clout. Rarely is this used as a hammer, but the writer always knows it is there. In almost every case there are long discussions and a compromise is achieved.

But when the author hires the editor, who is the boss? The writer is the boss. The writer will usually defer to an editor’s comments. But what if your novel is going down a terrible path, a path to commercial destruction? I know of a case where an author was bent on writing a particular storyline and would not take anyone’s advice. His agent was unsuccessful. His writing friends and critique partners could not sway him from the path. If he were self-publishing he would have failed miserably. Instead an editor at a traditional publishing house recognized the talent and came alongside with valuable suggestions. The author, realizing that the editor had the goal of creating a great book, acceded to the advice. The book was saved, is now in print, and being sold in stores everywhere.

I also know of another case where a freelance editor took an author’s manuscript (to be self-published) and rearranged the non-fiction content from a topical presentation to a chronological presentation. (The book was the history of a specialized type of job in our court system.) The editor felt that a history should be told chronologically instead of topically. The author disagreed and made the editor put it all back the way it was in the first draft. Because the author was “paying the invoice” the author’s wishes prevailed. The book did not sell and was not adopted as a textbook, which was the goal of the author.

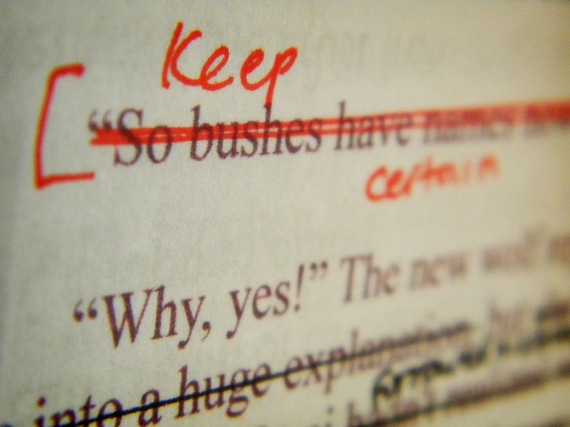

James Michener once said, “I’m not a good writer; I’ve been a masterful re-writer.” He has a fascinating book called James A. Michener’s Writer’s Handbook (1992). In this work are reproductions of the interaction between Michener and his editor. You can see the original text, the editorial suggestions, and the rewrite. A interesting exchange that is rarely seen.

As with the idea of “curation” I believe the editorial or content development process is a vital part of what a traditional publisher does for an author’s work.

As an aspiring writer, this is exactly what I want.

What I’m being told, more and more, is that editors want everything to be perfect. That I cannot send in a manuscript that needs any editing — which I know, no matter how much I polish, is impossible. If Michener needs editing, I need editing and always will. And I want that editing.

There are two competing messages: Editors don’t have time to make your work better, so it needs to be perfect. On the other hand, traditional publishers will improve your manuscript because of their fantastic editors.

I hope you see the disconnect.

I’ve never heard an editor say that a manuscript has to be perfect before it can be contracted by a publisher. Nor have I heard an editor say that a manuscript needs no work at all.

What you may be hearing is the writer’s conference challenge to make the book absolutely fantastic to that it is attractive to the editor and the publishing team.

There is no disconnect.

The idea that editors have no time is also incorrect. They have time, limited time, but it is also consumed by author relations, in-house meetings, etc. If the writer really amazing and needs little editorial attention, that much better for the editor and the publisher.

For example, a good editor could take today’s blog post and make it flow much better and prune extraneous words and even suggest a better thought flow. And I’m already an editor of dubious skill… 🙂

I’m on board with you, but the messaging we’re getting (mostly from agents) is that the book needs to be perfect.

I think I know what’s going on. 99% of submitted material is probably not ready for an editor to look at, much less an agent. Agents need to emphasize this and when they’re asked to put a number on it, “It has to be 100% ready” has a lot more force than “do your best.” I’ve heard agents say 100% ready.

The intent is to put the breaks on so many writers who are just not ready yet—so they improve their work—but the message is at odds with the intent. We hear “editors are strapped for time and want novels that need little to no editing.” The next thing we hear is that editing is the service publishers offer over self-publishing, well, there’s the disconnect.

It’s the difference between what is said and what is heard—and since the two are not the same, it’s a fine example of why we need editors

Steve, this is an excellent article. As a bookseller/buyer for 17 years I totally agree with everything you said. I’ve seen far too many self-published books that are poorly written and would have benefitted greatly from a good editor.

I enjoyed this contribution, Steve. Although my own five years inside the publishing industry were as a textbook editor, I can still verify that the manuscripts my authors sometimes thought were flawless and ready for press most often were far from it. A writer truly needs the perspective of a professional editor in the industry (not a high school teacher nor an English major at a community college) to provide the objective input necessary to hit the goal of producing a good, salable book.

Even an editor who also writes can benefit from another editor’s advice. Few authors (in my experience) are skillful enough and objective enough to play all the vital roles needed to produce a high-quality book from their own manuscripts.

Traditional publishing does offer its advantages, especially considering the role that agents and editors play in not only weeding out the “chaff,” but molding the products that do make it past their editorial eye. It seems that the villianization of the self-publishing world often revolves around the un-edited masses of marginally or completely unreadable muck. This leaves a bad taste in the mouths of the readership.

At some point I assume there will be a backlash. At some point the readership for self-published e-books will decline:

1) Readers will be inundated with the pure staggering volume of offerings available

2) Readers will tire of the sub-par writing and poor editing

3) Authors who have delusions of grandeur will have had their lesson learned, their crow eaten and be turning again to the traditional route of publishing since they turned little to no profit after paying for marketing, book cover art, and editorial services

For now though,the lure of self publishing is that e-publishing and POD publishing offer the immediate gratification authors crave.

I feel both forms of publishing have merit. Both have flaws. Smart authors will know when to use each to their advantage. It depends on your market, your audience, your ability, your patience and your professionalism. If all you want out of your writing is to “be published,” then self publishing can be a viable vehicle for your work. Your validation (or disappointment) will lie in your success (copies sold).

Robert,

A very thoughtful comment. Thanks for adding to the discussion!

Unfortunately the lure of DIY (do-it-yourself), especially in ebooks has become quite strong. The news of novelist Barry Eisler turning down a $500,000 advance for a two book deal so that he can self publish using J.A. Konrath’s methods is pretty substantial news.

Konrath himself thinks that anyone going the traditional route is “dense.” (http://jakonrath.blogspot.com/2011/04/are-you-dense.html)

One of the most important days of my life was when I realized I wasn’t as smart as I thought I was. I wished that happened somewhere around the time the doctor spanked my bottom, but unfortunately my delusion tarried.

Now, realizing and embracing my weaknesses and many blind spots when it comes to my writing, I’m relishing the time spent in dialog with fellow writers, agents and editors.

No…the institution some seem anxious to tear down is not shadowy hallways with rows of computer servers. Instead, it is replete with people of talent and personality, which I believe are critical to the literary process. You can circumvent this, but in my opinion, you should be aware of what will be lacking and should be replaced.

Thank you for detailing the process of our precious MSS’s trip through the editorial office. This allows us writers to gain perspective on the benefits of traditional publishings editorial team concept.

Glad you mentioned David Kopp. He’s the best in the business. A real writer’s-editor who understands the big concept of a book, what readers want, and how words flow onto a page.

Well…! I just enjoyed David Kopp’s morning track at the Mt. Hermon Christian Writer’s Conference. He really is a remarkable guy. But so are you, Steve. I really appreciated your penetrating insights. They were far more than bricks wrapped in velvet. They were gifted insights wrapped in years’ worth of wisdom. Thanks for what you do in the publishing world.

Great series on the merits of traditional publishing. As long as we have such dedicated people working for beautiful and precise writing, I have hope.

Every time I’ve worked with writers who knew more than I did, my writing rose to another level. I look forward to that time when I can work with an editor at a publishing house; I expect it will be even more eye-opening.

One thing I worry about in the back of my mind is that I’ll end up working with a sub-par editor for my first publication and they’ll massacre my work. Several facts support my fear: I’ve read poorly edited novels, I’ve read accounts of publishing houses having differences of opinions on writers or projects that eventually were successful, I’ve had chapters critiqued by freelance editors where they didn’t understand something my eleven-year-old would.

So my question is this: when do you know if your editor is wrong and how should a writer respond?

I believe there is great value in editing, but so often the implication is that authors don’t really know what they are doing, but editors do. I suppose there may be some truth to that because most of us are hobbiests who aren’t English majors, but it is the author’s name that goes on the cover. Suggestions should be welcome, but ultimately, it is the author who takes the heat. We can’t assume that the book that didn’t sell well is because the author rejected the editor’s suggestions or that the prayer of Jabez book sold well because of editing. It may be true, but I’ve seen manuscripts that were better before the editors got their hands on them. Like in many professional situations, this seems to be a case where you think your side, whichever side that is, can do a better job than the other, if they would just let you.

Great post. I want traditional publishers to hang around. Publishing has for a long time been a team effort. And I don’t think the stories (regardless of whether we read them on a page or screen) are going to be improved by removing most of the team. If an author has to do all of her own editing, distribution, and marketing and work at a harder, better-paying day job because she gets no advance, then the story is going to suffer.

Your point about who has the final say is a good one. I hadn’t thought about it before. I’m about to go on submission to publishers and I’ve been praying that if my book sells it will get a great editor.

Here is a fantastic piece from Robert Gottlieb, one of the greatest editors of our generation (he makes my point in the last anecdote…):

Editing is in the details.

It is, but it’s also in the overview. It’s both. You have to be able to see a book as a whole, and then you have to step forward and scrutinize.

When I was at the New Yorker I edited a number of pieces, but when I think of myself as an editor, it’s as an editor of books. Sometimes, if you’re lucky, a manuscript is perfect; you don’t have to do anything except say, “Great, well done!” and send it on its way. Sometimes, the problems are cosmetic, and you just have to be careful and point out where the language goes wrong and where there’s a contradiction or repetition — as I say, surface things. But sometimes the problems are structural, and the book just isn’t making sense as written. Then one has to sit with the writer and try to figure out how to make it cohere. Other times, alas, there’s just no book there. That’s a problem. Because, as I like to say, You can take it out, but you can’t put it in.

And then there are times when it’s just a matter of too much, and you have to convince the writer where it’s too much and why it’s too much — perhaps because there’s an imbalance. Often, it’s a question of the beginning and the end. Sometimes a book starts awkwardly. The writer hasn’t revved up and it’s stilted. You have to say, “You know, drop the first two paragraphs and you’re fine.”

Much more radically, when I was first presented with the manuscript for a novel that became a huge bestseller and is still a much-loved book, Chaim Potok’s “The Chosen,” I was reading it and loving it until I got to a point where I wasn’t loving it. I went on reading another 300 manuscript pages or whatever and then called up the agent and said, “I absolutely love this but it’s not publishable as it is. Could you tell the writer that I’d be happy to edit and publish it, but only if he grasps that the book ends here, but he’s gone on and written a second book. And they don’t belong together.” Luckily, Chaim agreed.

http://www.salon.com/books/laura_miller/story/?story=/books/laura_miller/2011/04/26/robert_gottlieb_interview

Whoosh. Succinctly stated, and I love the real-life clincher at the end.

Thank you for your overview of the importance of thorough editing, Steve. Often, an author can take advantage of the services of both a freelance editor (to help the author get his or her manuscript in shape) and the publishing house’s editor(s). The key to working with any editor is having a teachable spirit.

I recently edited website copy for a person who was starting a business. The copy was wordy and rambling, so I tightened it. Then the client lengthened it. We went back and forth at least 7 times until we agreed that the copy was ready to publish.

After the client’s site launched, I visited it to see how it had turned out. The client had published the original, unedited version of the copy on her site! Her website, while designed beautifully, is riddled with spelling errors and sounds as if a fifth grader wrote it. The client was so in love with her own words that she was unwilling to listen to direction from the professional she hired to help her improve her writing.

It still mystifies me.

I didn’t realize all the different editors involved. Thanks for the insight, Steve.

It’s encouraging to know how many people, besides me, will have a stake in making my book the best it can be. I welcome that. Although I want to know where and how it can be made better, I’m also a constant tweaker who sometimes needs to hear, “Enough already! You’ve got it.”

(Phew! Easy math today.)

I’ve been having lots of discussion about this on my blog, too. Preparing to Kindlize one of my traditionally published books, I still found errors. Even after all those editors vetted it.

I got steered here by Hope Clark. You have very important things to say. Newbies are throwing unedited first drafts out there with such abandon, I fear good books will be lost in the pile of bad ones.