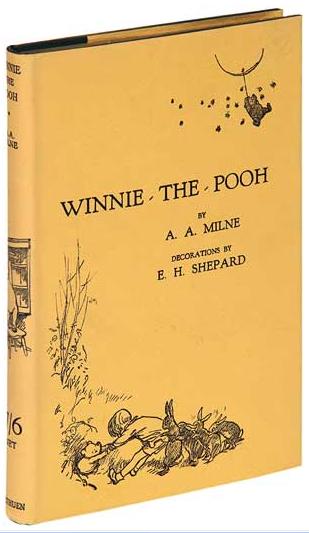

Winnie-the-Pooh turned 91 years old today, Saturday, October 14, 2017!

The book, Winnie-the-Pooh by A.A. Milne, was first published on October 14, 1926. Our family celebrates the day each year. Even with our kids all grown up and married, my wife still bakes Pooh cookies and decorates them.

Here are some fun publishing related facts about Winnie-the-Pooh:

- ‘Winnie-the-Pooh’ was published by Methuen Publishing, based in the UK, on October 14th, 1926. There were two sequels, Now We are Six in 1927, and The House at Pooh Corner in 1928.

- When We Were Very Young was an earlier book of children’s poetry published in 1924. The 38th poem in the book “Teddy Bear” is the first appearance of the Winnie-the Pooh character (called “Edward the Bear”).

- The books were acquired by editor E.V. Lucas who also signed Kenneth Graham (Wind in the Willows).

- The publisher (Methuen Publishing) was mostly known for their non-fiction, including Albert Einstein’s Relativity, the Special and the General Theory: A Popular Exposition published in 1920.

- The Pooh franchise is worth more than three billion dollars in annual revenue for Disney. Exceeding that of Mickey Mouse. In the Disney universe, it is the third largest franchise after “Disney Princess” and “Star Wars.”

- Winnie Ille Pu, a Latin translation of the original book, is the only Latin language book to ever be on the New York Times bestseller list. Released in December 1960 it remained on the Times list for 20 weeks and sold 125,000 copies in 21 printings during that time.

- Philosophy and Theology have attempted to plumb the depths of the Pooh universe. The Tao of Pooh and The Te of Pilglet as well as Pooh and the Philosophers: In Which it is Shown that All of Western Philosophy is Merely a Preamble to Winnie-the-Pooh have all been published. In addition is an online article asking “Was Winnie-the-Pooh a Good Muslim?” And if you want Christian Gospel related material do a search for “Gospel According to Pooh.” (The variety is intriguing. Southern Baptists, Congregationalists, a Scottish voice on a YouTube video, a Lenten course, and much more…)

- There is an online “wiki” online community called the Winniepedia with over 1,400 articles of things Pooh related. (The photo of the first edition above is found on their web site.)

- The Harbour Bookshop was opened in Devon, England in 1951 by Christopher Robin Milne, the son of A.A. Milne. He ran the store until 1983 when he retired. It closed in 2011.

- A signed, limited edition, set of the four hardcovers, as of the writing of this post, can be had for only £45,000 at this site in the UK. This set is signed by both A.A. Milne and Ernest Shepard, the illustrator.

This past week, in the United States, a PG-rated literary biopic movie Goodbye Christopher Robin was given a limited release in select cities. It has received very mixed reviews since the film ultimately explores the unhappiness of the son, Christopher Robin Milne, depicted in the beloved stories (at least 40 reviews of the movie can be found on this imdb.com site).