A common experience for every literary agent and publisher is having a conversation with an author who would like a book published “as soon as possible.”

Frankly, it is for this purpose the author-services publishing industry was established, because of all the things that characterize traditional publishing, speed is not among them.

Traditional publishers have a certain number of books they want to publish each year, and the schedule fills up quickly.

One editor recently wrote me that they had 90 proposals on their desk to review, mostly from agents and existing relationships. This editor is personally responsible to acquire a dozen or so books per year. Their schedule could easily fill up for years to come. As a matter of fact, a number of academic publishers acquire titles five or more years into the future.

For most books, it takes 18-24 months from signing a contract to publishing it, not because a traditional publisher can’t get a book done quicker, but they already maxed out their capacity.

That’s one side of the equation. Now let’s focus on the author side.

What’s the hurry?

Since agents and publishers view writing as a profession, it would be best if authors defined their work the same way. Few professions think highly of someone in a hurry or reward impatience. Almost always, we skip steps we will regret later on.

Trust me on this one, I’ve done it myself.

Every agent and publisher requires “Platform first, book second.” But most authors attempt to skip the platform step. And platform is not only social media and promotion. It’s all the foundation-building that must be done in order to build a successful publishing career.

Maybe some professional people go through the steps quicker than others; but educators still need to do the academic work, doctors and musicians study and practice. Years may pass in the process.

Successful authors put in the time to learn, practice, write, then write some more, accept criticism, practice more, and write more.

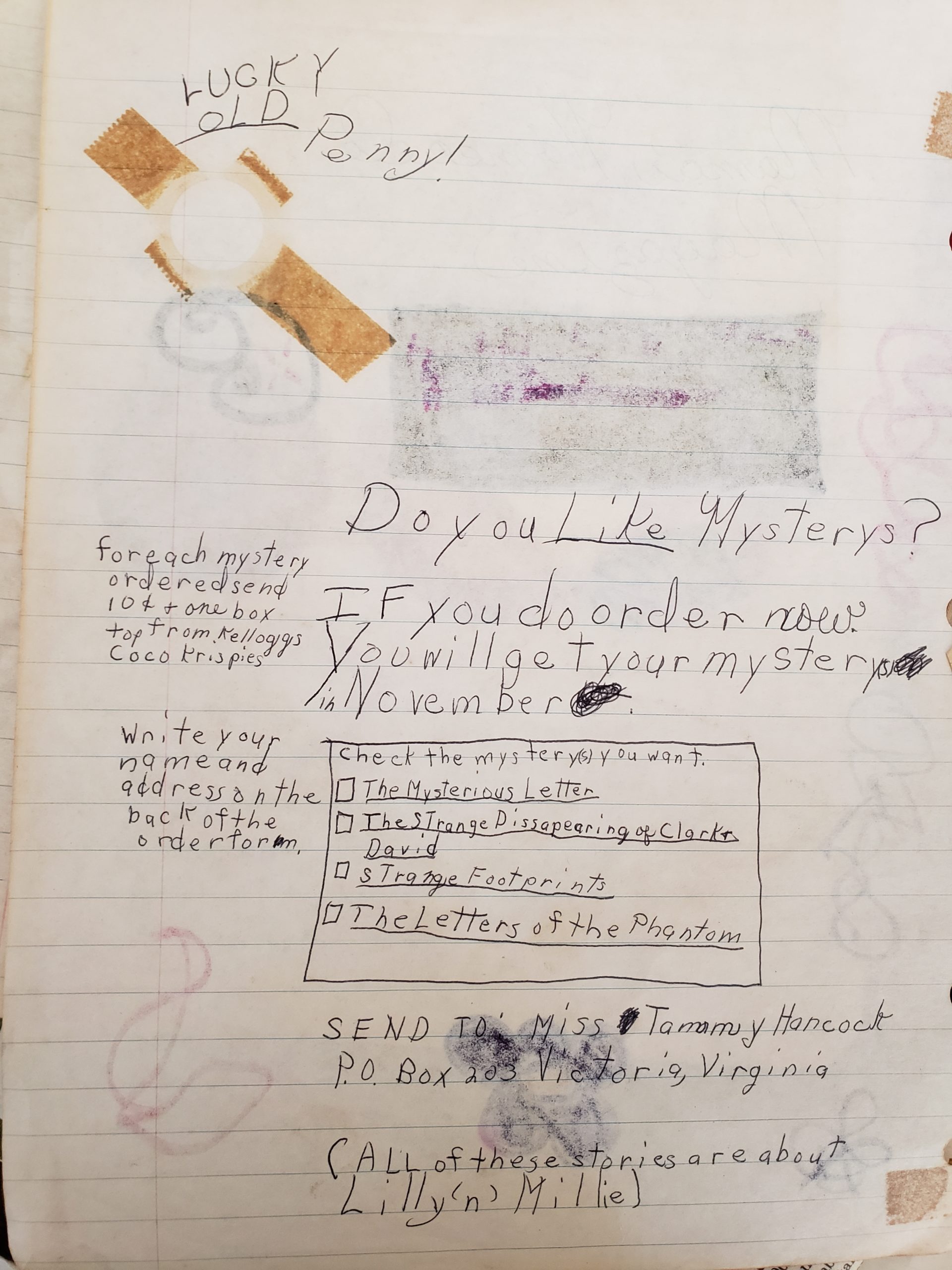

For authors of Christian books, I would suppose the urgency is the message in the book that needs to get out.

What is stopping you from communicating the message of the book?

Do you speak about the topic of your book? Have you written articles? Is the central message of your book part of your life and personal ministry?

Honestly, if the message of your desired book can be covered in a 1,500-word article or thirty-minute talk, why hold it back to appear in a book in two years?

This is why agents want to know what your subsequent titles will be. Agents work with those who desire to communicate through writing over a long period of time through many titles.

But if all you want is to get your book published, there are quicker ways to do that, which don’t test your patience or commitment.