EDITORIAL

I need to clarify what I’m attempting to do with this series of posts. I am not digging deeper trenches and pouring the dirt over a head that is already buried in the sand. Some think I’m defending a dying industry and failing to see the changes around it. This series is merely an attempt to remind us what traditional publishers do well. Their critics are jettisoning all of traditional publishing as antiquated. But I posit that there is good to be found in the things that brought publishing to this place.

Today’s topic is Editorial – or more completely, “Content Development.”

Many critics say that the day of great editors is past. The legends are gone and instead we now have overworked editors who don’t have time to spend crafting and developing an author’s content into a masterpiece. They have become paper-pushers.

While editors are generally overworked…that is not anything new. It has been that way for a long time. While at Bethany House Publishers I managed the acquisition and editorial development of nearly fifty titles per year. But I did not work alone.

Editing is a multi-person process in the traditional publishing companies. First is the acquisitions editor who finds, defends, acquires, and negotiates the acquisition of a project (i.e. The Curator). Many times the actual content edit (also call the “line” or “substantive” edit) is done by a different person. The content editor looks for accuracy, balance and fairness, cogency of argument, adequate treatment of the defined subject matters and issues, and also includes conformity to all aspects of the description of the work contained in the original book proposal. (That sentence is an adaptation from actual contract language defining an “Acceptable” manuscript.)

Next comes the copy editor who scours the manuscript looking for accuracy in grammar, citations, and factual content. Then it is sent to a proof reader who scours the work for fine-tuned details in punctuation and other tiny details.

These editors are amazing people. And despite the cutbacks in many major publishing houses there are still a number of truly incredible men and women who stay behind the scenes and pour their minds and hearts into the books they work on.

In the Christian industry I’ll highlight one man as an example (and he will likely be embarrassed by this!). David Kopp is an exceptional editor with Waterbrook Multnomah. He was the one who created the eight million copy bestseller The Prayer of Jabez out of a nearly unpublishable massive manuscript. He worked on the bestseller Do Hard Things by the Harris brothers. And recently he helped transform a book about missions into what is now called Radical (by David Platt) that has been on the NY Times bestseller list for 43 weeks (as of this writing).

This is the type of talented person that sits unknown in an office in a traditional publishing house… helping to create magic. I could rattle off a dozen or more names off the top of my head of similar people who make this happen every day. And that does not include the number of freelancers who are hired by publishers to take up the slack when they cannot meet the demands of the editing process in-house.

A critic might say, “But I can just hire these freelance people myself. Why do I need a traditional publisher?” That is a good point. But it misses a critical part of the process. It is illustrated by the question, “Who pays the invoice?”

Think about it for a moment. In a traditional publishing house the publisher is basically in charge. If there is a major dispute over editorial changes or input, the publisher has final say and contractual clout. Rarely is this used as a hammer, but the writer always knows it is there. In almost every case there are long discussions and a compromise is achieved.

But when the author hires the editor, who is the boss? The writer is the boss. The writer will usually defer to an editor’s comments. But what if your novel is going down a terrible path, a path to commercial destruction? I know of a case where an author was bent on writing a particular storyline and would not take anyone’s advice. His agent was unsuccessful. His writing friends and critique partners could not sway him from the path. If he were self-publishing he would have failed miserably. Instead an editor at a traditional publishing house recognized the talent and came alongside with valuable suggestions. The author, realizing that the editor had the goal of creating a great book, acceded to the advice. The book was saved, is now in print, and being sold in stores everywhere.

I also know of another case where a freelance editor took an author’s manuscript (to be self-published) and rearranged the non-fiction content from a topical presentation to a chronological presentation. (The book was the history of a specialized type of job in our court system.) The editor felt that a history should be told chronologically instead of topically. The author disagreed and made the editor put it all back the way it was in the first draft. Because the author was “paying the invoice” the author’s wishes prevailed. The book did not sell and was not adopted as a textbook, which was the goal of the author.

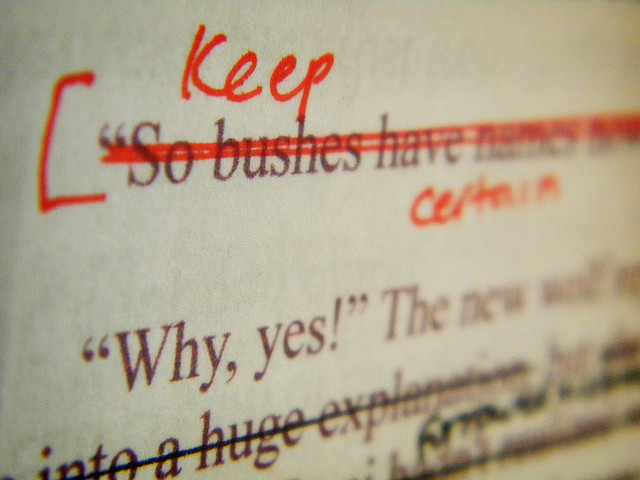

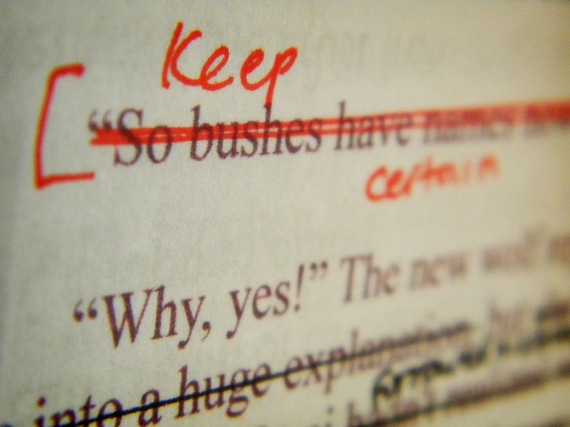

James Michener once said, “I’m not a good writer; I’ve been a masterful re-writer.” He has a fascinating book called James A. Michener’s Writer’s Handbook (1992). In this work are reproductions of the interaction between Michener and his editor. You can see the original text, the editorial suggestions, and the rewrite. A interesting exchange that is rarely seen.

As with the idea of “curation” I believe the editorial or content development process is a vital part of what a traditional publisher does for an author’s work.