Are you starting your book in the wrong place?

I’m not referring to giving too much backstory. I mean, are you starting your story in the wrong place? Pantsers often start at the beginning and just let the story unfold. Plotters often want to outline the entire story from beginning to end before they write the first page.

But what would happen if you started writing your book from the middle?

Believe it or not, it could change everything.

James Scott Bell teaches that approach. He’s an award-winning thriller author, and he’s also very well known for his bestselling craft books.

What does it mean to write your novel from the middle?

Thomas: Let’s talk about your most controversial and influential book, Write Your Novel From the Middle (affiliate link). What does it mean to write your novel from the middle?

James Scott Bell: I started out as a screenwriter, where structure is ingrained in you from the beginning. That deep dive eventually led to my book Plot & Structure (affiliate link), which has been in print since 2004.

For a long time, I didn’t think there was anything particularly special about what people call the “midpoint” or “midpoint scene.” I found a lot of contradictory advice. Some teachers said it was a moment of facing death, but others described it differently. There was no consistent pattern that made sense to me.

Several years ago, I decided to study it for myself. I pulled out DVDs of my favorite movies and some of my favorite novels, and then I went straight to the middle of each one. I wanted to see what was really happening at the midpoint.

I made the surprising realization that the midpoint wasn’t always a full scene. It was often just a moment within a scene, but it kept landing right at the center. In that moment, the character would have a confrontation where the character would take a hard look at themselves. I came to call it the “mirror moment.”

It blew me away how often it happened. I started applying the concept in my own writing, and it worked incredibly well. Then I began teaching it to others, and it worked for them too.

Thomas: I recently recorded a Novel Marketing episode on chiastic structure. It’s an Eastern two-act form often used in anime and frequently found in the Bible. I haven’t been able to get a clear answer on how many chiasms are in Scripture. Most theologians just say “thousands” and leave it at that. Many chiasms are nested within each other, especially in the Book of John.

In the anime version of the chiastic structure, the midpoint is what my brother David calls the cataclysm. It’s usually the most important moment in the story, whether it’s a multiseason series or a single arc. It changes everything and often occurs right in the center. In anime, it’s usually both internal and external.

In fiction, especially novels, I think it’s easier to make that moment purely internal. Novels take place in the theater of the mind, so you explore a character’s thoughts. Screenwriting relies on visuals and doesn’t show internal dialogue. In novels, you can explore those shifts directly.

This central moment is often about recognition. The character realizes something is wrong. They either confront a major personal flaw or realize the odds against them are so great that their survival is uncertain.

James: For example, I usually turn to Casablanca first. Right in the middle of the movie, there’s a key moment: Ilsa returns to the bar after Rick has seen her. (Every writer should watch this movie.)

She comes back to explain why she had to leave him. Rick feels betrayed. He’s drunk and ends up insulting her. She cries and walks out.

Then Bogart gives this powerful look of self-loathing. He lowers his head. It’s a visual moment. We see him facing himself and not liking what he sees. In a book, you can explain that moment internally. You can describe what’s happening in the character’s mind. The rest of the story is about whether this character will change. Can he overcome that flaw, survive, and become a better person?

Thomas: Let me give an example from a children’s book. One of the most well-known children’s books of the 20th century is Goodnight Moon, which follows a two-act structure. The shift in the story happens with the phrase “Goodnight moon.”

In the first part of the book, the child is describing everything in the room. Then comes the line “Goodnight room,” and everything changes. The child moves from calming down to falling asleep. Each scene becomes progressively darker. Instead of describing objects like the telephone, the child begins saying, “Goodnight, telephone.”

As a parent of young children, I’ve heard my wife jokingly refer to this as “goodnight pointless sleep-time rituals everywhere.”

This structure works just as well for thrillers as it does for children’s books. What the turning point (or cataclysm) is depends on the genre.

In Casablanca, it centers on Bogart’s character. Is he a good man? Was he always a good man, or has he been the villain all along? His future actions will shape how his past actions are understood. His morality is on the line.

In Home Alone, there’s a powerful moment a little past the halfway mark where Kevin goes to church, sees an older man, and they confess their sins to each other. They both experience a moment of repentance. Kevin then decides to defend his home. He stops running and starts fighting the bad guys.

The first shift is earlier in the movie when Kevin decides not to be afraid anymore. The second is his realization that he needs to repent, forgive his family, and that his home and family are worth fighting for.

James: Genre is a factor in creating that mirror moment. In my view, stories that really work are about characters facing some form of death. That could be physical, psychological, spiritual, or even vocational. The stakes need to be high so that readers care.

At the midpoint, during the mirror moment, the confrontation is often with psychological death. That’s what we see with Bogart’s character. Will he keep going down a path of self-destruction and isolation, refusing to help anyone? Or will he rejoin the world and change?

In many thrillers, though, the protagonist doesn’t change. There’s no major character arc. Jack Reacher is a good example. He’s the same at the beginning and the end. So what changes?

Consider Harrison Ford’s character in The Fugitive. He’s a decent man at the beginning and the end. The midpoint isn’t about internal transformation. It’s about survival. In the middle of the story, he realizes the odds are overwhelming. He thinks, I’m going to die. I can’t possibly survive. The rest of the story is about how he does.

The same pattern shows up in The Hunger Games. That first book is focused on survival. If you flip to the middle, there’s a moment where Katniss thinks, This is probably a good place to die. Then, the next major event hits.

So, whether it’s a confrontation with personal flaws or the realization that death is imminent, those are the two core types of mirror moments. In a cozy mystery, for example, that midpoint might be the most devious, Moriarty-style twist yet. The tone is different, but the structure still holds.

Thomas: When you place your mirror moment (cataclysm or peripety) at the center of your story, it transforms what could be a sagging middle into one of the most memorable parts.

Take The Hobbit, for example. The chapter “Riddles in the Dark” is the turning point for Bilbo Baggins. It’s his mirror moment. He’s underground, cut off from all light, hope, and friends, and he’s facing death. At that moment, he finds the ring. More importantly, the few strengths he has are tested and used. He shifts from being passive to active.

Up to that point, Bilbo has been a whiny, reluctant tagalong, mostly there to prevent the group from having the unlucky number 13. Some say his transformation happens because of the ring’s power. While the ring is a symbol of that change, it’s not the source of it. The true shift is that Bilbo chooses to become useful and courageous.

If you connect The Hobbit to The Lord of the Rings, Bilbo’s mirror moment in “Riddles in the Dark” parallels Frodo’s at Mount Doom. In Bilbo’s case, he sneaks up behind Gollum and chooses mercy. In Frodo’s case, Gollum comes up behind him, bites off his finger, and saves him. The parallel is striking and symbolic. It shows how the choices we make ripple through generations. It’s a powerful thread.

James: The mirror moment at the midpoint acts as a powerful linchpin for the reader. It subconsciously connects them to the deeper, underlying story of what the book is really about. It engages them in a powerful way.

As a writer, whether you’re a plotter or a pantser, the beauty of the mirror moment is that you can brainstorm it at any stage of the writing process. When you explore a few possible ideas, one of them often clicks. It’s that moment when you realize, “This is the story I’m trying to tell.”

Once you find it, everything else starts to fall into place. The beginning and ending naturally align, and you stop writing yourself into dead ends. It becomes a guiding light that helps you shape the entire book. It’s an incredibly useful tool.

How does morality affect the mirror moment?

Thomas: The two-act structure turns a book into cause and effect. It builds to either a good or bad decision, depending on whether it’s a comedy or a tragedy. The character doesn’t have to make the right decision. Bilbo could have killed Gollum in the cave, and it could have been a tragedy, as wickedness burned its way through his soul for the rest of the story.

Morally speaking, tragedies can still carry a powerful message. Clear morality in storytelling is one of the things that really makes stories work.

Hollywood is struggling right now because the morality in so many of its stories is so broken.

James: The Greeks used tragedy to teach morality, and it was a powerful tool. One example I use in the book is The Godfather.

We often think of a character arc as someone going from a negative place to a positive one, like Rick in Casablanca, who recovers and chooses to do the right thing. But the arc can go in the opposite direction too.

In The Godfather, that’s exactly what happens. Michael starts out as the good, smart, legitimate son. After the attempted assassination of his father, he has to choose whether he will ignore the family business, as everyone wants him to, or if he will do what needs to be done.

He knows that once he makes that choice, his life will change forever. By the end of the story, he has lost his soul. That’s the message of The Godfather.

Thomas: It’s a powerful message, and it’s important for us to be reminded of the wages of sin in storytelling. We know that truth intellectually, but what are the wages of this specific sin? Sometimes, a specific sin doesn’t seem so bad. But you can work that into a story by showing characters sinning and repenting, and it becomes really powerful.

This is part of why Narnia is so resonant. The children are dirty, rotten sinners. Most of them have a lot of repenting to do. Even Lucy has to repent. They’re not perfectly virtuous characters, but the story is still a moral story.

As Christian storytellers, we don’t want to tell Hallmark stories where there’s no real sin. We live in a fallen world, not a Hallmark world where people are simply misunderstood. Too much of that creates a distorted morality; and that can lead to a distorted religion, where people reject Christianity in favor of a “be nice” morality. But that’s not true morality.

James: Somebody once said that as writers, “We don’t write reality. We write seductive believability.” It’s the believability part that reflects the truth.

We want to draw people into the story, so they can truly experience it. That’s what catharsis was for the Greeks. When readers feel the full range of emotions through a story, that emotional experience becomes the real connection.

It’s not just about plot twists or quirky characters. Some writers are losing sight of that, especially when using AI as a writing partner.

What happens after the mirror moment?

Thomas: The mirror moment is this cataclysm in the center of the story, where the character faces death and makes a key decision that changes everything. You talk about this as a suspension bridge with a pole in the middle of the story.

James: The second half of the story explores whether this character will be able to solve this particular problem. The scenes you write force the character closer to having to have that final battle within themselves or with the outer forces. Sometimes it’s both. In Star Wars, Luke confronts himself, finds courage within, and then fights the physical battle.

The second half of the story is a buildup to what I call “the second doorway of no return.” There are two doorways of no return. The first is what some people call the first plot point. I prefer “doorway of no return” because it more aptly describes what should happen.

The protagonist is being pushed toward the death stakes. They don’t want to go through that door, but something pushes them through.

Then, before you can wrap things up, there has to be some kind of major clue, discovery, or setback that forces the last act, such as when Dorothy was captured by the flying monkeys in The Wizard of Oz. That’s a huge setback that forces the rest of the story to happen.

The final beat of the story is “proving the transformation.” It’s a scene that shows that the character has overcome. In the end, the character becomes a new person, a new iteration of themselves, a better person; or, in rare cases, they become worse. Sometimes, they become stronger. In each case, the character’s transformation is proven.

Thomas: This is deeply theological. It’s the testing of your faith that produces perseverance. It’s the testing of the seeds to see if they’ve landed on good soil. Did the seeds of that decision fall on the hard path? Among the thorns? On rocky ground? Or on good soil? Only through testing can that be revealed.

As an author, you have to test your characters. You must make them confront the demons in their own soul and their sinful nature. You have to challenge them. If life is too easy, you’ll never know if the change they experienced or the mirror moment they had was real. Is the child really falling asleep at the end of Goodnight Moon?

Another great example is The Cat in the Hat. The Cat arrives, and chaos ensues. Sometimes, the mirror moment doesn’t fall exactly in the middle of the book in terms of pages. Instead, it falls in the middle in terms of plot. That’s common in many stories. Midpoints tend to show up a little later because you first need time to introduce the world, the stakes, and the characters before the real plot kicks in.

In The Cat in the Hat, the mirror moment comes when Mom is on her way home. Suddenly, the children shift from watching or whining about the mess to taking action. They must decide: Are we going to clean up this disaster? What are we going to do now that we’ve trashed the house?

The story ends exactly where it begins, but with the question “Are we going to tell Mom?” That ending is brilliant because it turns to the reader and asks, “What would you do if your mother asked you?” It invites children into a conversation with their parents, giving them a safe way to talk about the strange things they see adults do. That’s powerful.

It’s a masterpiece and one of the bestselling children’s books of the 20th century. Great midpoints help turn bestsellers into classics because they anchor the story in timeless moral questions, rather than zeitgeisty hot takes. Questions about temptation, truth, and sin are always relevant.

Neither The Cat in the Hat nor Goodnight Moon depends on the zeitgeist. Kids making a mess, being left alone, and encountering odd adults are universal experiences. That’s why these books continue to resonate with children, parents, and grandparents across generations.

James: The mirror moment is what elevates merely competent fiction into unforgettable fiction. That is the real demarcation line today. There’s so much competent fiction. Bots can spit out competent but empty fiction.

I’ve been reading some of these bot-generated novels people are putting out, and it is so obvious to me how empty it is. The writing is competent, and the sentences make sense; but the heart is missing.

I teach writers to get to that next level through the mirror moment because that is what will set you apart in this roiling tsunami of content.

Thomas: Often, the middle of a three-act story is the weakest part. It tends to sag, losing momentum and focus. But if you can turn that weakest point into the strongest moment by making it the cataclysm or mirror moment, it transforms the whole story.

My father once inherited an old, rundown fishing shack that had belonged to his great-grandfather. It was easily the worst house on the street. The question was whether it was worth saving at all. But he put time and effort into renovating it; and, suddenly, it became the nicest house on that little road.

But only for a year. Once he fixed it up, all the neighbors started renovating their homes too. They didn’t want the old fishing shack to look better than theirs.

That’s what happens when you take your story’s sagging middle and strengthen it with a powerful mirror moment. It becomes a force that pulls the rest of the story up with it. As you revise, the beginning and ending are drawn to match that energy, creating tension and cohesion that carries through the whole book.

James: Your scene ideas cease to be random. Instead, they have organic unity. You’ll find you have a through line, and it’s just a matter of you choosing the scene that will best exemplify what you’re trying to say. I think it makes the task a lot easier.

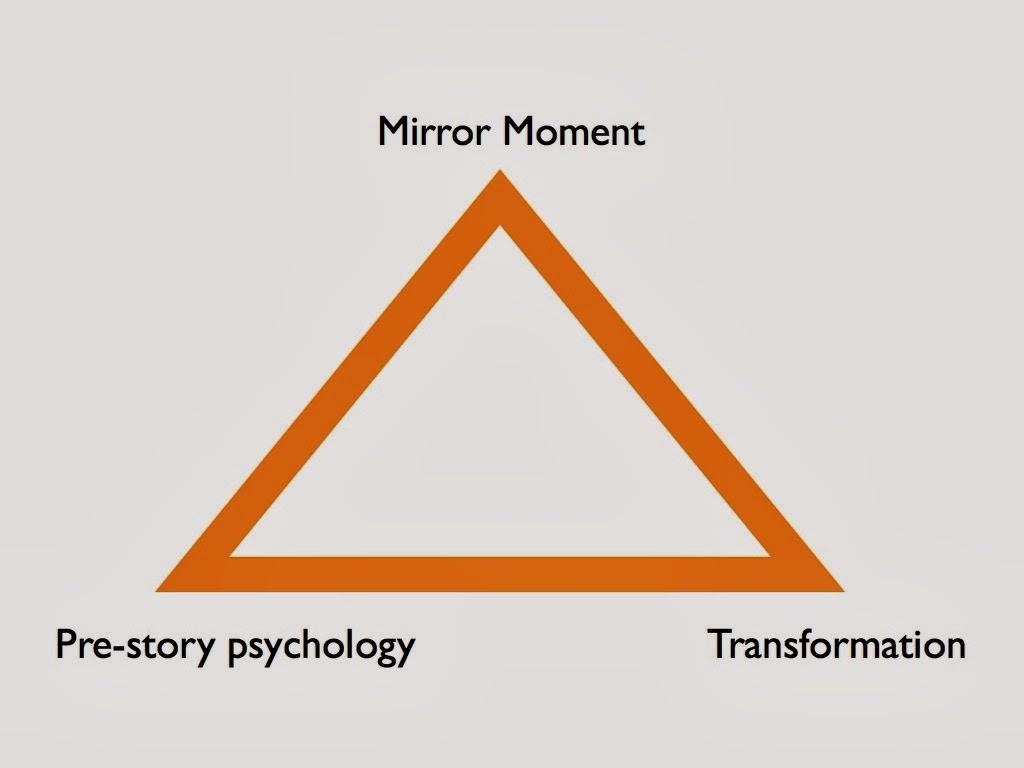

How does “The Golden Triangle” relate to the mirror moment?

Thomas: In your book, you talk about “The Golden Triangle.” How does it relate to what we’re talking about with the mirror moment?

James: The triangle is the strongest structure in nature. Thomas R. Buckminster Fuller, the inventor of the geodesic dome, used this principle. Those domes are made entirely of triangles because each one reinforces the others. The Golden Triangle represents the strongest story structure.

The first point at the base of the triangle is the prestory psychology, or who your character is before the story begins. The top point is the midpoint. The final point, on the other side of the base, is the transformation. These three points are what I emphasize, and the beauty is that you can start with any one of them to build your triangle.

You might start with the transformation, thinking, I want to write about a person who goes from this state to that one. Then you can ask, “How would they get there? What’s the moment that signals their need to change?” You might begin by brainstorming the midpoint. Once you have those pieces, you can go back and define the prestory psychology that fits.

Sometimes, writers begin with a fully developed character and a long backstory. But that’s always the best approach. You may not yet know what story you’re trying to tell or what kind of character fits it best. For me, the background usually comes later.

This triangle framework helps you focus on the three major points that hold a story together, giving it a solid structure that feels complete and grounded.

What do you mean by the “transformation”?

James: At the end of a story about a person confronting their own humanity, we need to know the transformation has really happened.

I call this “proving the transformation.” We need a scene that shows us the change. We need to see Scrooge walking down the street with Tiny Tim. We need to see him buying the prize turkey. It has to be shown, not just implied.

In all great films and stories, there’s usually a moment, either the final scene or the one just before it, that confirms the transformation has taken place.

One of my favorite examples is Lethal Weapon. It’s a great thriller with a strong psychological component. Mel Gibson plays Martin Riggs, a suicidal cop whose wife has died. He throws himself into danger because, deep down, he wants to die. His recklessness makes him an incredibly effective cop, and it scares the criminals.

He’s partnered with a calm, steady veteran cop played by Danny Glover, who’s about to retire and just wants to keep things under control. At one point, they have a powerful confrontation. Glover accuses Riggs of acting crazy to get a psycho pension. Riggs responds by pulling out a hollow-point bullet and telling him, “I carry this around, and every day I have to find a reason not to blow my brains out.” They have a heated fight.

But at the end of the movie, after Riggs has saved Glover’s family, he comes to their house on Christmas. Glover’s daughter answers the door, and Riggs hands her the bullet with a ribbon tied around it. He says, “Tell your dad I won’t be needing this anymore.”

It’s a beautiful visual cue. That single moment shows us he has changed. He’s no longer the man who wanted to die. He’s become the man he was meant to be. He has been delivered from the living death he was living.

How does the classic “return home” prove the character’s transformation?

Thomas: One really effective way to prove a character’s transformation is to bring them back to where they started at the beginning of the story.

For example, in The Lord of the Rings, the hobbits return to the Shire. When you’re surrounded by Balrogs, Nazgûl, and humans, it’s harder to see how much the hobbits have changed. But when they go back to a place where the biggest concern was a birthday party guest list, their transformation becomes much more obvious.

This ties into the chiastic structure, though it doesn’t have to be formally chiastic. In the hero’s journey, this is known as the “return home.” It’s a powerful way to show their growth, but it doesn’t have to be a literal return home. In Lethal Weapon, for example, Riggs going to his partner’s home at the end of the movie serves the same purpose. It shows who he has become.

There are other ways to show transformation; and sometimes those may work better, depending on the story. But the simplest, most reliable method is bringing the character back to the beginning.

We see this in The Cat in the Hat. The book starts with the children sitting and looking out the window, and it ends the same way. The image is nearly identical. But now, they’ve experienced something big. They have a secret. Do they tell their mother? That’s the transformation. That’s the moment you talk about.

Bringing them back to the beginning is one of the clearest ways to show how far they’ve come.

James: You mentioned the mythic structure and the return with the elixir. The elixir is the thing the hero learns and needs to survive the journey through the dark world.

Your story ends with the implied elixir. I call it “the life lesson learned.”

One exercise I give my students is to imagine their character 20 years later. Interview that character and ask, “Why did you have to go through all of that? What message do you have for us?”

That answer becomes the life lesson. Then, you find a way to show that visually at the end of the story.

Casablanca is a perfect example of this.

Thomas: You also see this in Star Wars with Luke’s return to Tatooine. He starts out as a whiny farm boy when he leaves; but by the time he returns, he’s undergone a major transformation. He’s now a Jedi Knight. He still has things to learn, but he’s no longer that same uncertain kid. He’s stepped into his role.

That change becomes very clear when he comes back to Tatooine to rescue his friends. Earlier in the story, his friends were rescuing him. Han Solo pulled him out of danger from storm troopers. Now, the roles are reversed. Luke returns to rescue Han, who’s been frozen in carbonite.

How do you approach that prestory psychology?

James: When you know what the transformation is, you can go back and identify “the lack” or what the character is missing at the beginning of the story.

In Casablanca, what does Rick lack? What in his background caused him to become the isolated, uncaring man we see at the start? In the movie, we get the answer through a flashback that explains it.

As a writer, you can create a major event from your character’s past that caused this lack. It’s something that directly connects to what they will confront in the mirror moment.

That’s where brainstorming comes in. You write what fits. In my experience, it’s easier to add backstory once you get the story going and the character moving through their journey. Starting with backstory can sometimes lock you into something too early.

That said, everyone works differently. You might prefer starting with the backstory, and that approach might help you brainstorm an entire book. Either way, what you’re really identifying is the moral flaw or moral lack at the beginning of the story.

Then, in the opening scene, you show the character living out that lack; and that sets the stage for everything to come.

Thomas: That’s a much more efficient way to write a book. You’ll likely finish more books in a year using that approach. If you start with backstory, how do you know which parts are relevant? You’ve got a 30-year-old character. Is their time in elementary school important? Middle school? Their first boyfriend or girlfriend? Most of that is probably irrelevant.

You can waste a lot of time generating biographical details that never make it into the story.

The same goes for world-building. What parts of your fantasy world matter to the story? You can create entire regions or histories that are simply alluded to. Think of Gandalf in The Fellowship of the Ring when he says there are unmentionable things deep underground. That’s all he says, and it works. Of course, Tolkien may have written full backstories for those creatures; but he didn’t need to include them.

Tolkien didn’t write many books because his method of world-building and backstory was so detailed. It wasn’t efficient.

By focusing on what your character needs for the story, you can build just enough backstory to make them work. If you discover later that something’s missing, you can always add it during revisions. But you’ll never get that backstory-writing time back. All that drama you wrote about a middle-school science teacher might end up being completely irrelevant, and now you’ve spent hours building a conflict that never mattered.

Is it world-building, backstory, or procrastination?

James: I think all that backstory and world-building you’re talking about can sometimes be a form of avoidance. When you’re unsure about your story, and you’re feeling a little hesitant, it’s easy to spend time writing character histories or building the world. It’s fun, it feels creative, and it starts to come alive.

That kind of writing is often a way to avoid diving into the heart of the story that really matters. And that’s the part you can more easily adjust and refine as you go.

Thomas: We sometimes think, My editor won’t criticize me for a backstory that never makes it into the book, so I’ll just write that instead of something that might actually get critiqued. Fear may be causing you to avoid writing the story.

Authors are very creative at renaming fear. We call it writers block. We call it working on backstory. But the truth is, it takes courage to write. Some writers hide behind vague or flowery language instead of saying what they really mean. It’s safer.

It takes courage to write a story that might offend someone. But if your story doesn’t offend anyone, chances are it won’t deeply move anyone either.

It also takes courage to submit your work and to pitch agents and publishers if you’re going the traditional route, or to publish on Amazon and start getting reviews if you’re going indie. Writing is courage all the way down.

There are all kinds of ways to make cowardice feel like something noble. You tell yourself, “I’m not avoiding. I’m working on my backstory.” Maybe you are, but maybe you’re avoiding it.

Cowardice is unappealing in characters and in ourselves. No one is proud of being a coward. There’s no culture in the world that celebrates cowardice. Courage is doing what’s right even when you’re afraid. It’s universally admired.

So, be universally attractive to yourself. Have courage. Just write. You can always fix it later.

How do you write an ending worthy of that middle point?

James: I work on the endings of my books more than any other part. I even wrote a book called The Last 50 Pages (affiliate link) about the art and craft of unforgettable endings. It’s not just about tying up plot threads or resolving character arcs, it’s also about the resonance of the language itself.

When you read the final line of a great book, it leaves you with that lingering, awed feeling, like the last line of To Kill a Mockingbird, and it’s moving. That’s what I’m aiming for. It’s not just the logistics of wrapping things up. It’s the sound of that final line.

There’s no strict craft formula for achieving that. It comes from your voice and your heart. That kind of writing can’t be done by AI or a machine. If you can leave readers with that emotional echo that resonates like the final note of a great symphony, then you’ve done something truly memorable.

It’s not easy, but it’s worth striving for. What I often do is write a last page, then try another version. I look for that perfect line of dialogue. I say it out loud. I test the rhythm. I do everything I can to get the sound just right.

When it clicks, it’s like that final chip on Michelangelo’s David. You step back and think, Yes, that’s it. One last touch; and, suddenly, it becomes a classic.

Learn more about How to Write the Last 50 Pages of Your Book with James Scott Bell.

Thomas: You want your ending to resonate with both the midpoint and the beginning since they are the two anchor points of your story’s “suspension bridge.” That resonance gives the ending emotional weight for the reader.

It’s not enough for the story to simply build and build until the hero shoots the bad guy at the end. That kind of ending is forgettable unless that final moment ties back to the midpoint and to who the character was at the beginning of the story.

That’s why the bullet with the ribbon around it in Lethal Weapon is so powerful. The movie opens with Riggs contemplating death, holding that bullet, and grieving his wife. The midpoint features him telling his partner about the bullet, and the ending ties it all together.

Writers can see why that ending works. Readers may not consciously know, but they feel it. It’s like the structure of a house. You can’t see the two-by-fours behind the drywall, but you know the house is strong. It doesn’t wobble when you walk through it. It holds up in a storm.

That’s what good structure does. It supports everything, even though it’s invisible.

James: In my book on structure, I talk about “the argument against transformation.” This happens early in the story, where the character pushes back through words or actions against the very change they’ll ultimately undergo.

By the end of the story, the character has transformed. They’ve learned the life lesson. They’ve gained the elixir. But at the beginning, there’s usually a moment where they argue against that future version of themselves.

In Casablanca, Rick repeatedly says, “I stick my neck out for nobody.” That’s his argument against transformation. So when we reach the mirror moment at the midpoint and finally see him act selflessly at the end, it resonates with the audience. That early statement has been carried all the way through, and in the end, it’s resolved.

Or look at The Wizard of Oz. At the start, Dorothy believes there’s a place over the rainbow where there’s no trouble. Her argument is that she needs to escape to that place. But after her journey, she says, “There’s no place like home.” That’s the opposite of where she started, and it completes her transformation.

You’ll find this in so many great stories. Look for the moment early on when the character is living, doing, or saying the opposite of who they will become. That contrast creates a powerful emotional connection for the reader.

Connect with James Scott Bell

Substack: Whimsical Wanderings. Humorous writings purely for the entertainment of the reader.

I LOVE CHIASTIC STRUCTURE!

Half my writer friends have no idea what I’m talking about when I say that. I first learned about it from K.M. Weiland, but I’ve used it subconsciously in my stories for ages. That feeling when the ending ties into the beginning is AMAZING. It’s what turned me into a plotter XD.

It was actually what hooked me into The Green Ember. That first line, when you read, “It was Heather who invented the game, but Picket made it magic…” you sit there going OH BOY WE ARE GOING TO COME BACK TO THATTTTT. And we did and it made for a gorgeous ending of The Green Ember series. It just instilled this feeling that things were peaceful now, but one day they would not be so.

Ironic that you should write this when my main reason for writing my first draft far faster than my average rates is because I recently fleshed out my midpoint more and I am VERY excited to get to it (I love midpoints in general, but I figured out how to include this big character arc gut punch aspect that just… ahhhhh my readers will hate me but it’s going to be so powerful). I’ve been keeping chiastic structure in mind with everything I’ve been plotting in this duology, down to the first and last lines of the first book’s prologue and the last book’s epilogue. I could probably ramble all day about how much I love this structure and I’ve used it in just about all of my novels, along with Weiland’s Three Act structure.

I wonder if God saw my life

as growing from the middle,

starting with career and wife,

then moving to unmask the riddle

of the necessary growing,

and inevitable end,

all the while well-knowing

that the middle was the bend

in the road for Providence

to set His wheels in motion,

the place where I would notice whence

came Love, and His devotion

and thus set me on the way

to the man I am today?

Wow! I just finished outlining a story I’m rewriting last week and implemented so many of these principles…BEFORE I knew they were principles!!!

Thank you for validating the structure of my story! I can’t wait to write it now!

I love this post. James Scott Bell’s book “Write Your Novel from the Middle” had a huge impact on me when I started working on my second novel, and the concept is always in mind when I’m writing.

The examples are excellent. I always think of the movie “The Spirit of St. Louis” when I think about the middle moment. The movie is the story of Charles Lindbergh’s famous flight from New York to Paris. Right in the middle of the movie is the scene where Lindbergh has to decide whether or not to take off. Everyone thinks he should wait. He didn’t sleep the night before, and the weather and take-off conditions are horrible. James Stewart plays the role of Lindbergh to perfection, and you can see the doubt in his eyes when he makes the decision to go. (There’s even a mirror in the scene which I doubt actually occurred, but some clever script writer probably thought it would be clever to include it.)