It’s always struck me as a bit odd that the Rodgers and Hammerstein song from The Sound of Music, “My Favorite Things,” is considered by many to be a Christmas song. I suppose it’s related to the reference to “brown paper packages tied up with string.” Or maybe the sleighbells or snowflakes the song mentions. Sure, okay.

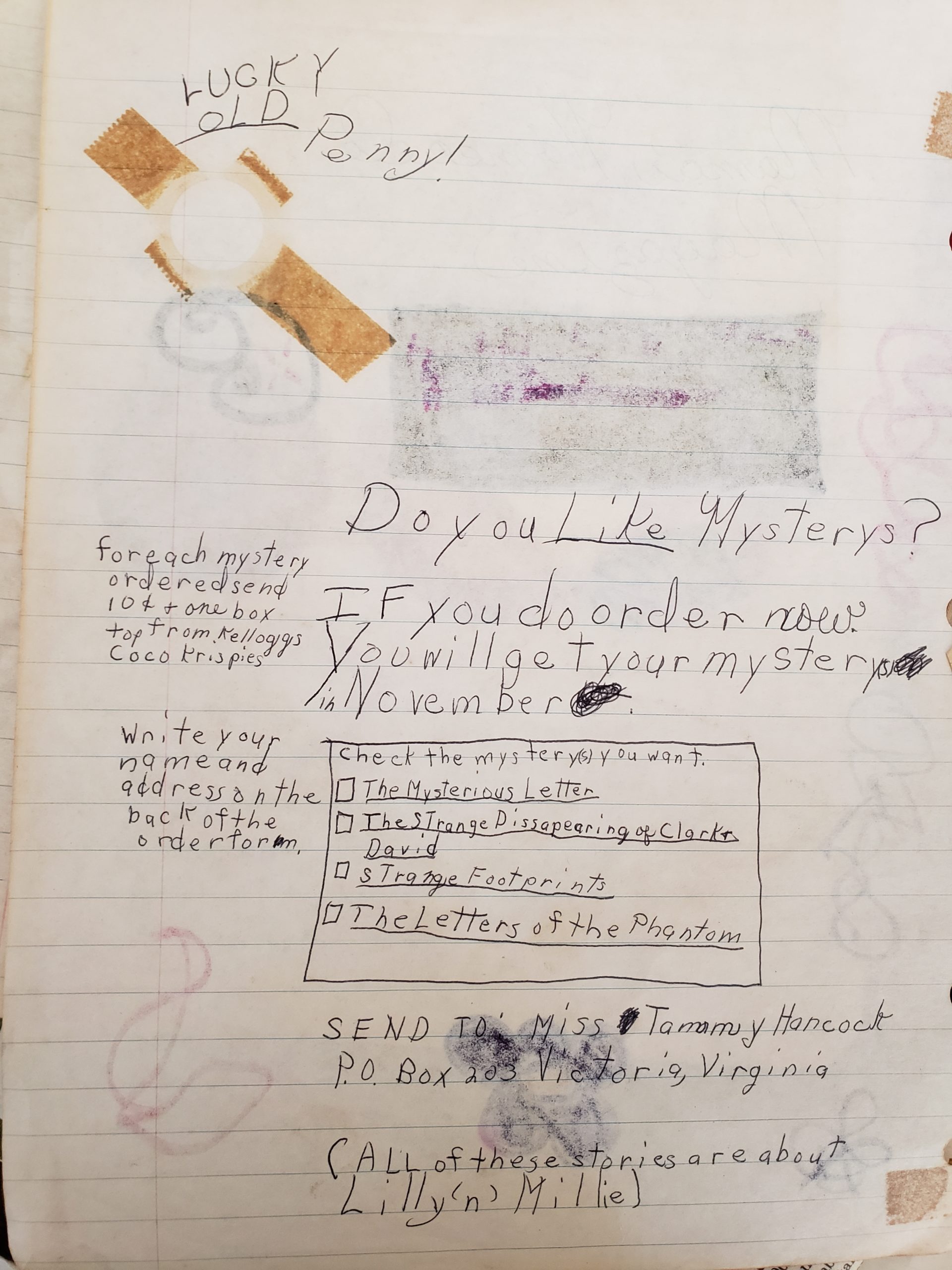

But as Christmas approaches this year, I thought I’d list a few of “my favorite things” I’ve received over the years—specifically, gifts that delighted this writer. Because, who knows, maybe there’s a writer on your Christmas list. Or perhaps, if you print this blog post and leave it somewhere conspicuous, someone might see it, take the hint, and buy you one of the following:

1. A leather-bound classic

I own a collection of classic books, many of which were given to me by my wife and children. Some are Franklin Library or Easton Press bindings; others are much older, such as the twenty-four-volume set of Sir Walter Scott’s Waverly novels a friend gave me.

2. An elegant fountain pen

I also have a small collection of fountain pens, and my favorite was a Christmas gift. There’s nothing quite like writing with a quality fountain pen.

3. Writing- and book-related Christmas ornaments

From our first Christmases together, my wife and I have made or bought a new ornament for each member of the household every year. So, decorating the tree is a beautiful, nostalgic experience—and many of “my” ornaments reflect my life as a writer.

4. A new journal

Since Christmas comes so close to the beginning of a new year, my loved ones (who know that I keep a journal) have several times given me a new, fresh journal as a Christmas gift. My favorites have been leather-bound journals from the gift shop at The Abbey of Gethsemani, where I’ve often enjoyed a silent prayer retreat.

5. A theater subscription

Since I’m not only a writer but also a Shakespeare nut, I was thrilled on several occasions to receive a season subscription to the Cincinnati Shakespeare Company. It was always a literary and theatrical delight.

6. A rubber stamp

A coworker, knowing my bibliophile tendencies (and compulsions), once gave me a “From the Library of Bob Hostetler” stamp and inkpad for my books. He even spelled my name right.

7. A mug

Have I mentioned that I’m a Shakespeare nut? I must do that often, as one of my fellow writers once gave me a “Shakespeare insults” mug. It’s a morning coffee favorite to this day.

What about you? What perfect-for-a-writer Christmas gifts have you received (or given) over the years? Please mention your favorites in the comments, for the benefit of all. And Merry Christmas!